Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

For use at 11:00 a.m. EST

March 1, 2024

Monetary Policy rePort

March 1, 2024

Letter of transmittaL

B G

F R S

Washington, D.C., March 1, 2024

T P S

T S H R

The Board of Governors is pleased to submit its Monetary Policy Report pursuant to

section 2B of the Federal Reserve Act.

Sincerely,

Jerome H. Powell, Chair

statement on Longer-run goaLs and monetary PoLicy strategy

Adopted effective January24, 2012; as reafrmed effective January30, 2024

The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) is rmly committed to fullling its statutory mandate from

the Congress of promoting maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates. The

Committee seeks to explain its monetary policy decisions to the public as clearly as possible. Such clarity

facilitates well-informed decisionmaking by households and businesses, reduces economic and nancial

uncertainty, increases the eectiveness of monetary policy, and enhances transparency and accountability,

which are essential in a democratic society.

Employment, ination, and long-term interest rates uctuate over time in response to economic and nancial

disturbances. Monetary policy plays an important role in stabilizing the economy in response to these

disturbances. The Committee’s primary means of adjusting the stance of monetary policy is through changes

in the target range for the federal funds rate. The Committee judges that the level of the federal funds rate

consistent with maximum employment and price stability over the longer run has declined relative to its

historical average. Therefore, the federal funds rate is likely to be constrained by its eective lower bound

more frequently than in the past. Owing in part to the proximity of interest rates to the eective lower bound,

the Committee judges that downward risks to employment and ination have increased. The Committee is

prepared to use its full range of tools to achieve its maximum employment and price stability goals.

The maximum level of employment is a broad-based and inclusive goal that is not directly measurable

and changes over time owing largely to nonmonetary factors that aect the structure and dynamics of the

labor market. Consequently, it would not be appropriate to specify a xed goal for employment; rather, the

Committee’s policy decisions must be informed by assessments of the shortfalls of employment from its

maximum level, recognizing that such assessments are necessarily uncertain and subject to revision. The

Committee considers a wide range of indicators in making these assessments.

The ination rate over the longer run is primarily determined by monetary policy, and hence the Committee

has the ability to specify a longer-run goal for ination. The Committee rearms its judgment that ination

at the rate of 2percent, as measured by the annual change in the price index for personal consumption

expenditures, is most consistent over the longer run with the Federal Reserve’s statutory mandate. The

Committee judges that longer-term ination expectations that are well anchored at 2percent foster price

stability and moderate long-term interest rates and enhance the Committee’s ability to promote maximum

employment in the face of signicant economic disturbances. In order to anchor longer-term ination

expectations at this level, the Committee seeks to achieve ination that averages 2percent over time, and

therefore judges that, following periods when ination has been running persistently below 2percent,

appropriate monetary policy will likely aim to achieve ination moderately above 2percent for some time.

Monetary policy actions tend to inuence economic activity, employment, and prices with a lag. In setting

monetary policy, the Committee seeks over time to mitigate shortfalls of employment from the Committee’s

assessment of its maximum level and deviations of ination from its longer-run goal. Moreover, sustainably

achieving maximum employment and price stability depends on a stable nancial system. Therefore, the

Committee’s policy decisions reect its longer-run goals, its medium-term outlook, and its assessments of

the balance of risks, including risks to the nancial system that could impede the attainment of the

Committee’s goals.

The Committee’s employment and ination objectives are generally complementary. However, under

circumstances in which the Committee judges that the objectives are not complementary, it takes into account

the employment shortfalls and ination deviations and the potentially dierent time horizons over which

employment and ination are projected to return to levels judged consistent with its mandate.

The Committee intends to review these principles and to make adjustments as appropriate at its annual

organizational meeting each January, and to undertake roughly every 5years a thorough public review of its

monetary policy strategy, tools, and communication practices.

contents

Note: This report reects information that was publicly available as of noon EST on February29, 2024.

Unless otherwise stated, the time series in the gures extend through, for daily data, February27, 2024; for monthly

data, January2024; and, for quarterly data, 2023:Q4. In bar charts, except as noted, the change for a given period is

measured to its nal quarter from the nal quarter of the preceding period.

For gures 33 and 40 as well as gure C in the box “Recent Housing Market Developments,” note that the S&P/Case-Shiller U.S. National Home Price

Index, the S&P 500 Index, and the Dow Jones Bank Index are products of S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC and/or its afliates and have been licensed for use

by the Board. Copyright © 2024 S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC, a division of S&P Global, and/or its afliates. All rights reserved. Redistribution, reproduction,

and/or photocopying in whole or in part are prohibited without written permission of S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC. For more information on any of S&P

Dow Jones Indices LLC’s indices, please visit www.spdji.com. S&P® is a registered trademark of Standard & Poor’s Financial Services LLC, and Dow Jones®

is a registered trademark of Dow Jones Trademark Holdings LLC. Neither S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC, Dow Jones Trademark Holdings LLC, their afliates,

nor their third-party licensors make any representation or warranty, express or implied, as to the ability of any index to accurately represent the asset class

or market sector that it purports to represent, and neither S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC, Dow Jones Trademark Holdings LLC, their afliates, nor their third-

party licensors shall have any liability for any errors, omissions, or interruptions of any index or the data included therein.

contents

Summary .................................................................1

Recent Economic and Financial Developments ................................... 1

Monetary Policy ........................................................... 2

Special Topics ............................................................. 3

Part 1: Recent Economic and Financial Developments .....................5

Domestic Developments. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5

Financial Developments .................................................... 24

International Developments ................................................. 30

Part 2: Monetary Policy ..................................................35

Part 3: Summary of Economic Projections ................................45

Abbreviations ............................................................63

List of Boxes

Employment and Earnings across Demographic Groups ............................ 10

Recent Housing Market Developments ......................................... 19

Developments Related to Financial Stability ..................................... 27

Developments in the Federal Reserve’s Balance Sheet and Money Markets .............. 38

Monetary Policy Rules in the Current Environment ................................ 41

Forecast Uncertainty ....................................................... 60

1

While ination remains above the Federal

Open Market Committee’s (FOMC) objective

of 2percent, it has eased substantially over

the past year, and the slowing in ination

has occurred without a signicant increase

in unemployment. The labor market remains

relatively tight, with the unemployment rate

near historically low levels and job vacancies

still elevated. Real gross domestic product

(GDP) growth has also been strong, supported

by solid increases in consumer spending.

The FOMC has maintained the target range

for the federal funds rate at 5¼ to 5½percent

since its July2023 meeting. The Committee

views the policy rate as likely at its peak for

this tightening cycle, which began in early

2022. The Federal Reserve has also continued

to reduce its holdings of Treasury and agency

mortgage-backed securities.

As labor market tightness has eased and

progress on ination has continued, the risks

to achieving the Committee’s employment and

ination goals have been moving into better

balance. Even so, the Committee remains

highly attentive to ination risks and is acutely

aware that high ination imposes signicant

hardship, especially on those least able to meet

the higher costs of essentials.

The FOMC is strongly committed to

returning ination to its 2percent objective.

In considering any adjustments to the target

range for the federal funds rate, the Committee

will carefully assess incoming data, the

evolving outlook, and the balance of risks.

The Committee does not expect it will be

appropriate to reduce the target range until it

has gained greater condence that ination is

moving sustainably toward 2percent.

Recent Economic and Financial

Developments

Ination. Consumer price ination has

slowed notably but remains above 2percent.

The price index for personal consumption

expenditures (PCE) rose 2.4percent over the

12months ending in January, down from a

peak of 7.1percent in 2022. The core PCE

price index—which excludes volatile food

and energy prices and is generally considered

a better guide to the direction of future

ination—rose 2.8percent in the 12months

ending in January, and the slowing in ination

was widespread across both goods and

services prices. More recently, core PCE prices

increased at an annual rate of 2.5percent over

the sixmonths ending in January, though

measuring ination over relatively short

periods risks exaggerating the inuence of

idiosyncratic or temporary factors. Measures

of longer-term ination expectations are

within the range of values seen in the decade

before the pandemic and continue to be

broadly consistent with the FOMC’s longer-

run objective of 2percent.

The labor market. The labor market has

remained relatively tight, with job gains

averaging 239,000 per month since June

and the unemployment rate near historical

lows. Labor demand has eased—as job

openings have declined in many sectors of the

economy—but continues to exceed the supply

of available workers. Labor supply has trended

higher over the past year, reecting a continued

strong pace of immigration and increases in

the labor force participation rate, particularly

among prime-age workers. Reecting the

improved balance between labor demand and

supply, nominal wage gains slowed in 2023,

but they remain above a pace consistent with

2percent ination over the longer term, given

prevailing trends in productivity growth.

Economic activity. Real GDP increased

3.1percent last year, notably faster than in

2022 despite tighter nancial conditions,

including elevated longer-term interest rates.

Consumer spending grew at a solid pace,

and housing market activity started to turn

back up in the second half of last year after

summary

2 SUMMARY

having declined since early 2021. However,

real business xed investment growth slowed,

likely reecting tighter nancial conditions and

downbeat business sentiment. In contrast to

GDP, manufacturing output was little changed,

on net, last year, a downshift following two

years of robust post-pandemic gains.

Financial conditions. Conditions in nancial

markets tightened considerably further over the

summer and early fall before reversing course

toward the end of the year. The FOMC raised

the target range for the federal funds rate a

further 25 basis points at its meeting last July,

bringing the overall increase in the target range

for this tightening cycle to 525 basis points.

The market-implied expected path of the

federal funds rate has moved up, on net, since

the middle of 2023, and yields on longer-term

nominal Treasury securities are notably higher

on balance. Credit remains generally available

to most households and businesses but at

elevated interest rates, which have weighed

on nancing activity. Lending by banks to

households and businesses slowed notably

since June as banks continued to tighten

standards and demand for loans softened.

Financial stability. Overall, the banking system

remains sound and resilient; although acute

stress in the banking system has receded

since last March, a few areas of risk warrant

continued monitoring. Upward pressure on

asset valuations continued, with real estate

prices elevated relative to rents and high

price-to-earnings ratios in equity markets.

Borrowing from nonnancial businesses

and households continued to increase at a

pace slower than that of nominal GDP, and

the combined debt-to-GDP ratio now sits

close to its 20-year low. Vulnerabilities from

nancial-sector leverage remain notable. While

risk-based bank capital ratios stayed solid

and increased broadly, declines in the fair

values of xed-rate assets have been sizable

relative to the regulatory capital at some

banks. Meanwhile, leverage at hedge funds

has stabilized at high levels, and leverage

at life insurers increased to values close to

the historical averages but with a liability

composition that has become more reliant

on nontraditional sources of funding. Most

banks maintained high liquidity and stable

funding, while bank funding costs continue to

increase. (See the box “Developments Related

to Financial Stability” in Part 1.)

International developments. Following a

rebound in early 2023, growth in foreign

economic activity was subdued in the

second half of last year. Economic growth

was particularly weak in advanced foreign

economies (AFEs) as monetary policy

tightening weighed on activity and high

ination eroded real household incomes.

Structural adjustment to higher energy prices

in Europe continued to hinder economic

performance, while property-sector weakness

and sluggish domestic demand restrained

Chinese economic activity. Foreign headline

ination has fallen further, reecting declines

in core and food ination. However, the pace

of disination has varied across countries and

sectors, with the moderation in goods ination

generally outpacing that in services ination.

Most foreign central banks paused policy

interest rate hikes in the second half of last

year and have since held rates steady. Policy

rate paths implied by nancial market pricing

suggest that central banks in many AFEs are

expected to begin lowering their policy rates

in 2024. Several central banks in emerging

market economies have already begun easing

monetary policy. The trade-weighted exchange

value of the U.S. dollar has increased slightly,

on net, since the middle of last year.

Monetary Policy

Interest rate policy. After signicantly

tightening the stance of monetary policy

since early 2022, the FOMC has maintained

the target range for the policy rate at 5¼to

5½percent since its meeting last July.

Although the FOMC judges that the risks to

achieving its employment and ination goals

are moving into better balance, the Committee

MONETARY POLICY REPORT: MARCH 2024 3

remains highly attentive to ination risks.

The Committee has indicated that it does

not expect it will be appropriate to reduce

the target range until it has gained greater

condence that ination is moving sustainably

toward 2percent. In considering any

adjustments to the target range for the federal

funds rate, the Committee will carefully assess

incoming data, the evolving outlook, and the

balance of risks.

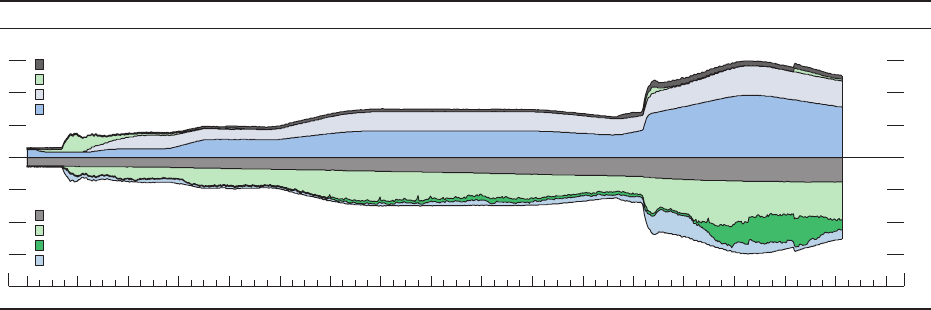

Balance sheet policy. The Federal Reserve has

continued the process of signicantly reducing

its holdings of Treasury and agency securities

in a predictable manner, contributing to the

tightening of nancial conditions.

1

Beginning

in June2022, principal payments from

securities held in the System Open Market

Account have been reinvested only to the

extent that they exceeded monthly caps. Under

this policy, the Federal Reserve has reduced

its securities holdings about $640billion since

mid-June2023, bringing the total reduction in

securities holdings since the start of balance

sheet runo to about $1.4trillion. The

FOMC has stated that it intends to maintain

securities holdings at amounts consistent with

implementing monetary policy eciently

and eectively in its ample-reserves regime.

To ensure a smooth transition, the FOMC

intends to slow and then stop reductions in

its securities holdings when reserve balances

are somewhat above the level that the FOMC

judges to be consistent with ample reserves.

Special Topics

Employment and earnings across groups. An

exceptionally tight labor market over the past

two years has been especially benecial for

historically disadvantaged groups of workers.

As a result, many of the long-standing

disparities in employment and wages by sex,

1. See the May4, 2022, press release regarding the

Plans for Reducing the Size of the Federal Reserve’s

Balance Sheet, available on the Board’s website at https://

www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/pressreleases/

monetary20220504b.htm.

race, ethnicity, and education have narrowed,

and some gaps reached historical lows in

2023. However, despite this narrowing,

signicant disparities in absolute levels across

groups remain. (See the box “Employment

and Earnings across Demographic Groups”

in Part 1.)

Housing sector. The rise in mortgage rates

over the past two years has reduced housing

demand, resulting in a steep drop in housing

activity in 2022 and a marked slowing in

house price growth from its historically high

pace. Osetting factors boosting housing

demand, such as the robust job market and

the increased prevalence of remote work,

have prevented signicant price declines.

High mortgage rates have also discouraged

some potential sellers with low rates on their

current mortgages from moving, which has

kept the existing home market unusually thin.

The shortage of available existing homes has

pushed some remaining homebuyers toward

new homes and supported a modest rebound

in construction of single-family homes later

in 2023. In contrast, multifamily starts rose

to historically high levels in 2022 but have

more recently fallen back because of builders’

concerns about the eect of the signicant

amount of new multifamily supply on rents

and property prices. (See the box “Recent

Housing Market Developments” in Part 1.)

Federal Reserve’s balance sheet and money

markets. The size of the Federal Reserve’s

balance sheet has decreased since June as

the FOMC continued to reduce its securities

holdings. Despite ongoing balance sheet

runo, reserve balances—the largest liability

on the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet—edged

up as declines in the usage of the overnight

reverse repurchase agreement facility—

another Federal Reserve liability—more

than matched the decline in assets. (See the

box “Developments in the Federal Reserve’s

Balance Sheet and Money Markets” in Part2.)

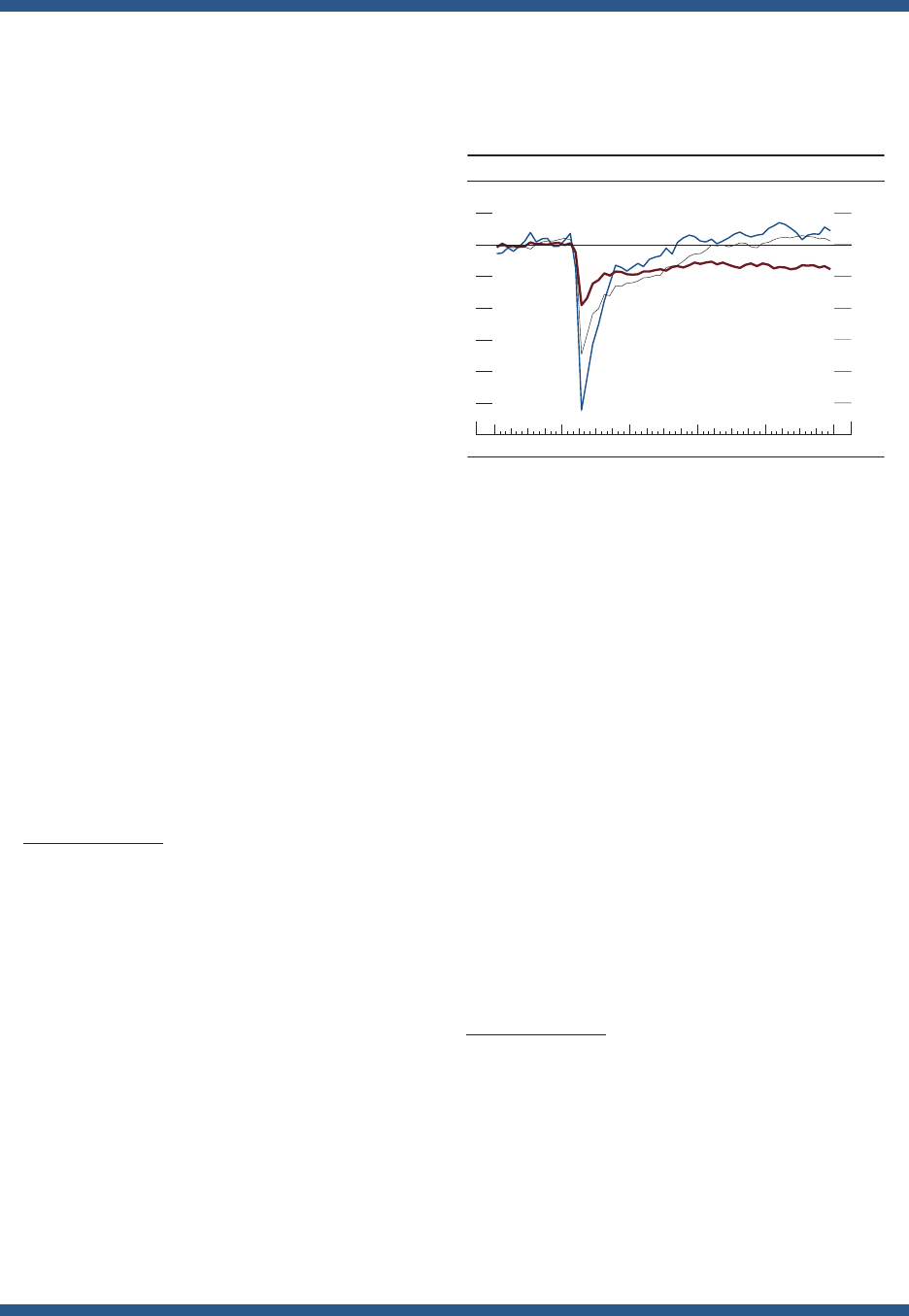

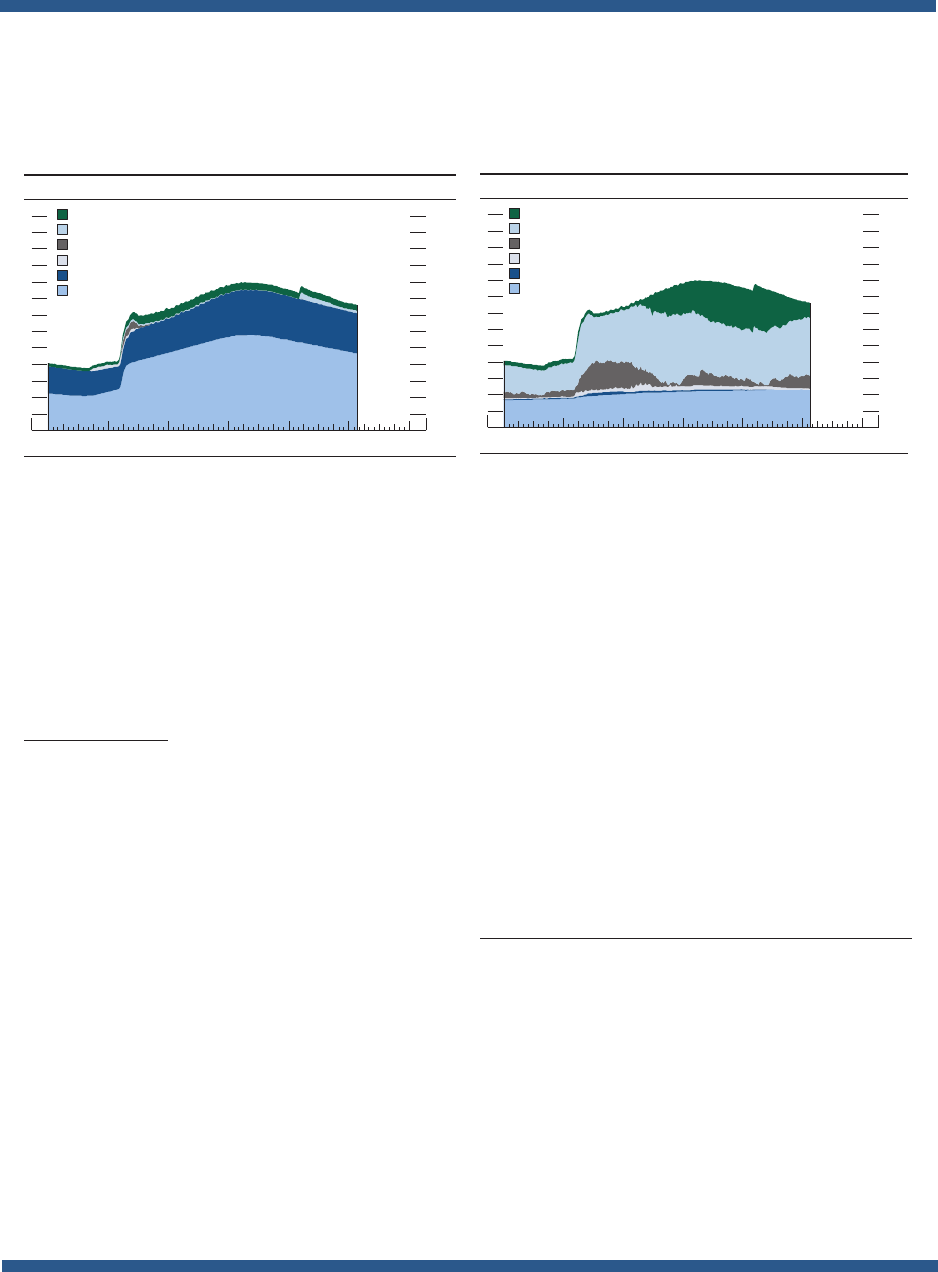

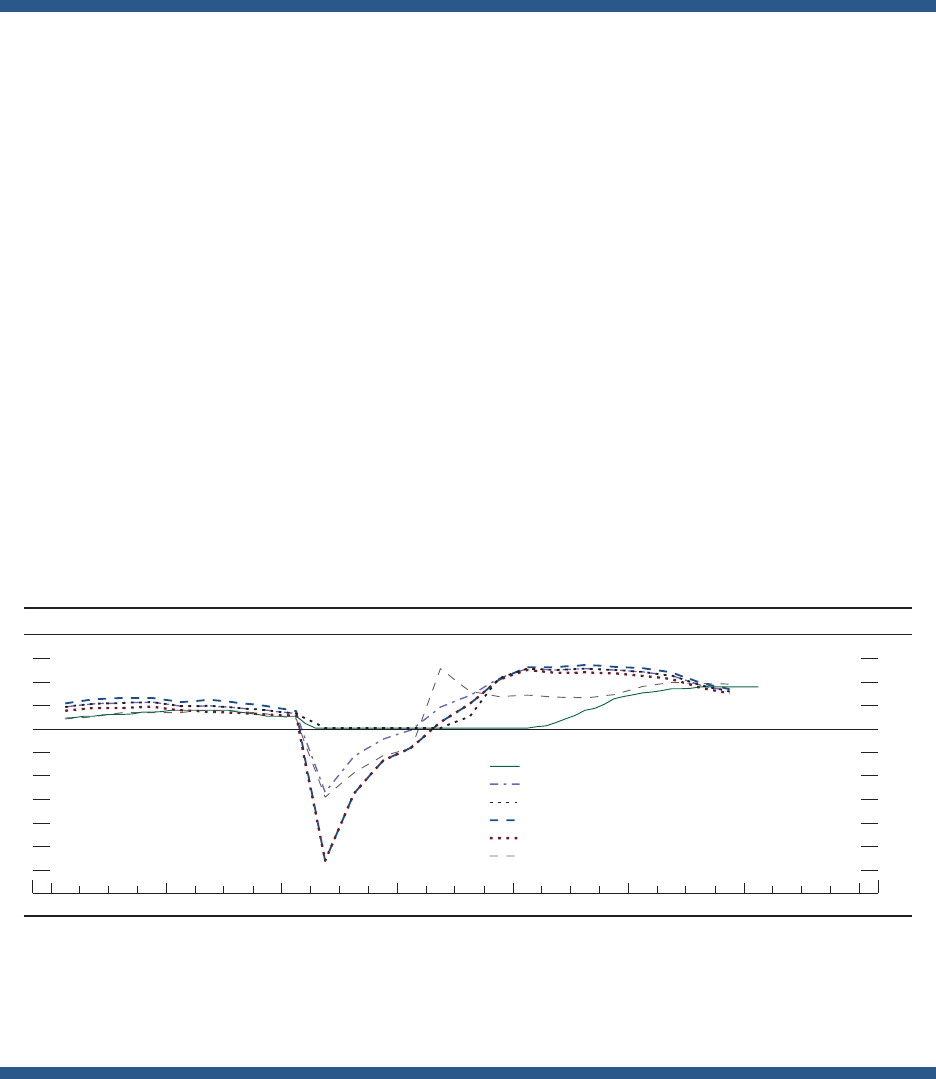

Monetary policy rules. Simple monetary policy

rules, which prescribe a setting for the policy

4 SUMMARY

interest rate in response to the behavior of

a small number of economic variables, can

provide useful guidance to policymakers.

With ination easing and supply and demand

conditions in labor markets coming into better

balance, the policy rate prescriptions of most

simple monetary policy rules have decreased

recently and now call for levels of the federal

funds rate that are close to the current target

range for the federal funds rate. (See the

box “Monetary Policy Rules in the Current

Environment” inPart2.)

5

Domestic Developments

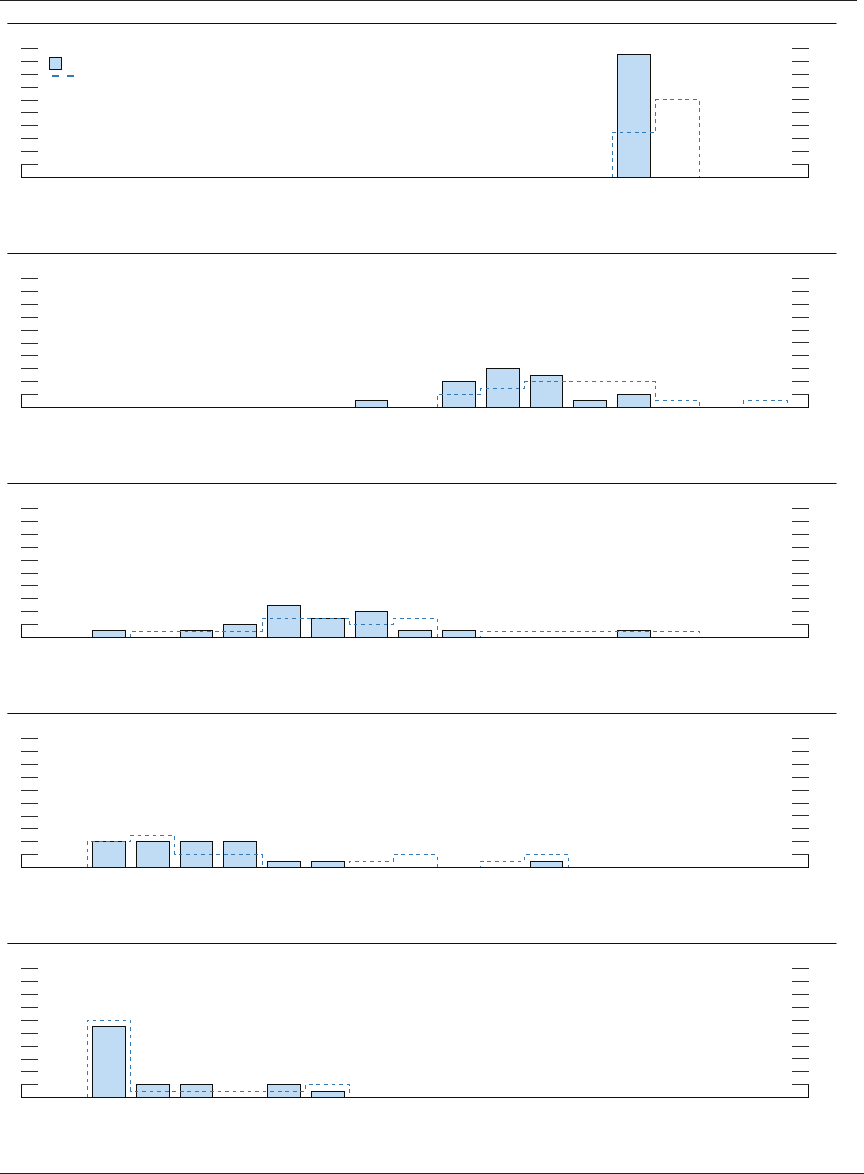

Ination has eased but remains elevated

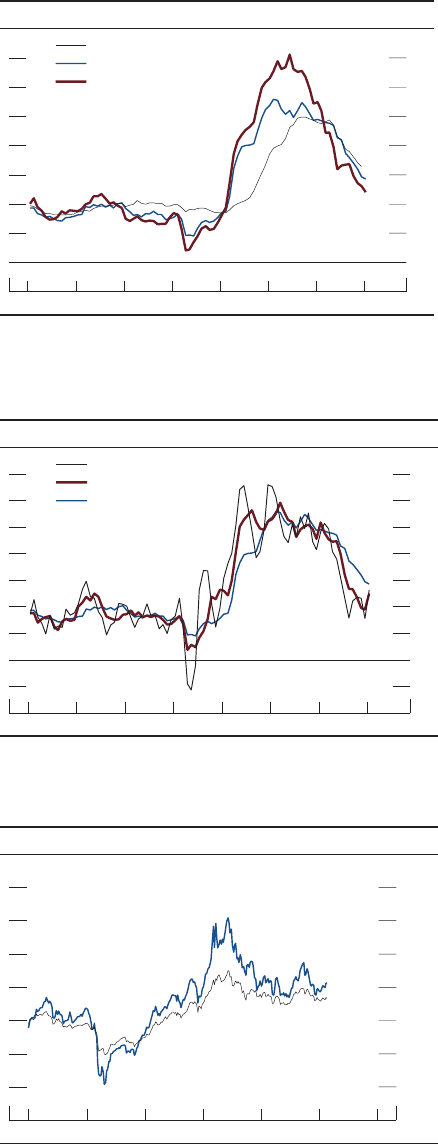

After surging in 2021 and 2022, ination

slowed notably last year. The price index for

personal consumption expenditures (PCE)

rose 2.4percent over the 12months ending

in January, down from a peak of 7.1percent

in 2022, though still above the Federal Open

Market Committee’s (FOMC) longer-run

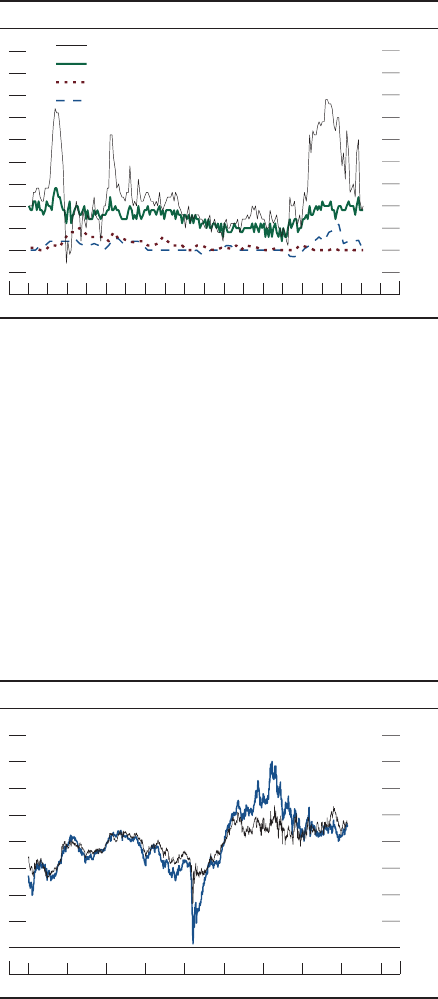

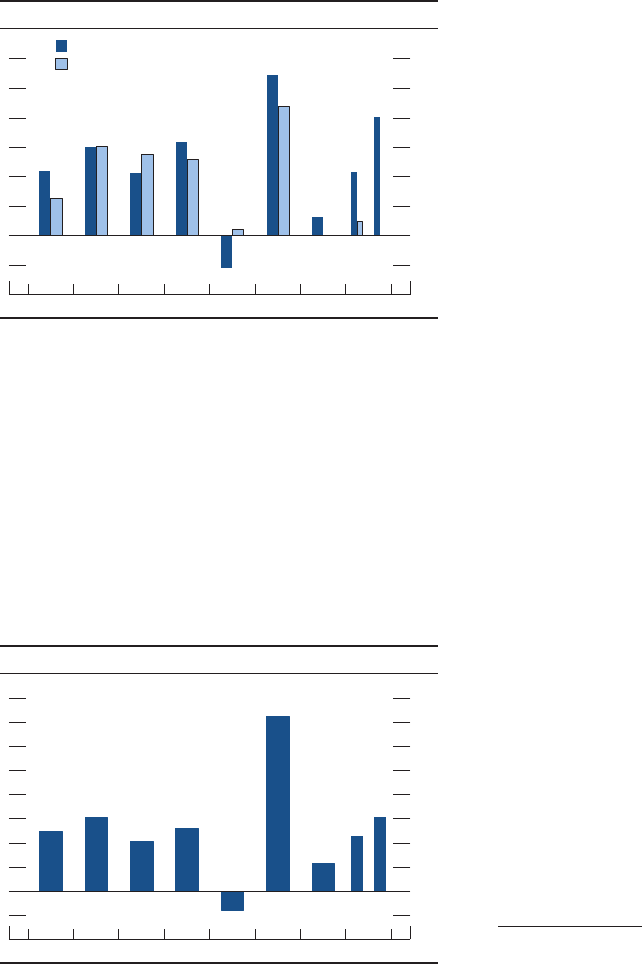

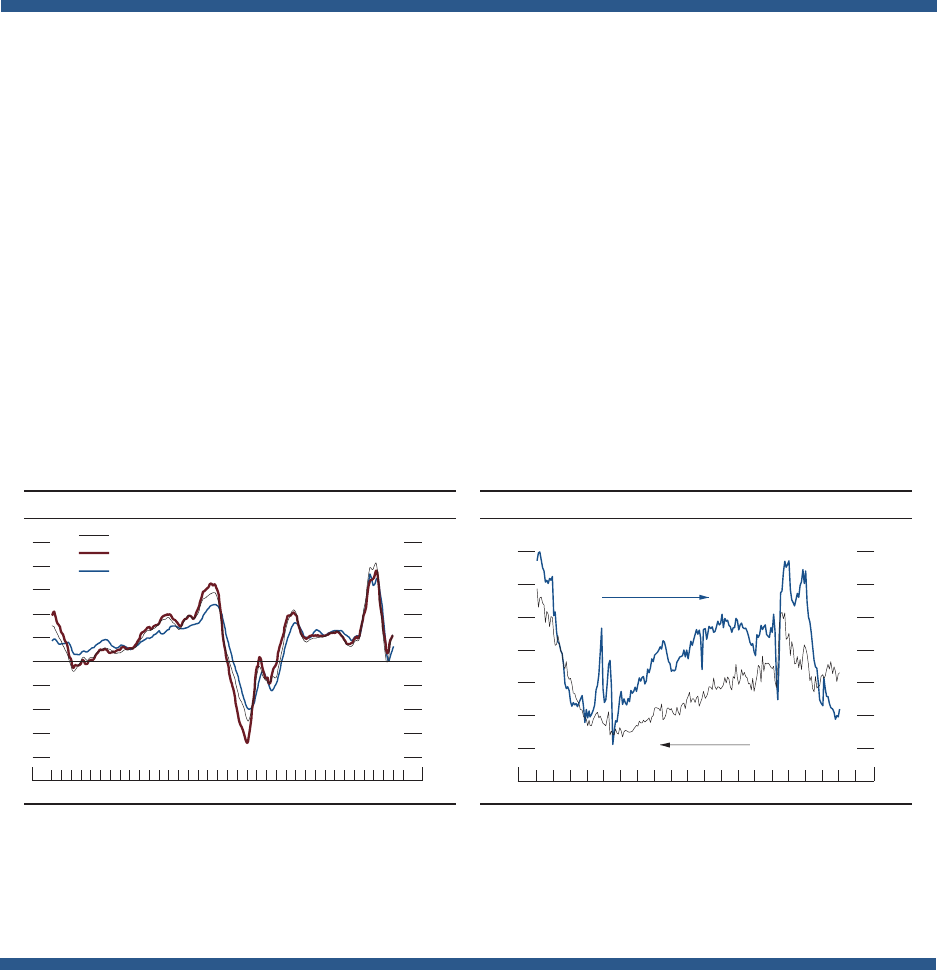

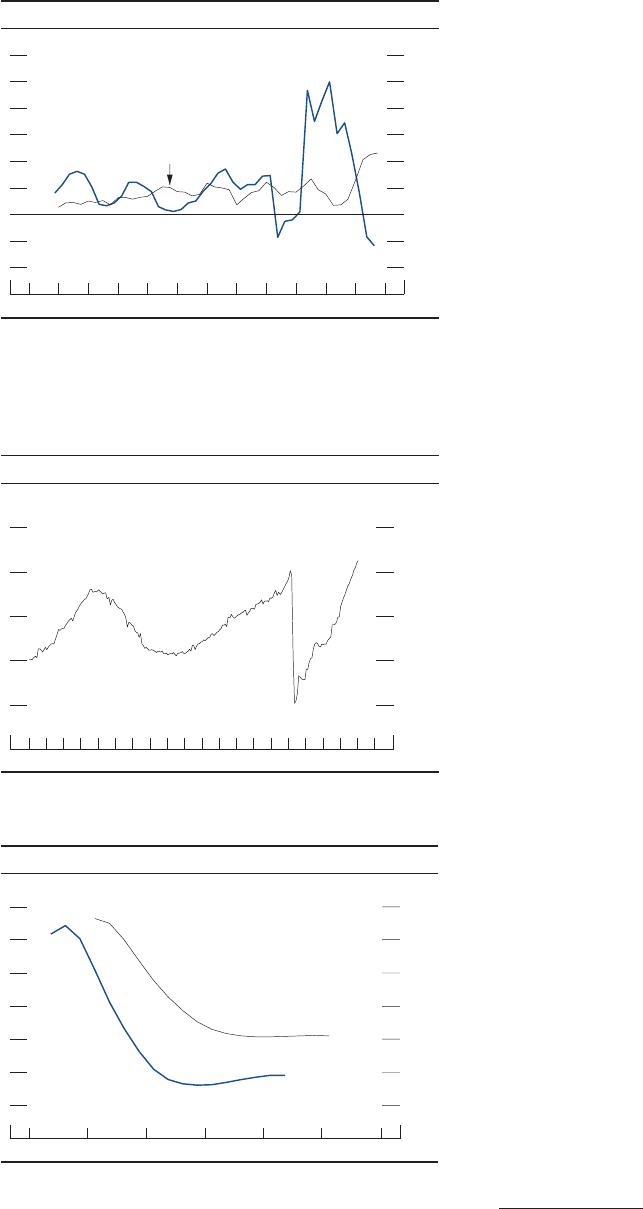

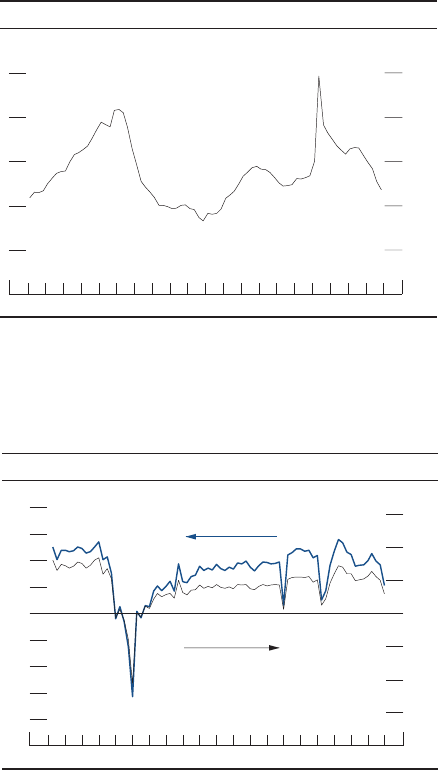

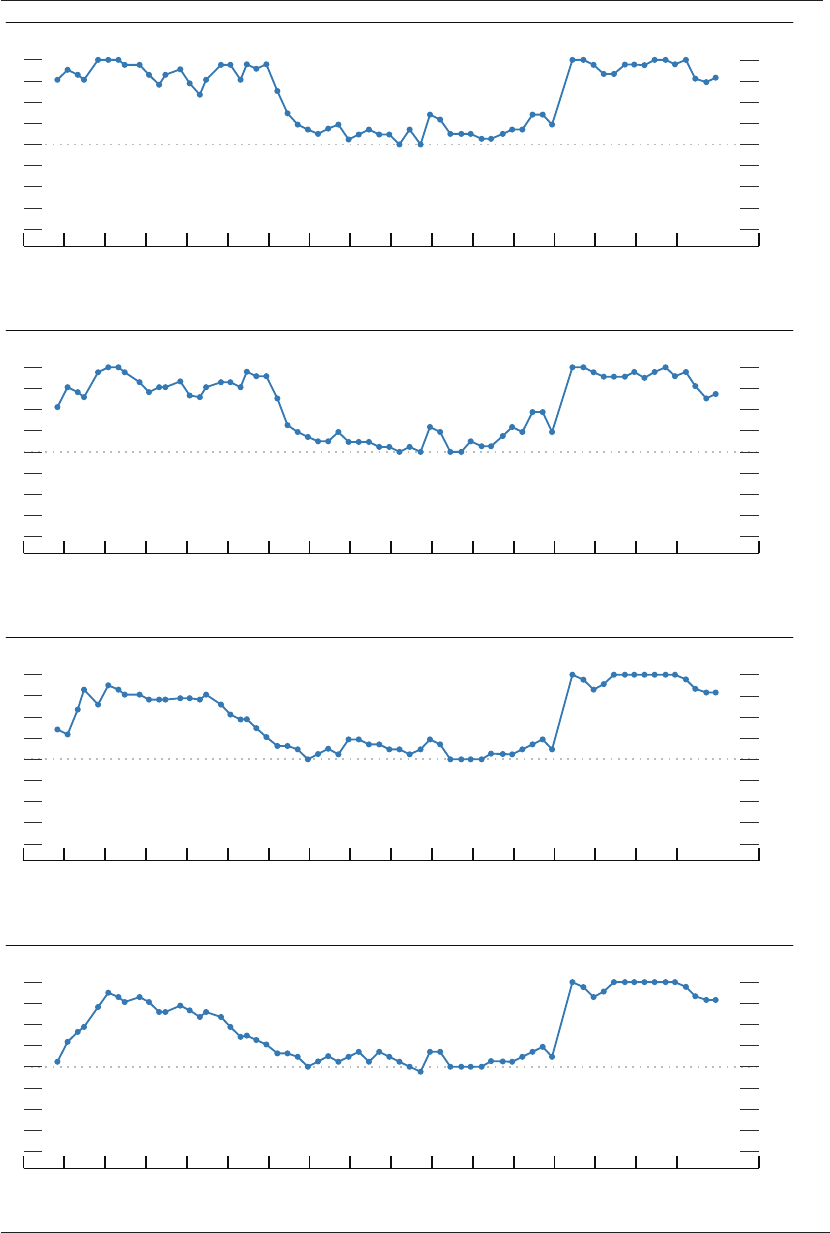

objective of 2percent (gure1). The core PCE

price index—which excludes volatile food

and energy prices—rose 2.8percent over the

12months ending in January. More recently,

core PCE prices increased at an annual rate

of 2.5percent over the six months ending

in January, though measuring ination over

relatively short periods risks exaggerating

the inuence of idiosyncratic or temporary

factors (gure2). The trimmed mean measure

of PCE prices constructed by the Federal

Reserve Bank of Dallas—which provides an

alternative approach to reducing the inuence

of idiosyncratic price movements—increased

3.3percent over the 12months ending

in December, somewhat higher than the

coreindex (gure 1).

Consumer energy prices have

declined, while food price ination has

slowedmarkedly

After hovering around $80 per barrel in the

rst half of last year, oil prices rose notably

in late summer, albeit to levels still well below

those seen in 2022, but have since declined,

on net, to around $83 per barrel (gure3).

Gasoline prices have followed a similar

pattern. The moderation in oil prices last

fall reects weak economic activity abroad

and increases in U.S. and other non-OPEC

(Organization of the Petroleum Exporting

Countries) oil production. Since late last year,

geopolitical tensions in the Middle East and

rerouting of shipping away from the Red Sea

have placed some upward pressure on oil

Part 1

recent economic and financiaL deveLoPments

Excluding food and energy

Total

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

Percent change from year earlier

20242023202220212020201920182017

1. Personal consumption expenditures price indexes

Monthly

N

OTE

: Trimmed mean data extend through December 2023.

S

OURCE

: For trimmed mean, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas; for a

ll

else, Bureau of Economic Analysis; all via Haver Analytics.

Trimmed mean

12-month change

6-month change

1

+

_

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

Percent, annual rate

20242023202220212020201920182017

2. Core personal consumption expenditure price index

Monthly

SOURCE: Bureau of Economic Analysis, personal consumption

expenditures via Haver Analytics.

3-month change

Brent spot price

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

Dollars per barrel

2019 2020 2021 2022 2023 2024

3. Spot and futures prices for crude oil

Weekly

24-month-ahead

futures contracts

N

OTE

: The data are weekly averages of daily data and extend throug

h

February 23, 2024.

S

OURCE

: ICE Brent Futures via Bloomberg.

6 PART 1: RECENT ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL DEVELOPMENTS

prices. Continuing geopolitical tensions pose

an upside risk to energy prices. Natural gas

prices remain well below the elevated 2022

levels due to strong production and high

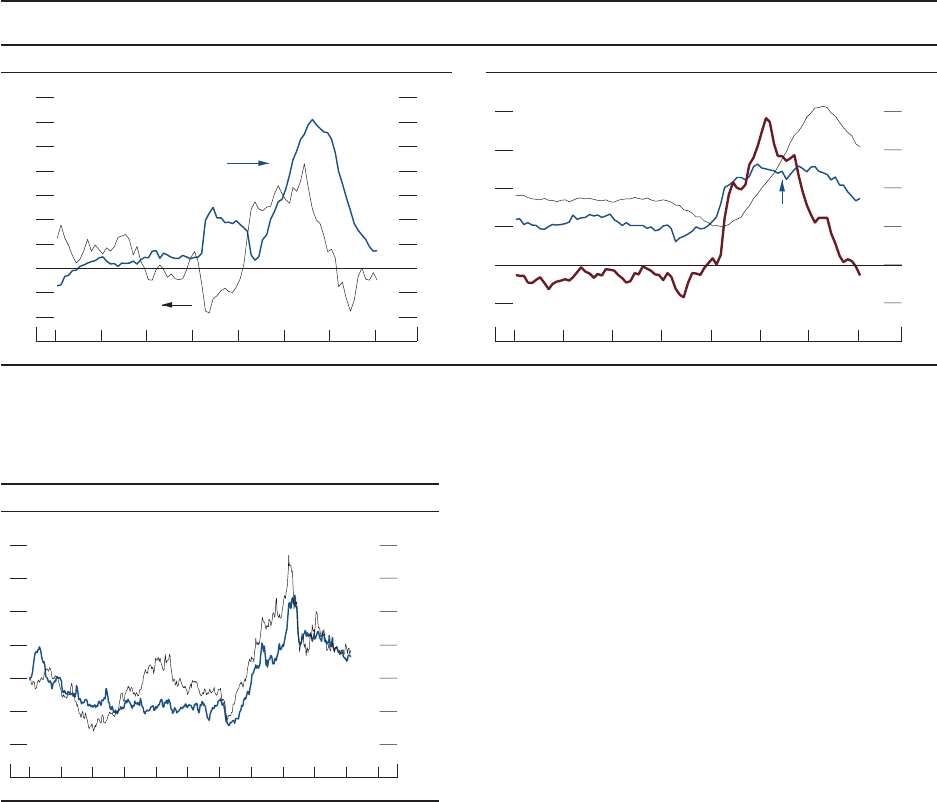

inventory levels. All told, consumer energy

prices fell 4.9percent in the 12months ending

in January (gure4, left panel).

Food price ination slowed markedly last

year, as prices of agricultural commodities

and livestock fell (gure5). This moderation

brought the 12-month change in food prices

down to 1.4percent in January, a substantial

slowing from the 11percent increase recorded

over 2022 (gure4, left panel).

Prices of both energy and food products are

of particular importance for lower-income

households, for which such necessities account

for a large share of expenditures. Reecting the

sharp increases seen in 2021 and 2022, these

price indexes are about 25percent higher than

before the pandemic.

Core goods prices have been declining as

supply bottlenecks ease and import price

ination falls . . .

Outside of food and energy prices, there has

been signicant deceleration across the main

spending categories, though disination

Food and

beverages

Services

ex. energy

and housing

Goods ex. food, beverages, and energy

20

10

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

4

2

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

Percent change from year earlier

20242023202220212020201920182017

Food and energy

Percent change from year earlier

Energy

+

–

+

–

2

+

_

0

2

4

6

8

Percent change from year earlier

20242023202220212020201920182017

Components of core prices

Monthly

Housing services

NOTE: The data are monthly.

SOURCE: Bureau of Economic Analysis via Haver Analytics.

4. Subcomponents of personal consumption expenditures price indexes

Agriculture

and livestock

60

80

100

120

140

160

180

Week ending January 3, 2014 = 100

2014 2016 2018 2020 2022 2024

5. Spot prices for commodities

Weekly

Industrial metals

N

OTE

: The data are weekly averages of daily data and extend through

February 23, 2024.

S

OURCE

: For industrial metals, S&P GSCI Industrial Metals Spot

Index; for agriculture and livestock, S&P GSCI Agriculture & Livestock

Spot Index; both via Haver Analytics.

MONETARY POLICY REPORT: MARCH 2024 7

has been more pronounced in some than in

others (gure4, right panel). Core goods

prices fell 0.6percent in the 12 months

ending in January, and the deceleration was

broad based, as the supply chain issues and

other capacity constraints that had earlier

boosted ination so much eased substantially.

For example, suppliers’ delivery times had

lengthened considerably during the pandemic

but have been getting shorter over the past

year (gure6). Core goods ination was also

held down last year by a net decline in nonfuel

import prices, which, in turn, largely reected

falling commodity prices (gure7).

. . . while core services price ination has

been slowing but remains elevated

Price ination for both housing services and

core services other than housing slowed over

the past year, though it remains elevated.

Increases in housing services prices began

to moderate, coming in at 6.1percent in the

12months ending in January, down from a

peak of more than 8percent (gure4, right

panel). This slowing is consistent with the

notably smaller increases in market rents on

new housing leases to new tenants seen since

late 2022 (gure8). Because prices for housing

services measure the rents paid by all tenants

(and the equivalent rent implicitly paid by all

homeowners)—including those whose leases

have not yet come up for renewal—they tend

to adjust slowly to changes in rental market

conditions. The softening in market rents

therefore points to a continued deceleration in

housing services prices over the year ahead.

Prices for nonhousing core services—a

broad group that includes services such as

travel and dining, nancial services, and car

repair—rose 3.5percent in the 12 months

ending in January, down from their recent

peak of 5.2percent (gure4, right panel).

As labor costs are a signicant input in these

service sectors, the ongoing softening of labor

demand and improvements in labor supply

should contribute to a further slowing in core

services price ination as labor cost growth

moderates.

Nonmanufacturing

45

50

55

60

65

70

75

80

Diusion index

20242023202220212020201920182017

6. Suppliers’ delivery times

Monthly

Manufacturing

NOTE: Values greater than 50 indicate that more respondents reported

longer delivery times relative to a month earlier than reported shorter

delivery times.

S

OURCE: Institute for Supply Management, Report on Business, via

Haver Analytics.

4

2

+

_

0

2

4

6

8

Percent change from year earlier

202420222020201820162014

7. Nonfuel import price index

Monthly

S

OURCE

: Bureau of Labor Statistics via Haver Analytics.

Zillow

RealPage

CoreLogic single-family detached

1.0

.5

+

_

0

.5

1.0

1.5

2.0

2.5

Percent change from month earlier

202420232022202120202019

8. Housing rents

Monthly

NOTE: CoreLogic data extend through December 2023. Zillow,

CoreLogic, and RealPage measure market-rate rents—that is, rents for a

new lease by a new tenant.

S

OURCE: Bureau of Economic Analysis, PCE, via Haver Analytics;

CoreLogic, Inc.; Zillow, Inc.; RealPage, Inc.; Federal Reserve Board sta

calculations.

PCE housing services

8 PART 1: RECENT ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL DEVELOPMENTS

Measures of longer-term ination

expectations have been stable, while

shorter-term expectations have

fallenback

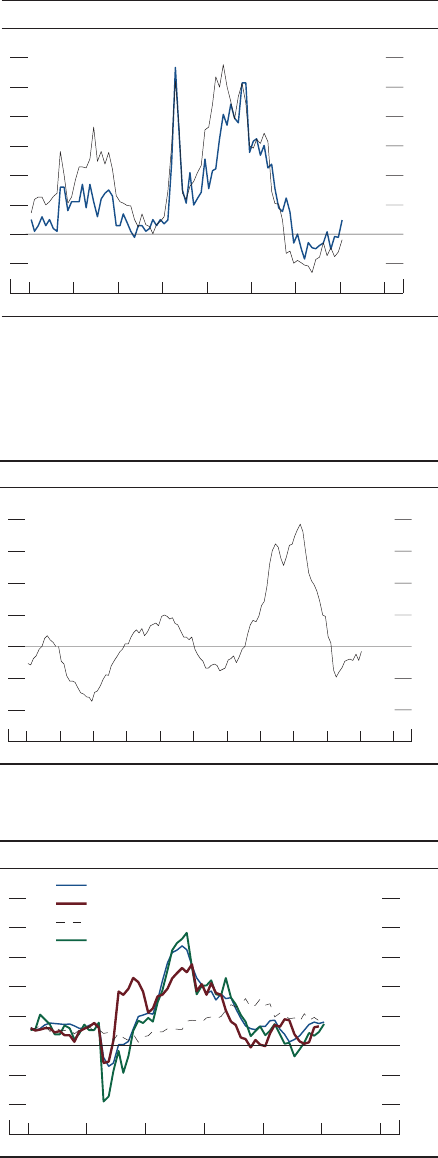

The generally held view among economists and

policy analysts is that ination expectations

inuence actual ination by aecting wage-

and price-setting decisions. Survey-based

measures of expected ination over a longer

horizon have generally been moving sideways

over the past year, within the range seen during

the decade before the pandemic, and they

appear broadly consistent with the FOMC’s

longer-run 2percent ination objective. This

development is seen for surveys of households,

such as the University of Michigan Surveys

of Consumers, and for surveys of professional

forecasters (gure9). For example, the median

forecaster in the Survey of Professional

Forecasters, conducted by the Federal Reserve

Bank of Philadelphia, continued to expect

PCE price ination to average 2percent over

the ve years beginning ve years fromnow.

Moreover, ination expectations over a shorter

horizon—which tend to follow observed

ination more closely—have been reversing

their earlier run-ups. In the Michigan survey,

the median value for ination expectations

over the next year was 3.0percent in February,

well below the peak rate of 5.4percent

observed in spring 2022. Expected ination

for the next year as measured in the Survey

of Consumer Expectations, conducted by

the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, has

also declined, on net, over this period and has

returned to the range of values seen before

thepandemic.

Market-based measures of longer-term

ination compensation, which are based on

nancial instruments linked to ination such

as Treasury Ination-Protected Securities,

are also broadly in line with readings seen in

the years before the pandemic and consistent

with ination returning to 2percent. These

measures have been little changed, on net,

since last summer (gure10).

SPF, next 10 years

Michigan survey, next 5 to 10 years

SPF, 6 to 10 years ahead

1.5

2.0

2.5

3.0

3.5

4.0

4.5

5.0

5.5

6.0

6.5

Percent

202420222020201820162014201220102008

9. Measures of ination expectations

NOTE: The Survey of Professional Forecasters (SPF) data are

quarterly and extend through 2024:Q1. The data for the Michigan surve

y

are monthly and extend through February 2024; the February data are

preliminary.

S

OURCE

: University of Michigan Surveys of Consumers; Federal

Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, SPF.

Michigan survey, next 12 months

5-year

0

.5

1.0

1.5

2.0

2.5

3.0

3.5

4.0

Percent

202420232022202120202019201820172016

10. Ination compensation implied by Treasury

Ination-Protected Securities

Daily

5-to-10-year

N

OTE:The data are at a business-day frequency and are estimated

from smoothed nominal and ination-indexed Treasury yield curves.

S

OURCE: Federal Reserve Bank of New York; Federal Reserve Board

sta calculations.

MONETARY POLICY REPORT: MARCH 2024 9

Black or African American

Asian

Hispanic or Latino

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

16

18

20

Percent

2024202220202018201620142012201020082006

13. Unemployment rate, by race and ethnicity

Monthly

White

N

OTE

: Unemployment rate measures total unemployed as a percentage of the labor force. Persons whose ethnicity is identied as Hispanic or Latino

may

be of any race. Small sample sizes preclude reliable estimates for Native Americans and other groups for which monthly data are not reported b

y

the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

S

OURCE

: Bureau of Labor Statistics via Haver Analytics.

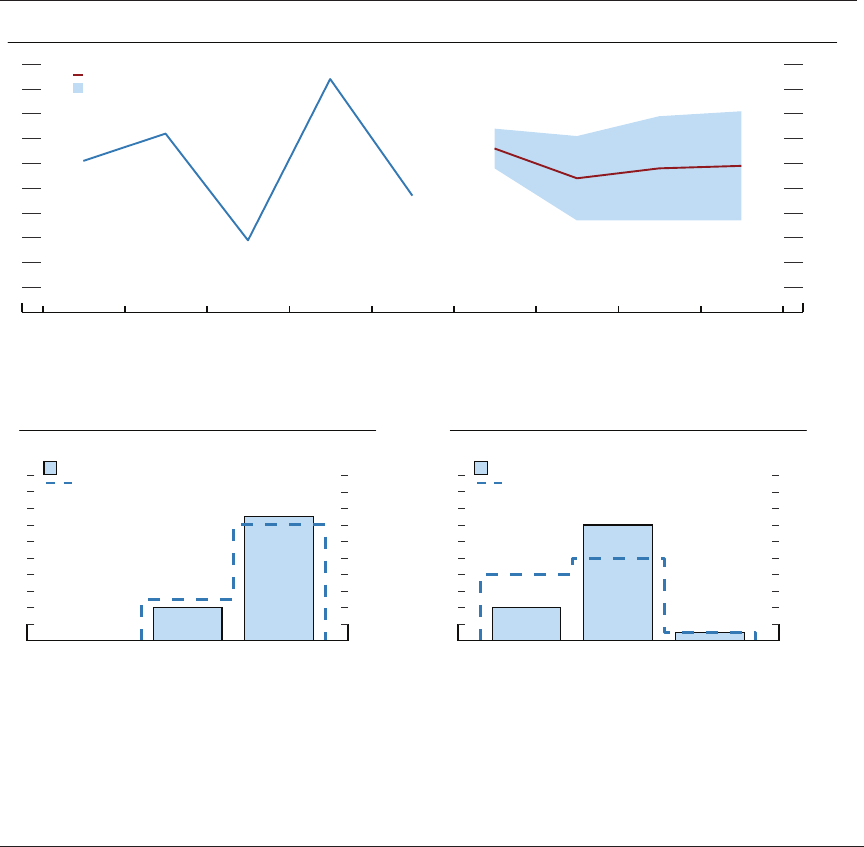

The labor market remains strong

Payroll employment gains have been robust,

averaging 239,000 since June of last year.

The pace of job gains has nevertheless been

softening, having averaged more than 375,000

per month in 2022 and about 290,000 in the

rst half of 2023 (gure11). This slowing

has come primarily from the professional and

business services, manufacturing, and leisure

and hospitality sectors, which tend to be

cyclically sensitive. In contrast, employment

growth has remained strong in the health-

care and social assistance sector and at state

and local governments, which tend to be less

cyclically sensitive and are still recovering from

pandemic-era stang shortages.

The unemployment rate edged up, on net,

since the middle of last year, but at 3.7percent

in January, it is only slightly above its pre-

pandemic level and remains very low by

historical standards (gure12). Indeed,

unemployment rates among most age,

educational attainment, sex, and ethnic and

racial groups are near their respective historical

lows (gure13). (The box “Employment

and Earnings across Demographic Groups”

provides further details.)

100

200

300

400

500

600

700

800

Thousands of jobs

2024202320222021

11. Nonfarm payroll employment

Monthly

N

OTE

: The data shown are a 3-month moving average of the change in

nonfarm payroll employment.

S

OURCE

: Bureau of Labor Statistics via Haver Analytics.

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

Percent

2024202220202018201620142012201020082006

12. Civilian unemployment rate

Monthly

S

OURCE

: Bureau of Labor Statistics via Haver Analytics.

10 PART 1: RECENT ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL DEVELOPMENTS

workers was also historically high in early 2023,

although it has since moved down closer to its

2019level.

3

Similarly, the EPOP ratio for prime-age women

increased steadily over the past two years and reached

a record high in 2023 ( gureA, right panel). As a

result, the EPOP ratio gap between prime-age men

and women fell to a record low. The recent increase in

female employment is mostly attributable to rising labor

force participation, which had also been increasing

briskly before the pandemic, bolstered by a growing

share of women with a college degree.

4

Other factors,

including tight labor market conditions and greater

availability of remote-work options, may have also

contributed to rising prime-age female labor force

participation.

5

3. As monthly series have greater sampling variability

for smaller groups, we do not plot EPOP ratio estimates for

American Indians or Alaska Natives.

4. For a discussion of the contribution of educational

attainment to prime-age female labor force participation

before the pandemic, see Didem Tüzemen and Thao Tran

(2019), “The Uneven Recovery in Prime-Age Labor Force

Participation,” Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City,Economic

Review, vol. 104 (Third Quarter), pp. 21–41, https://www.

kansascityfed.org/Economic%20Review/documents/652/2019-

The%20Uneven%20Recovery%20in%20Prime-Age%20

Labor%20Force%20Participation.pdf.

5. For a discussion on access to remote work and

participation rates, see Maria D. Tito (2024), “Does the

Ability to Work Remotely Alter Labor Force Attachment?

An Analysis of Female Labor Force Participation,” FEDS

Notes (Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal

Reserve System, January19), https://doi.org/10.17016/2380-

7172.3433.

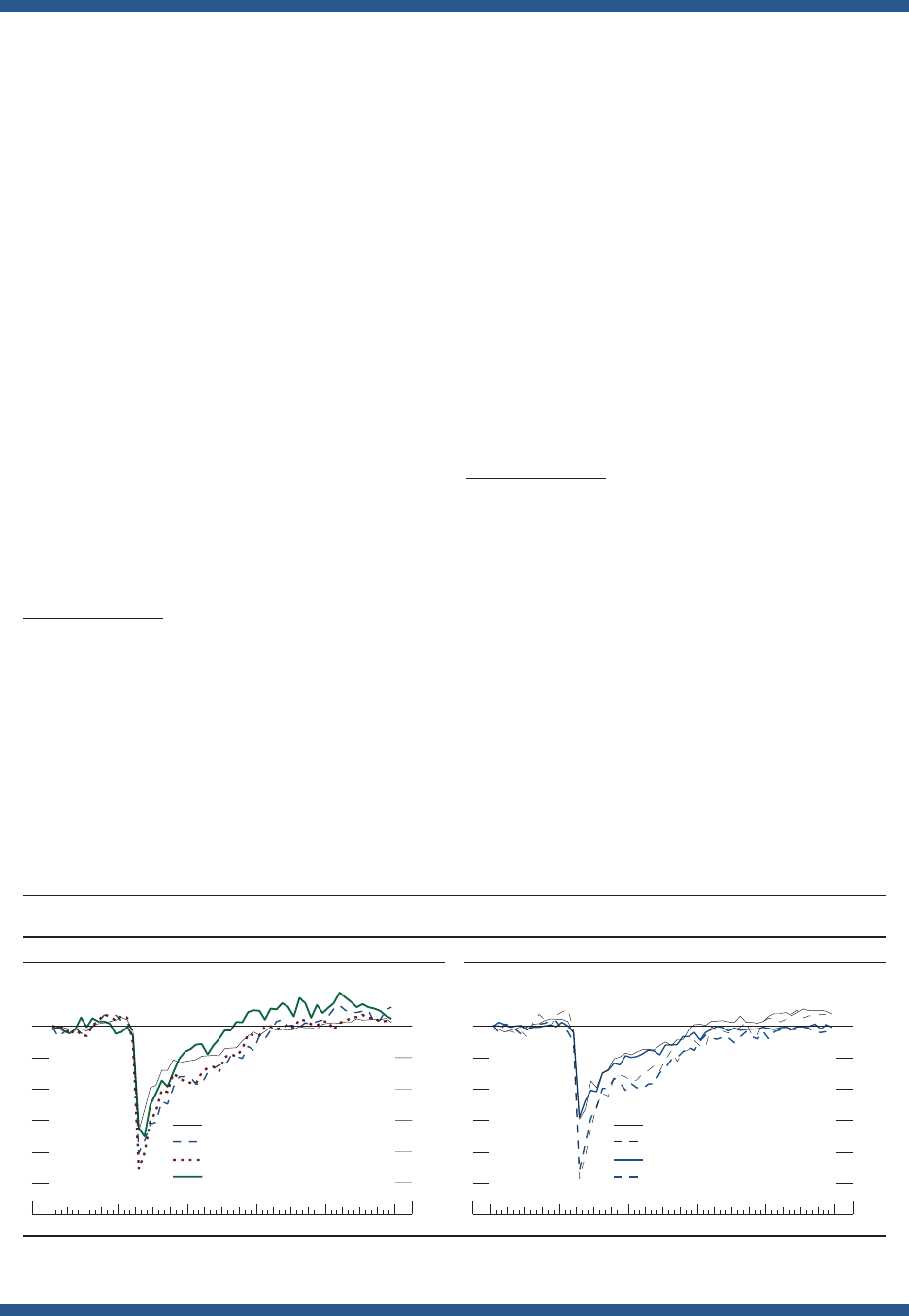

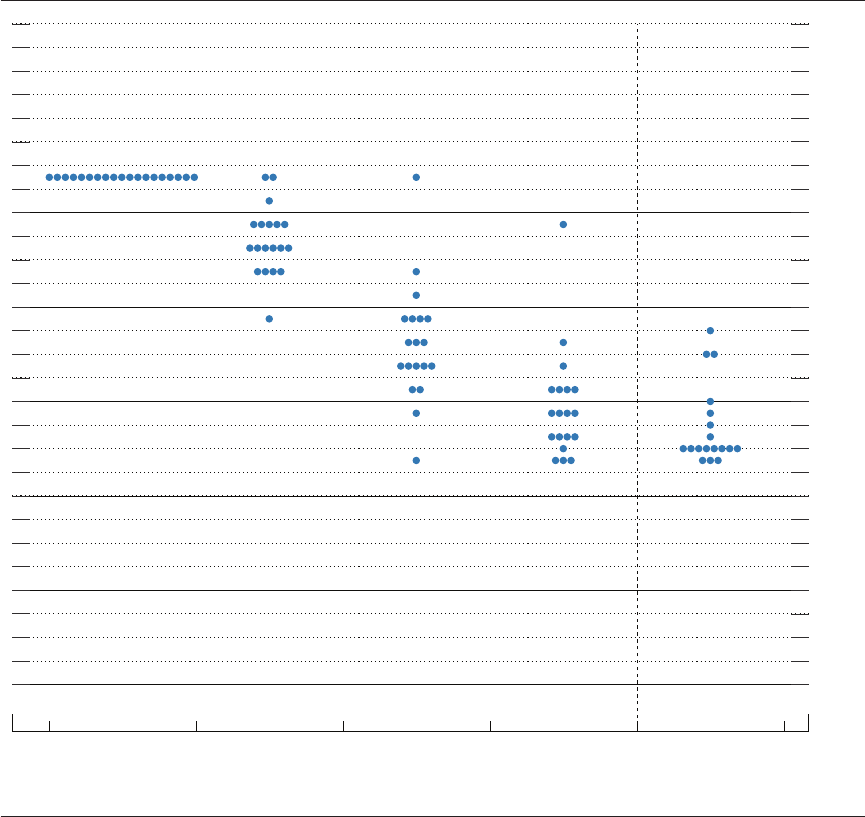

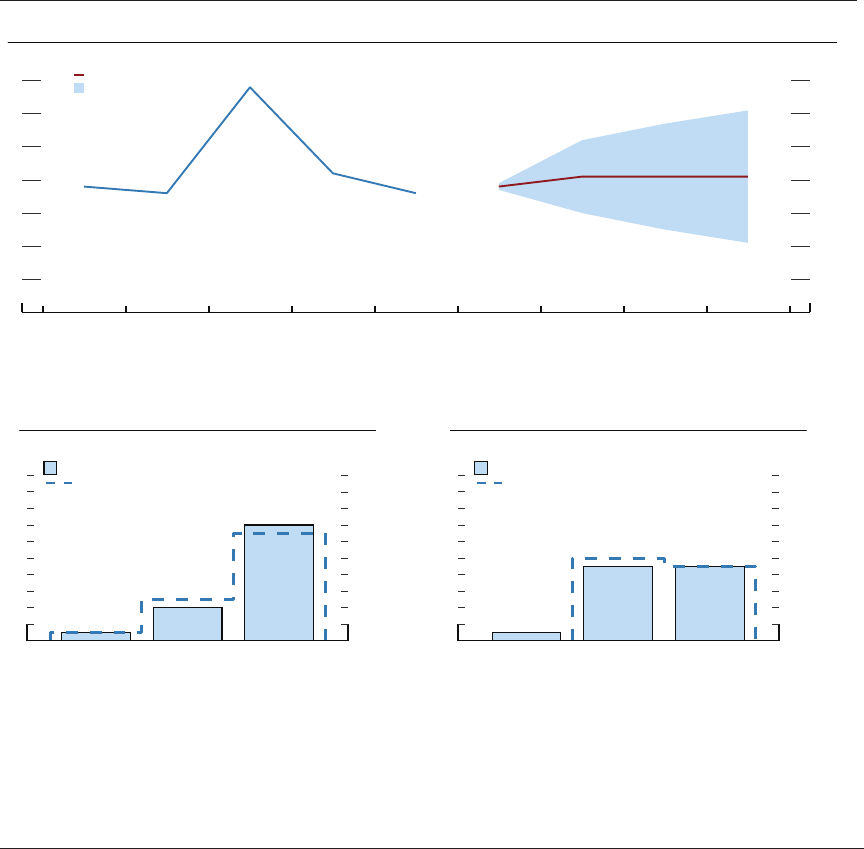

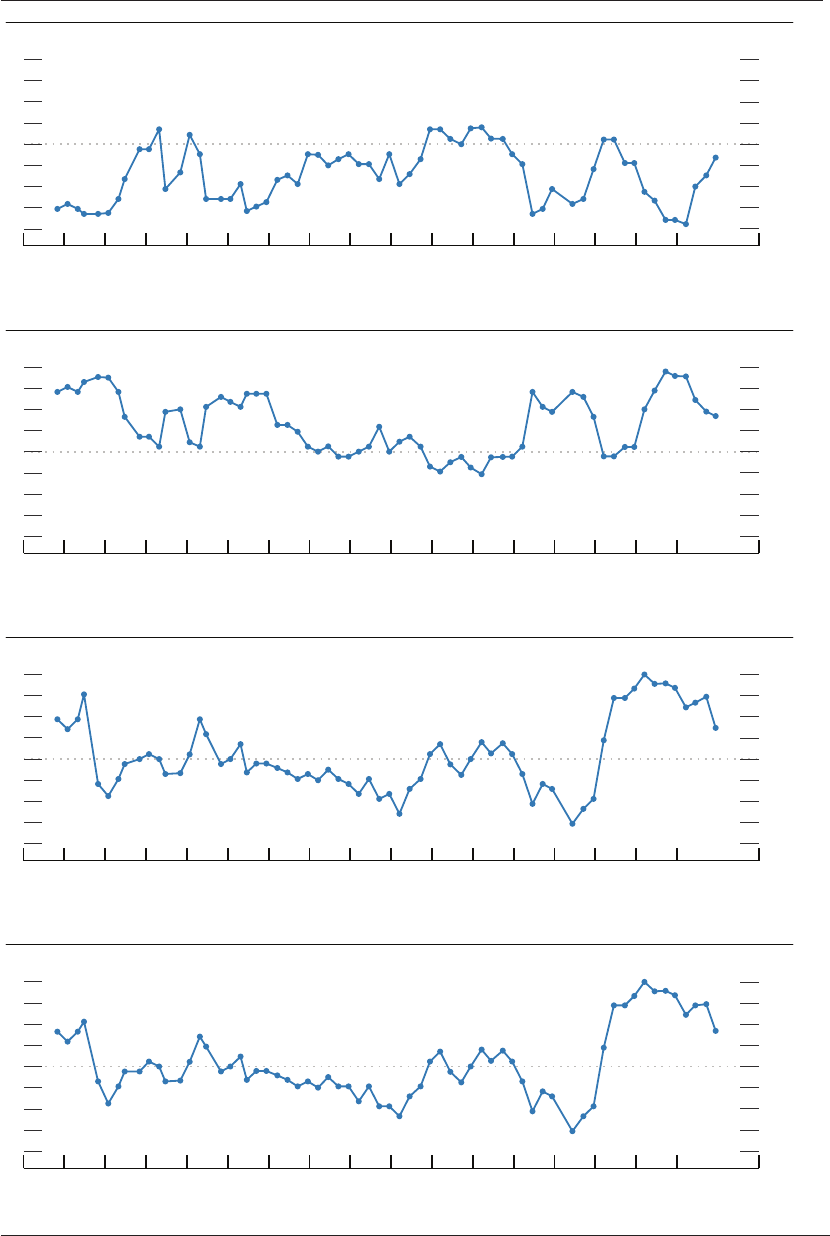

Economic expansions have tended to narrow long-

standing disparities in employment and earnings across

demographic groups, which can help make up for

disproportionate losses experienced during downturns.

These bene ts have been especially pronounced during

the current expansion, which has been characterized

by an exceptionally tight labor market and robust

demand for workers over the past two years.

Among prime-age individuals (ages 25 to 54),

employment for Black or African American workers,

which declined more relative to white and Asian

workers in early 2020, reached a historical peak in

2023 ( gureA, left panel). As a result, the gap in the

employment-to-population (EPOP) ratio between

prime-age Black and white workers fell to its lowest

point in almost 50years.

1

Hispanic or Latino workers

experienced especially large employment losses in

2020, due in part to greater exposure to the industries

most affected by the pandemic.

2

By early 2022,

however, this group’s EPOP ratio gap relative to prime-

age white workers had recovered to its 2019 average

and has remained near this historically low level for the

past two years. The EPOP ratio for prime-age Asian

1. In fact, for the population aged 16 or older, the

EPOP ratio was the same for Black and white individuals

in January2024 (not shown). This equivalence, however,

partly re ects the fact that these groups have different age

distributions, with whites older, on average, and thus more

likely to be retired.

2. On the relationship between occupation, industry, and

the differential effect of the COVID-19 pandemic across

demographic groups, see Guido Matias Cortes and Eliza

Forsythe (2023), “Heterogeneous Labor Market Impacts of the

COVID-19 Pandemic,” ILR Review, vol. 76 (January), pp.30–55.

(continued)

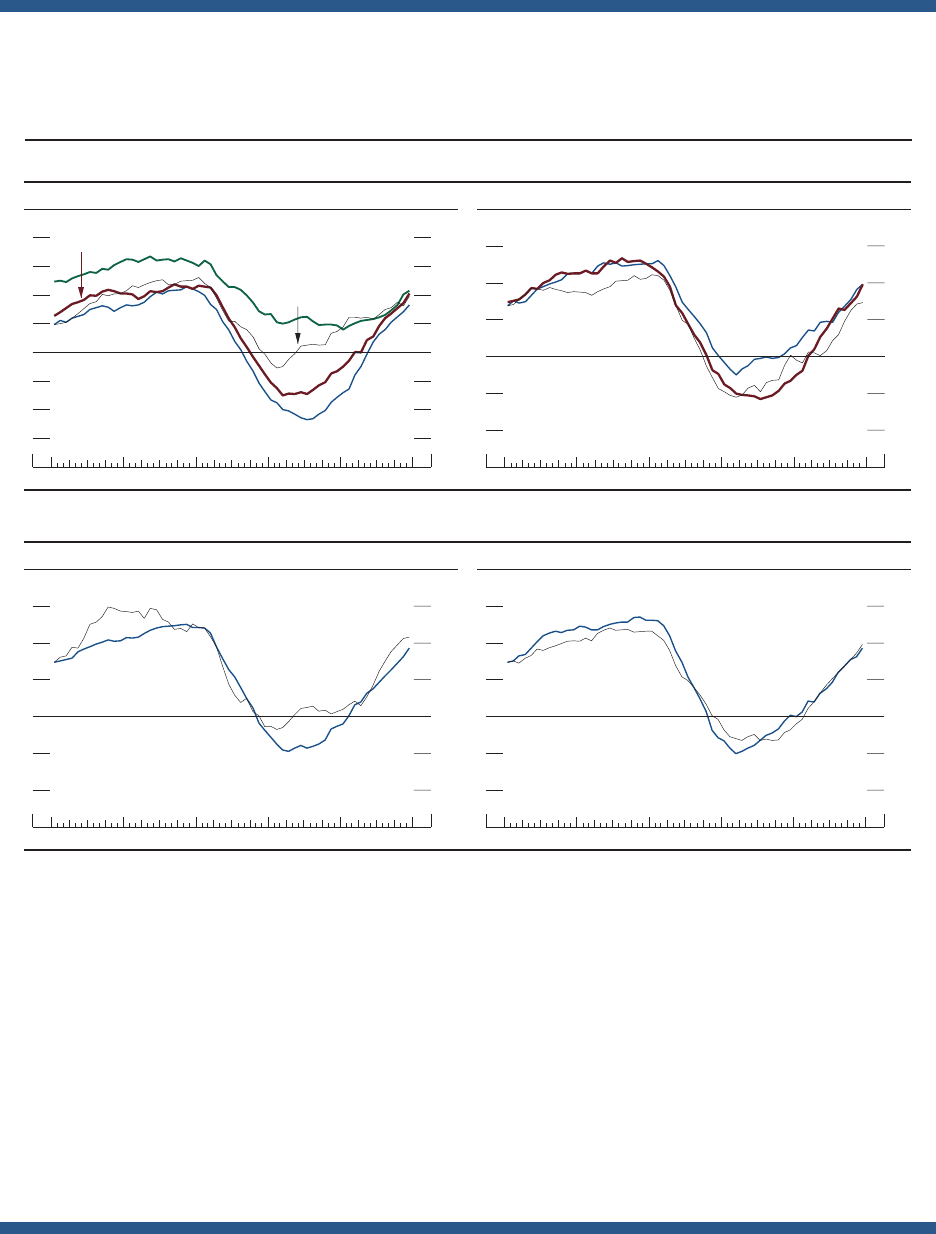

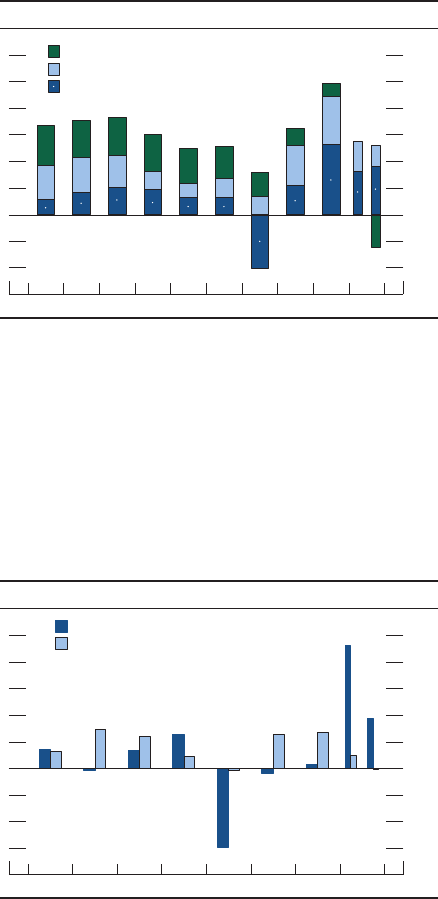

Employment and Earnings across Demographic Groups

Black or African American

Men, some college or more

Men, high school or lessAsian

Hispanic or Latino

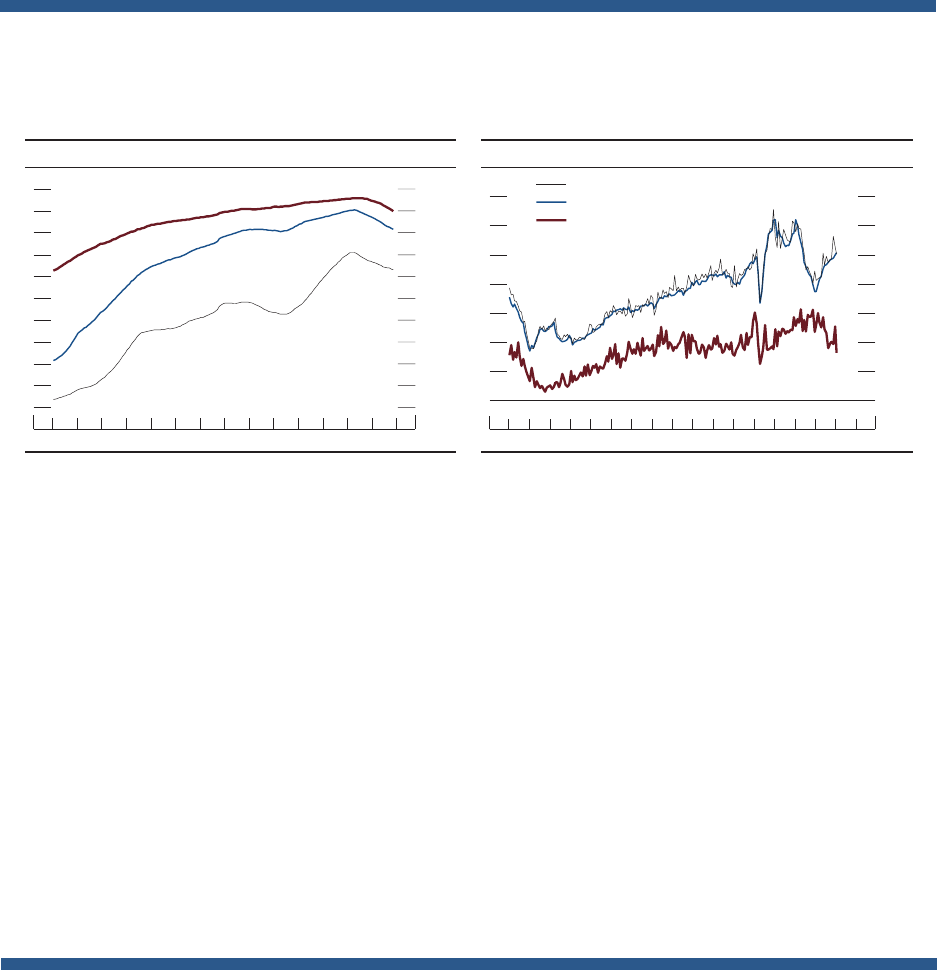

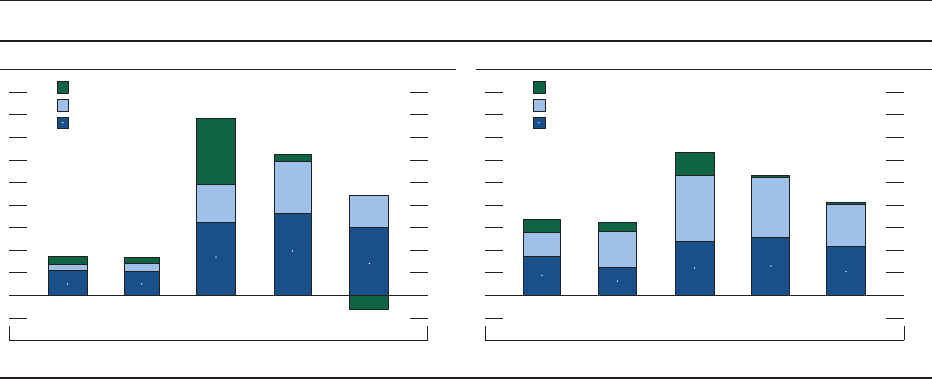

15

12

9

6

3

+

_

0

3

Percentage points

20232022202120202019

Race and ethnicity

Monthly

NOTE: The data extend through December 2023. Prime age is 25 to 54. All series are seasonally adjusted by the Federal Reserve Board sta.

SOURCE: Bureau of Labor Statistics; U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Survey; Federal Reserve Board sta calculations.

White

15

12

9

6

3

+

_

0

3

Percentage points

20232022202120202019

Sex and educational attainment

Monthly

Women, some college or more

Women, high school or less

A. Prime-age employment-to-population ratios compared with the 2019 average ratio, by group

MONETARY POLICY REPORT: MARCH 2024 11

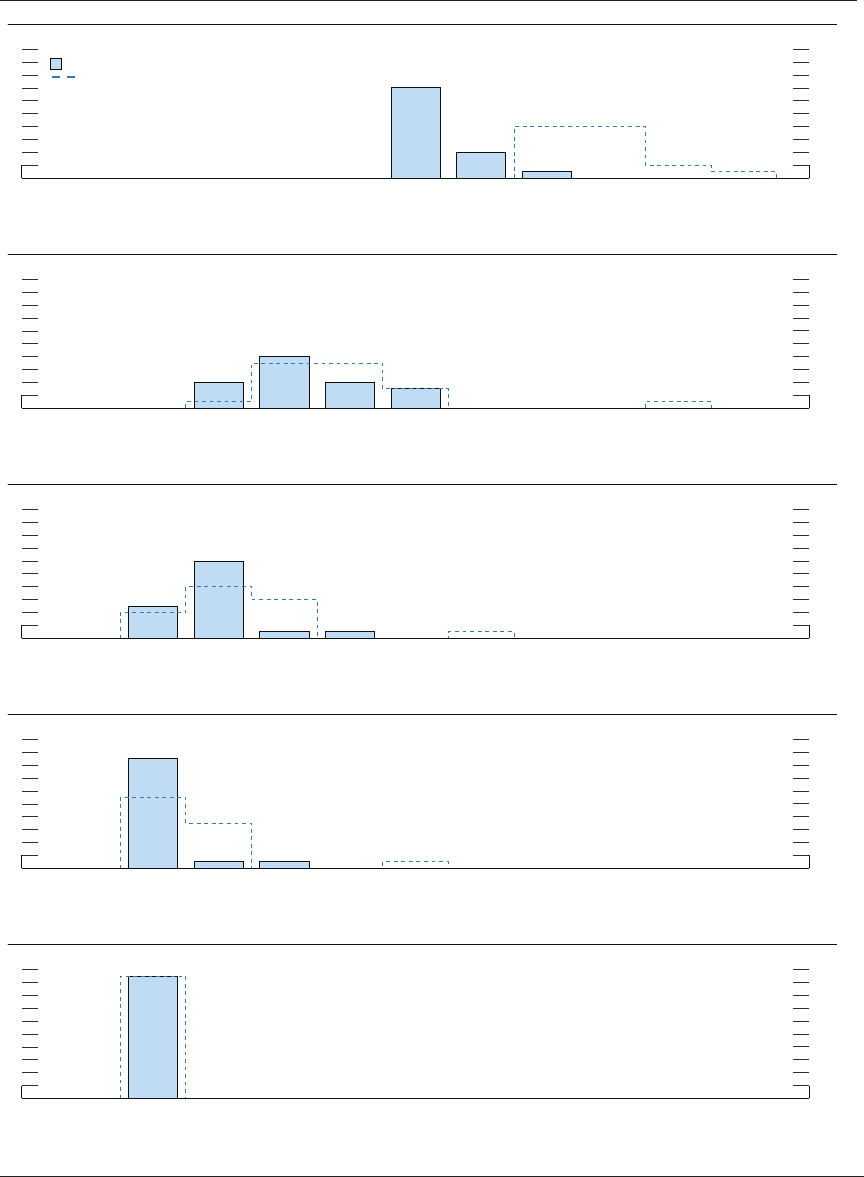

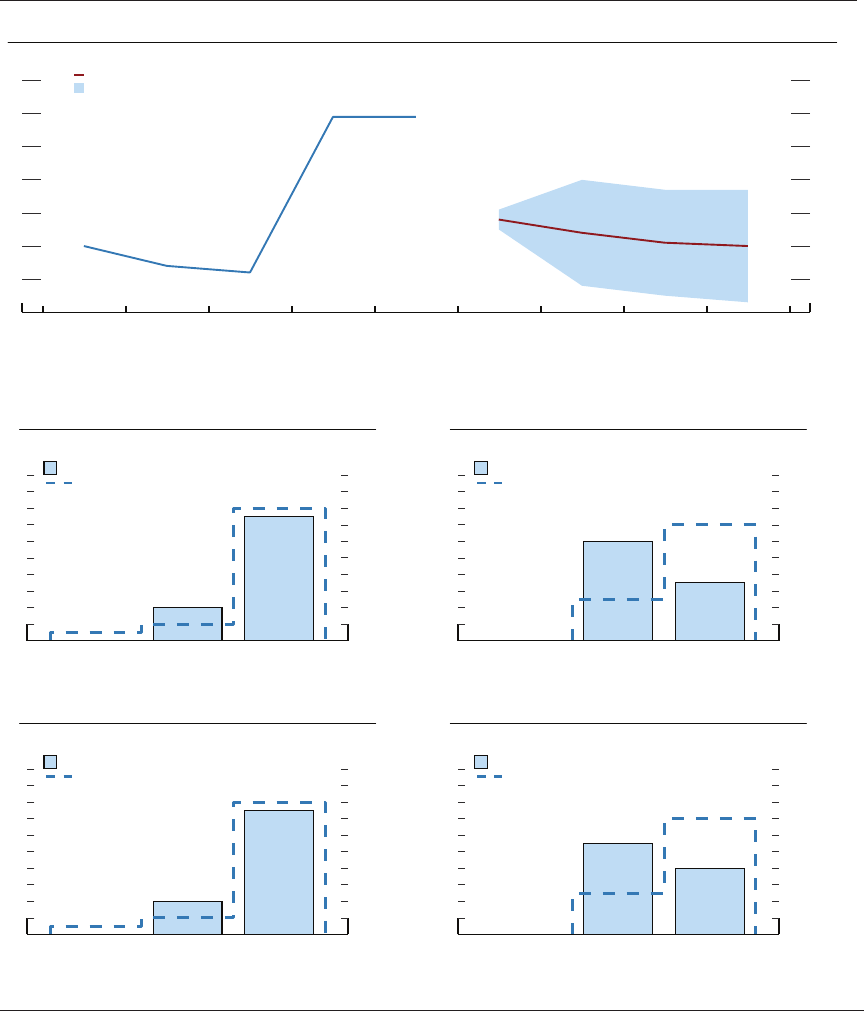

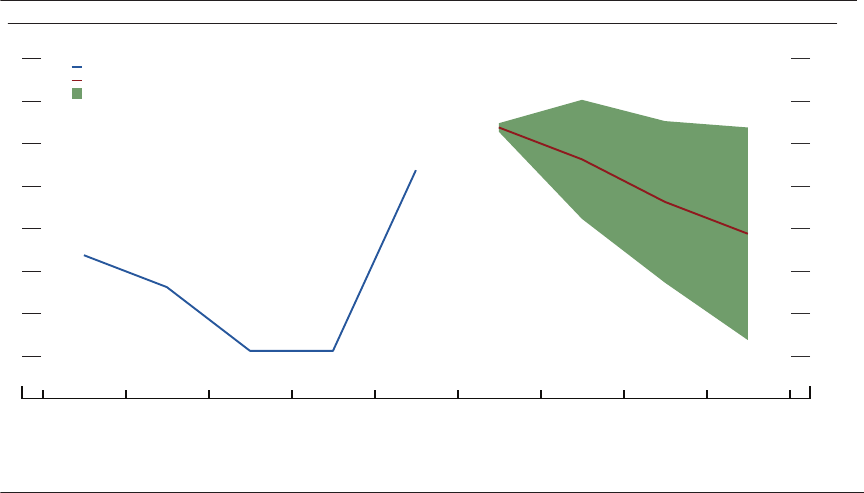

two years have also led to strong nominal wage growth,

especially for groups at the lower end of the earnings

distribution. As shown in the top-left panel of gureC,

real wage growth—as measured by the Federal Reserve

Bank of Atlanta’s Wage Growth Tracker and de ated by

the personal consumption expenditures price index—

has been consistently stronger for workers in lower

wage quartiles.

9

Stronger wage growth at the bottom of the income

distribution is re ected in the experiences of different

education and demographic groups. In the rst two

years of the recovery, real wage growth was stronger

for workers with a high school diploma or less relative

to workers with a bachelor’s degree or more ( gureC,

top-right panel) and, in the past two years, has also

been stronger for nonwhite workers relative to white

workers ( gureC, bottom-left panel). Wages for men

and women, by contrast, have largely grown in tandem

( gureC, bottom-right panel).

10

In addition to the

in uence of a tight labor market, differences in wage

9. To reduce noise due to sampling variation, which can

be pronounced when considering disaggregated groups’

wage changes, the series shown in gure C are the 12-month

moving averages of the groups’ median 12-month real wage

changes. Thus, by construction, these series lag the actual real

wage changes.

10. The measure of real earnings growth shown in the

gure uses the same price index for all groups, but in ation

experiences can differ across demographic groups because

of differences in what they purchase or where they shop.

See Jacob Orchard (2021), “Cyclical Demand Shifts and

Cost of Living Inequality,” working paper, February (revised

September2022).

Robust labor demand over the past two years has

also reversed pandemic-induced employment losses

across education groups. For both prime-age men

and women, the EPOP ratio fell signi cantly more for

workers with a high school diploma or less compared

with those with at least some college education, largely

re ecting industry exposure to pandemic-related

closures or some differences in the ability to work

remotely across jobs. Notably, the EPOP ratio declined

similarly for men and women with the same education

level, a result that contrasts with those in previous

recessions, in which male EPOP losses have historically

outpaced female losses.

6

The unusually large effect on

women during the pandemic also re ects the industry

composition of job losses, as well as caregiving needs.

7

While employment disparities across many

demographic groups are now within historically narrow

ranges, substantial gender, racial, and ethnic gaps

remain, underscoring long-standing structural factors.

Currently, prime-age women are employed at a rate

11percentage points less than men, while prime-age

Black and Hispanic workers are employed at a rate

3 to 4percentage points less than white workers.

Further, the differential effect of the pandemic on

the employment of older workers has proven highly

persistent. The EPOP ratio for workers aged 55 or older

remains approximately 2percentage points below its

pre-pandemic level and has changed little since late

2021 ( gureB). This shortfall is wholly attributable to

decreases in labor force participation stemming from

increased retirements concentrated among workers

aged 60 or older.

8

In addition to narrowing many employment gaps,

historically tight labor market conditions over the past

6. See Claudia Goldin (2022), “Understanding the

Economic Impact of COVID-19 on Women,” Brookings Papers

on Economic Activity, Spring, pp. 65–110, https://www.

brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/16265-BPEA-

Sp22_Goldin_WEB-Appendix.pdf; and Stefania Albanesi and

Jiyeon Kim (2021), “Effects of the COVID-19 Recession on the

US Labor Market: Occupation, Family, and Gender,” Journal of

Economic Perspectives, vol. 35 (Summer), pp. 3–24.

7. On the role of caregiving, see Joshua Montes,

Christopher Smith, and Isabel Leigh (2021), “Caregiving for

Children and Parental Labor Force Participation during the

Pandemic,” FEDS Notes (Washington: Board of Governors

of the Federal Reserve System, November5), https://www.

federalreserve.gov/econres/notes/feds-notes/caregiving-for-

children-and-parental-labor-force-participation-during-the-

pandemic-20211105.html.

8. For an analysis on the increase in retirements following

the pandemic, see Joshua Montes, Christopher Smith, and

Juliana Dajon (2022), “ ‘The Great Retirement Boom’: The

Pandemic-Era Surge in Retirements and Implications for Future

Labor Force Participation,” Finance and Economics Discussion

Series 2022-081 (Washington: Board of Governors of the

Federal Reserve System, November), https://doi.org/10.17016/

FEDS.2022.081.

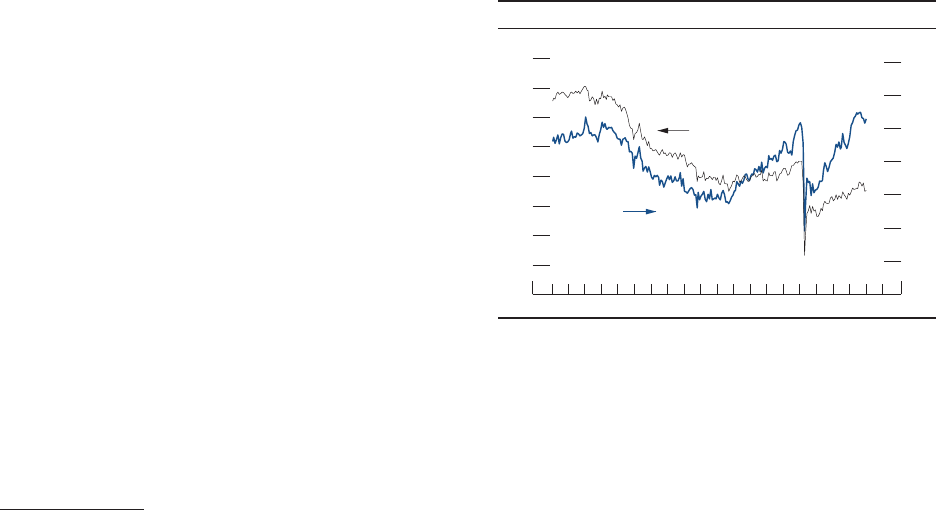

Ages 16 to 24

Ages 55+

15

12

9

6

3

+

_

0

3

Percentage points

20232022202120202019

B. Employment-to-population ratios relative to 2019

average, by age

Monthly

Ages 25 to 54

N

OTE

: The data extend through December 2023. Data before Januar

y

2023

are estimated by Federal Reserve Board sta in order to eliminat

e

discontinuities in the published history.

S

OURCE

:Bureau of Labor Statistics; U.S. Census Bureau, Curren

t

Population Survey; Federal Reserve Board sta calculations.

(continued on next page)

12 PART 1: RECENT ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL DEVELOPMENTS

growth across groups have narrowed considerably.

While the labor market is still tight by historical

standards, factors disproportionately boosting wage

growth for the lowest earners have largely faded. In

2023, nominal wage growth slowed for workers with

below-median earnings but stepped up for workers

above the median. Even so, the gaps in relative wages

between workers in the rst three quartiles and those

in the highest quartile continue to close, albeit at a

slowerpace.

growth across groups partially re ect factors speci c

to the post-pandemic recovery, such as the sectoral

composition of labor demand and supply. Wages, for

instance, grew faster than average in the leisure and

hospitality industry, a relatively low-wage sector that

suffered disproportionate employment losses during

the pandemic, followed by a surge in vacancies that

employers struggled to ll as the economy reopened.

Over the past year, real wages have been rising for

all groups shown here, and differences in real wage

Employment and Earnings (continued)

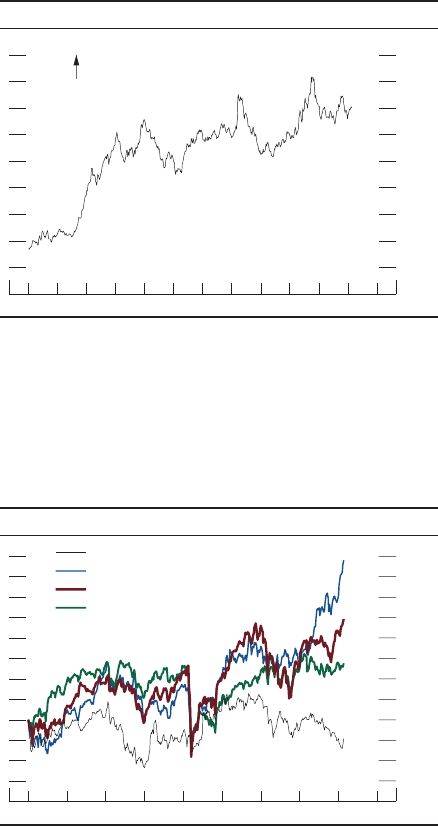

4th quartile

High school or less

1st quartile3rd quartile

Bachelor’s degree or more

3

2

1

+

_

0

1

2

3

4

Percent

20232022202120202019

Wage quartiles

Monthly

2nd quartile

2

1

+

_

0

1

2

3

Percent

20232022202120202019

Educational attainment

Monthly

Associate’s degree

C. Median real wage growth, by group

White

Men

2

1

+

_

0

1

2

3

Percent

20232022202120202019

Race

Monthly

Nonwhite

2

1

+

_

0

1

2

3

Percent

20232022202120202019

Sex

Monthly

N

OTE

: The data extend through December 2023. Series show 12-month moving averages of the median percent change in the hourly wage o

f

individuals

observed 12 months apart, deated by the 12-month moving average of the 12-month percent change in the personal con

sumption

expenditures

price index. In the top-left panel, workers are assigned to wage quartiles based on the average of their wage reports in both

Current

Population Survey outgoing rotation group interviews; workers in the lowest 25 percent of the average wage distribution are ass

igned to the 1st quartile,

and those in the top 25 percent are assigned to the 4th quartile.

S

OURCE

: Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, Wage Growth Tracker; Bureau of Labor Statistics; U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Survey.

Women

MONETARY POLICY REPORT: MARCH 2024 13

Labor demand has been gradually

cooling. . .

Demand for labor continued to cool last year

but remains robust. The Job Openings and

Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS) indicated

that there were nearly 9million job openings

at the end of 2023—down about 3million

from the all-time high recorded in March2022

but still around 2million above pre-pandemic

levels. An alternative measure of job vacancies

constructed by the Federal Reserve Board

sta using job postings data from the large

online job board Indeed also shows that

vacancies continued to move gradually

lower through mid-February but remained

above pre-pandemic levels. In addition,

measures of layos, such as initial claims

for unemployment insurance and the rate of

layos and discharges in the JOLTS, have

remained very low by historical standards.

. . . and labor supply has increased

further . . .

Meanwhile, the supply of labor has

continued to increase on net. The labor force

participation rate, which measures the share of

people either working or actively seeking work,

continued to trend higher for most of last year

but has softened in recent months (gure14).

Importantly, labor force participation for

prime-age workers increased notably through

last September and, although it has edged

down more recently, remains above its pre-

pandemic level.

Labor supply was also boosted last year by

relatively strong population growth. The

Census Bureau estimates that the resident

population increased 1.7million (0.5percent)

in 2023, with almost 70percent of that

increase coming from immigration.

2

Last

2. A recent report from the Congressional Budget

Oce estimates that immigration has been considerably

higher than in the Census Bureau’s estimates in recent

years; see Congressional Budget Oce (2024), The

Demographic Outlook: 2024 to 2054 (Washington: CBO,

January), https://www.cbo.gov/publication/59697. The

labor force estimates published by the Bureau of Labor

Statistics are based on the civilian noninstitutionalized

population aged 16 or older, which constitutes about

80percent of the resident population.

Ages 25 to 54

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

Percent

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

2024202220202018201620142012201020082006

14. Labor force participation rate, by age

Percent

Ages 16+

N

OTE: The labor force participation rate is a percentage of the relevant

population. Data are monthly, and values before January 2023 are

estimated by Federal Reserve Board sta in order to eliminate

discontinuities in the published history.

S

OURCE: Bureau of Labor Statistics via Haver Analytics; U.S. Census

Bureau; Federal Reserve Board sta calculations.

14 PART 1: RECENT ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL DEVELOPMENTS

year’s rate of population growth was slightly

faster than in 2022 and about twice as fast as

in 2020 and 2021, when growth was held down

by COVID-19-related increases in mortality

and restrictions on immigration. Although

population growth has largely returned to its

pace from the years preceding the pandemic,

it remains well below its average from

1990 to2015.

. . . but the labor market remains

relatively tight

Even with easing labor demand and rising

labor supply, the labor market remains

relatively tight. Some indicators suggest that

the labor market remains tighter than before

the pandemic, while others have returned

to their 2019 ranges, when the labor market

was also relatively tight. The number of total

available jobs (measured by employed workers

plus job openings) still exceeds the number

of available workers (measured by the labor

force). This jobs–workers gap was around

2.8million in December, down markedly from

its peak of 6.0million recorded in March2022

but still above its 2019 average of 1.1million

(gure15).

3

In contrast, the percentage of

workers quitting their jobs each month, an

indicator of the availability of attractive job

prospects, was 2.2percent in December, close

to its 2019 average. Surveys indicate that

households’ and small businesses’ perceptions

of labor market tightness have also come down

from their recent peaks. In addition, business

contacts in nearly all Federal Reserve Districts

cited signs of a cooling labor market, such

as larger applicant pools and lower turnover

rates; however, some employers continued to

report diculty nding workers, particularly

employers seeking specialized skills.

4

3. The ratio of job openings to unemployment shows

that there were 1.4job openings per unemployed person

in December2023. For comparison, this ratio averaged

1.2 in 2019 and 0.6 over the 10-year period from 2010

to2019.

4. See the January2024 Beige Book, available on

the Board’s website at https://www.federalreserve.gov/

monetarypolicy/publications/beige-book-default.htm.

Available workers

135

140

145

150

155

160

165

170

175

Millions

2023202120192017201520132011200920072005

15. Available jobs versus available workers

Monthly

N

OTE

: The data extend through December 2023. Available jobs are

employment plus job openings as of the end of the previous month.

Available workers are the labor force. Data for employment and labor

force before January 2023 are estimated by Federal Reserve Board sta

in order to eliminate discontinuities in the published history.

S

OURCE

: Bureau of Labor Statistics via Haver Analytics; U.S. Census

Bureau; Federal Reserve Board sta calculations.

Available jobs

MONETARY POLICY REPORT: MARCH 2024 15

Wage growth has slowed but

remainselevated

Consistent with the easing in labor market

tightness, nominal wage growth slowed in 2023

but remains elevated (gure16). Total hourly

compensation as measured by the employment

cost index increased 4.2percent over the

12months ending in December, a noticeable

slowing from the 5.1percent increase in 2022.

Other aggregate measures, such as average

hourly earnings (a less comprehensive measure

of compensation) and the Federal Reserve

Bank of Atlanta’s Wage Growth Tracker,

which reports the median 12-month wage

growth of individuals responding to the

Current Population Survey, have slowed as

well. With PCE prices having risen 2.6percent

in 2023, these measures suggest that most

workers saw increases in the purchasing power

of their wages over the pastyear.

Labor productivity strengthened last year

The extent to which nominal wage gains raise

rms’ costs and act as a source of ination

pressure depends importantly on the pace of

productivity growth. Labor productivity in the

business sector has been extremely variable

since the pandemic began, increasing sharply

in 2020 and then declining, on average, over

2021 and 2022 (gure17). Productivity is

reported to have risen a robust 2.7percent

last year. When averaged over the pandemic

period, output per hour rose at a moderate

average annual rate of 1½percent, in line with

the average rate of growth observed during the

business cycle from the fourth quarter of 2007

to the fourth quarter of 2019.

As always, the pace of future productivity

growth remains highly uncertain. It is possible

that productivity growth could remain at

around this same moderate pace. However,

it is also possible that the rapid adoption of

new technologies like articial intelligence

and robotics—as well as the high rate of new

business formation that the pandemic brought

about—could boost productivity growth above

that pace in coming years.

Average hourly earnings, private sector

Employment cost index, private sector

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

Percent change from year earlier

20242023202220212020201920182017

16. Measures of change in hourly compensation

Atlanta Fed’s Wage Growth Tracker

NOTE: For the private-sector employment cost index, change is over

the

12 months ending in the last month of each quarter; for

private-sector

average hourly earnings, the data are 12-month percent changes; for

the

Atlanta Fed’s Wage Growth Tracker, the data are shown as a

3-month

moving average of the 12-month percent change.

SOURCE

: Bureau of Labor Statistics; Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta,

Wage Growth Tracker; all via Haver Analytics.

94

96

98

100

102

104

106

108

110

112

2017 average = 100

202320212019201720152013

17. U.S. labor productivity

Quarterly

NOTE: The data are output per hour in the business sector.

SOURCE: Bureau of Labor Statistics via Haver Analytics.

16 PART 1: RECENT ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL DEVELOPMENTS

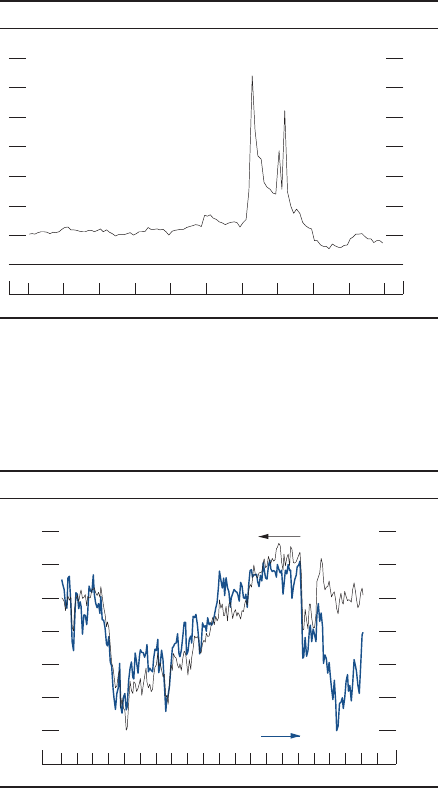

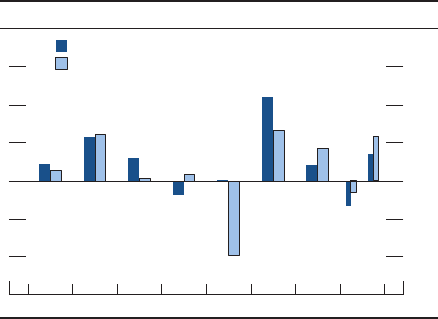

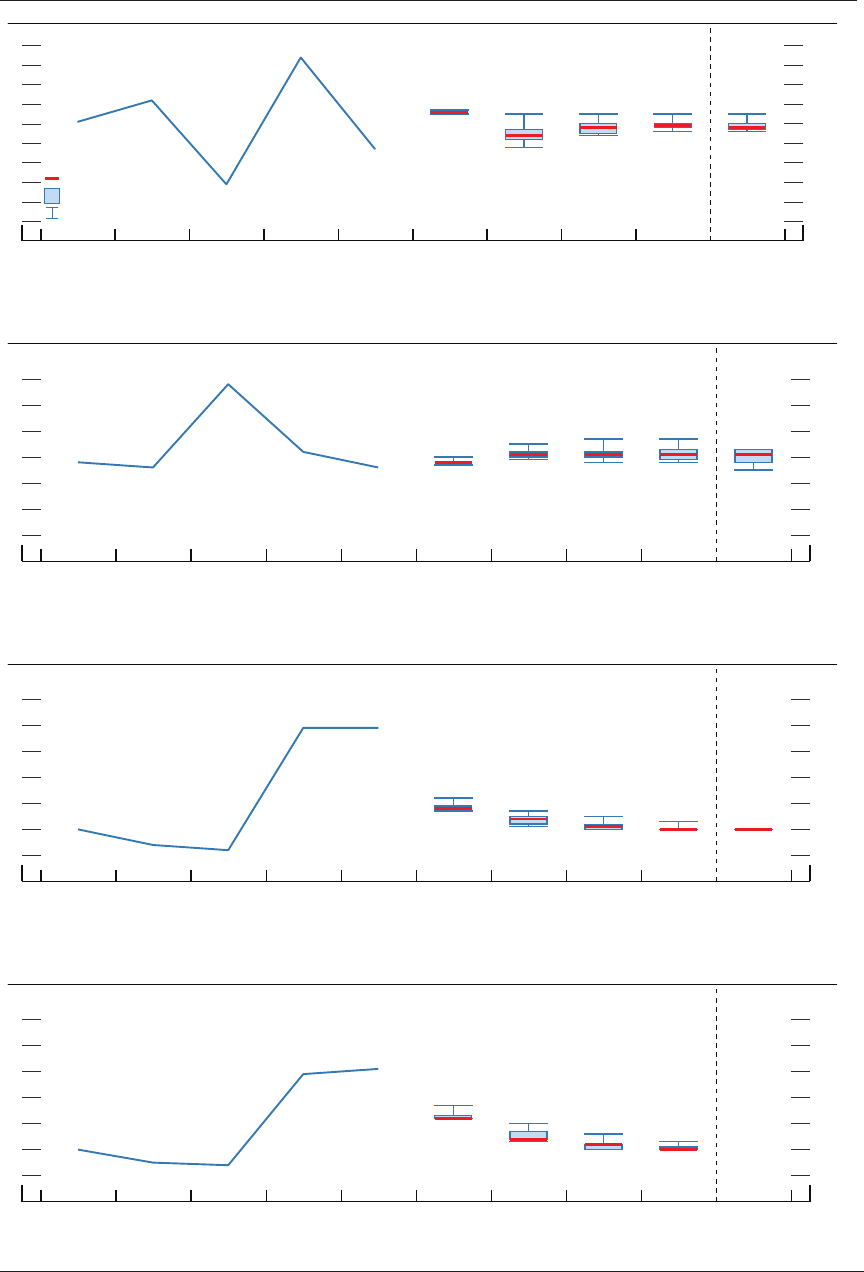

Gross domestic product rose at a solid

pace last year

Real gross domestic product (GDP) is

reported to have increased at an annual rate

of 4.0percent in the second half of 2023,

up from 2.2percent in the rst half. For

2023 as a whole, GDP increased 3.1percent,

notably faster than in 2022 despite restrictive

nancial conditions, including elevated longer-

term interest rates (gure18).

5

Among the

components of GDP, consumer spending rose

solidly in the second half of last year, and

residential investment started to turn back up

following its earlier sharp declines, but growth

of business investment slowed.

In contrast to GDP, manufacturing output

was little changed, on net, last year, a

downshift following two years of robust post-

pandemic gains. Motor vehicle production

continued to rebound from supply chain

disruptions in 2021 and 2022, although last

year’s production was held down by strikes at

several major automakers. Outside of motor

vehicles, industrial production generally

moved sideways last year, but it was down

from its post-pandemic peak in early 2022,

as inventories normalized and new orders

fellback.

Consumer spending growth was resilient

even as household nances deteriorated

Consumer spending adjusted for ination grew

at a solid rate of 3.0percent in the second half

of 2023 and 2.7percent for last year as a whole

(gure19). Consumers’ resilience in the face

5. Real gross domestic income (GDI) has been

notably weaker than GDP in recent quarters; both series

measure the same economic concept, and any dierence

between the two gures reects measurement error. GDI

reportedly increased at a 0.8percent pace in the rst three

quarters of last year after having been unchanged over

the four quarters of 2022—well below the corresponding

gures for GDP. As a result, productivity calculated from

the income side of the national accounts would also be

considerably weaker than the published gures over the

past couple of years.

1

+

_

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

Percent, annual rate

20232022202120202019201820172016

18. Change in real gross domestic product and gross

domestic income

H1

H2

H1

H2

N

OTE

: The data for gross domestic income extend through 2023:H1.

The key identies bars in order from left to right.

S

OURCE

: Bureau of Economic Analysis via Haver Analytics.

Gross domestic product

Gross domestic income

1

+

_

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

Percent, annual rate

20232022202120202019201820172016

19. Change in real personal consumption expenditures

H1

H2

S

OURCE

: Bureau of Economic Analysis via Haver Analytics.

MONETARY POLICY REPORT: MARCH 2024 17

of tight nancial conditions was supported

by the strong labor market and rising real

incomes. Indeed, after declining, on average,

in 2021 and 2022, real disposable personal

income increased robustly last year. However,

last year’s spending was also accompanied by

households drawing down their liquid assets,

such as checking accounts, and by relying

more on credit. Indeed, the saving rate was

3.9percent in the fourth quarter of 2023,

well below pre-pandemic levels (gure20). In

addition, although household wealth relative

to income remains high in the aggregate, it has

declined, on net, since the end of 2021 and so

is likely providing less support to consumer

spending. Consumer spending since the

pandemic has been more robust than measures

of consumer sentiment would suggest.

Although sentiment in the Michigan survey

has improved markedly in recent months, it

remains much further below its pre-pandemic

level than does a similar measure from the

Conference Board, which puts more weight on

labor market conditions (gure21).

Consumer nancing conditions tightened

last year

Credit remains available for most consumers,

though interest rates on both credit cards

and auto loans remain higher than the levels

observed in 2018 at the peak of the previous

monetary policy tightening cycle. Indeed,

interest rates on credit cards have continued

to increase since the rst half of last year. In

addition, banks reported continued tightening

of lending standards across consumer

credit products, in part reecting lenders’

concerns about further deterioration in

credit performance and higher funding costs.

Delinquency rates for credit cards rose further

over the second half of 2023, while those for

auto loans attened out; both rates are notably

above levels observed just before the pandemic.

Reecting these and other factors, consumer

credit expanded moderately during the second

half of last year, driven by robust growth in

credit card balances and modest growth in

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

PercentMonthly

2023202220212020201920182017201620152014

20. Personal saving rate

NOTE: The data extend through December 2023.

S

OURCE

: Bureau of Economic Analysis via Haver Analytics.

Michigan survey

50

60

70

80

90

100

110

February 1966 = 100

25

45

65

85

105

125

145

2024202220202018201620142012201020082006

1985 average = 100

21. Indexes of consumer sentiment

Conference Board

N

OTE: The data are monthly and extend through February 2024. The

February data for the Michigan survey are preliminary.

S

OURCE: University of Michigan Surveys of Consumers; Conference

Board.

18 PART 1: RECENT ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL DEVELOPMENTS

auto loans (gure22). In contrast, student

loan balances fell in the second half of last

year, in large part driven by the cancellation

of debt for certain borrowers in income-driven

repayment plans.

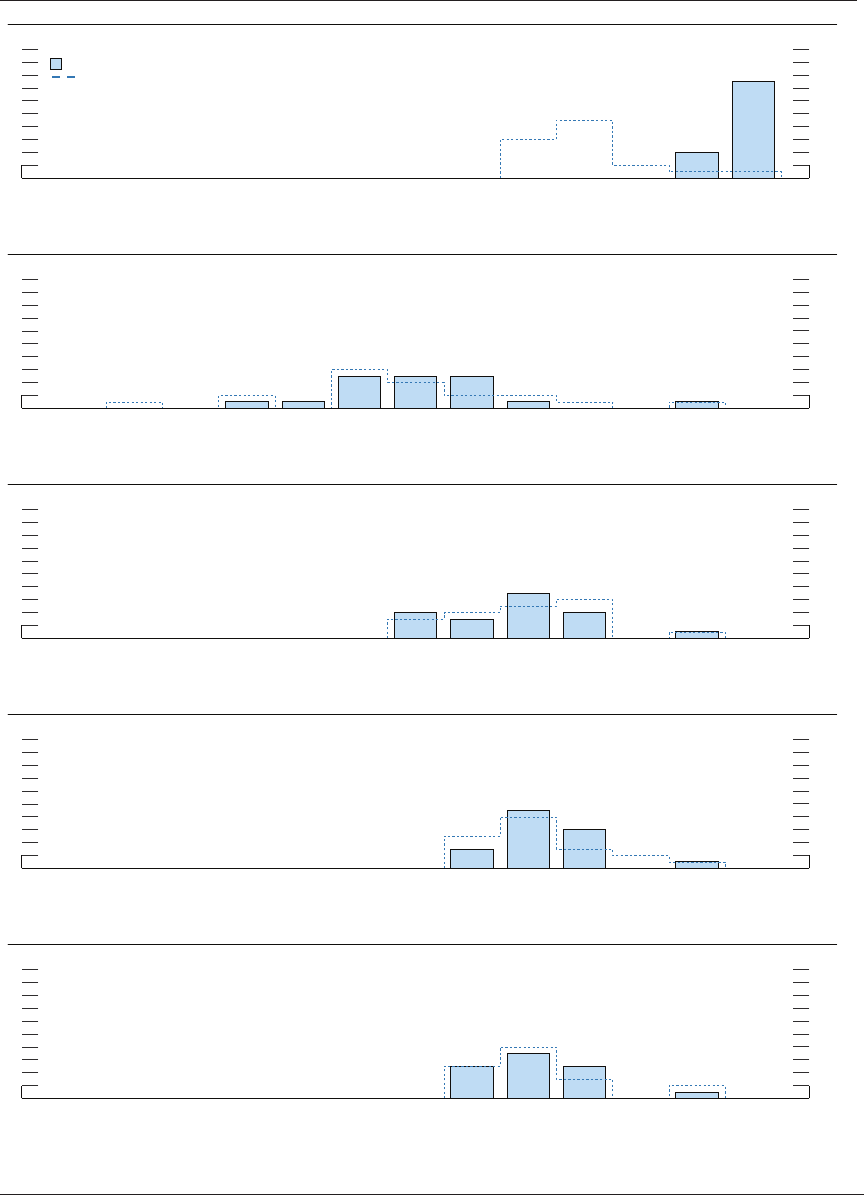

Residential investment turned around and

grew modestly in the second half of 2023

After declining steeply in 2022 on the heels of

the substantial rise in mortgage interest rates,

residential investment fell a bit further in the

rst half of 2023 but picked up in the second

half of the year. The pickup in housing activity

since mid-2023 masked some important

dierences across components of the market,

with sales of existing homes much weaker than

sales of new homes and with construction of

single-family homes remaining relatively solid

while multifamily construction declined. (The

box “Recent Housing Market Developments”

provides further discussion.)

Capital spending growth softened amid

tighter nancial conditions and subdued

sentiment

Tighter nancial conditions and downbeat

business sentiment led to a slowdown in

business investment spending growth in the

second half of 2023 (gure23). Equipment

investment spending declined in the second

half of the year, while investment in

intellectual property products—which include

software and research and development—

continued to decelerate from its solid pace

of growth over the previous few years.

Investment in nonresidential structures, which

had surged in early 2023 because of a boom

in manufacturing construction—especially

for factories that produce semiconductors or

electric vehicle batteries—also decelerated in

the second half of 2023, although the level of

structures investment remained much higher

than in previous years. Although indicators

of business sentiment and prot expectations

have improved in recent months, sentiment

remains subdued.

15

10

5

+

_

0

5

10

15

20

25

Percent, annual rate

20232022202120202019201820172016

23. Change in real business xed investment

H1

H2

N

OTE

: Business xed investment is known as “private nonresidential

xed investment” in the national income and product accounts. The

key

identies bars in order from left to right. Equipment and intangible

capital investment was little changed in 2023:H2.

S

OURCE

: Bureau of Economic Analysis via Haver Analytics.

Structures

Equipment and intangible capital

10

5

+

_

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

Billions of dollars, monthly rate

2023202220212020201920182017201620152014

22. Consumer credit ows

H1

H2

N

OTE

: Student loan balances were little changed in 2023:H1.

S

OURCE

: Federal Reserve Board, Statistical Release G.19, “

Consumer

Credit.”

Student loans

Auto loans

Credit cards

MONETARY POLICY REPORT: MARCH 2024 19

However, several other factors have supported

underlying demand for housing, somewhat limiting

the effect of higher mortgage rates. First, the labor

market has remained strong, with historically low

unemployment and real wage growth turning positive

last year. Second, households may still be gradually

adjusting to long-term remote or hybrid work exibility

by seeking additional space. Third, a rising fraction of

buyers have been able to purchase homes with cash

rather than taking out mortgages. The share of homes

purchased with cash was about 15percent in 2020 and

increased to about 25percent in 2023, with the drop in

home sales concentrated in mortgage borrowers.

Housing supply has also faced constraints, due

to both short- and long-term factors. In the short

term, higher interest rates and tighter underwriting

by banks signi cantly increased builders’ costs of

nancing, discouraging new construction. In the long

term, despite a surge in construction in late 2020 and

2021, it appears that a variety of factors—including

zoning and other regulatory hurdles—have prevented

construction from keeping up with underlying demand,

resulting in a gross housing vacancy rate that is at a

historical low.

2

2. See Joseph Gyourko and Raven Molloy (2015),

“Chapter19—Regulation and Housing Supply,” Handbook of

Regional and Urban Economics, vol. 5, pp. 1289–337.

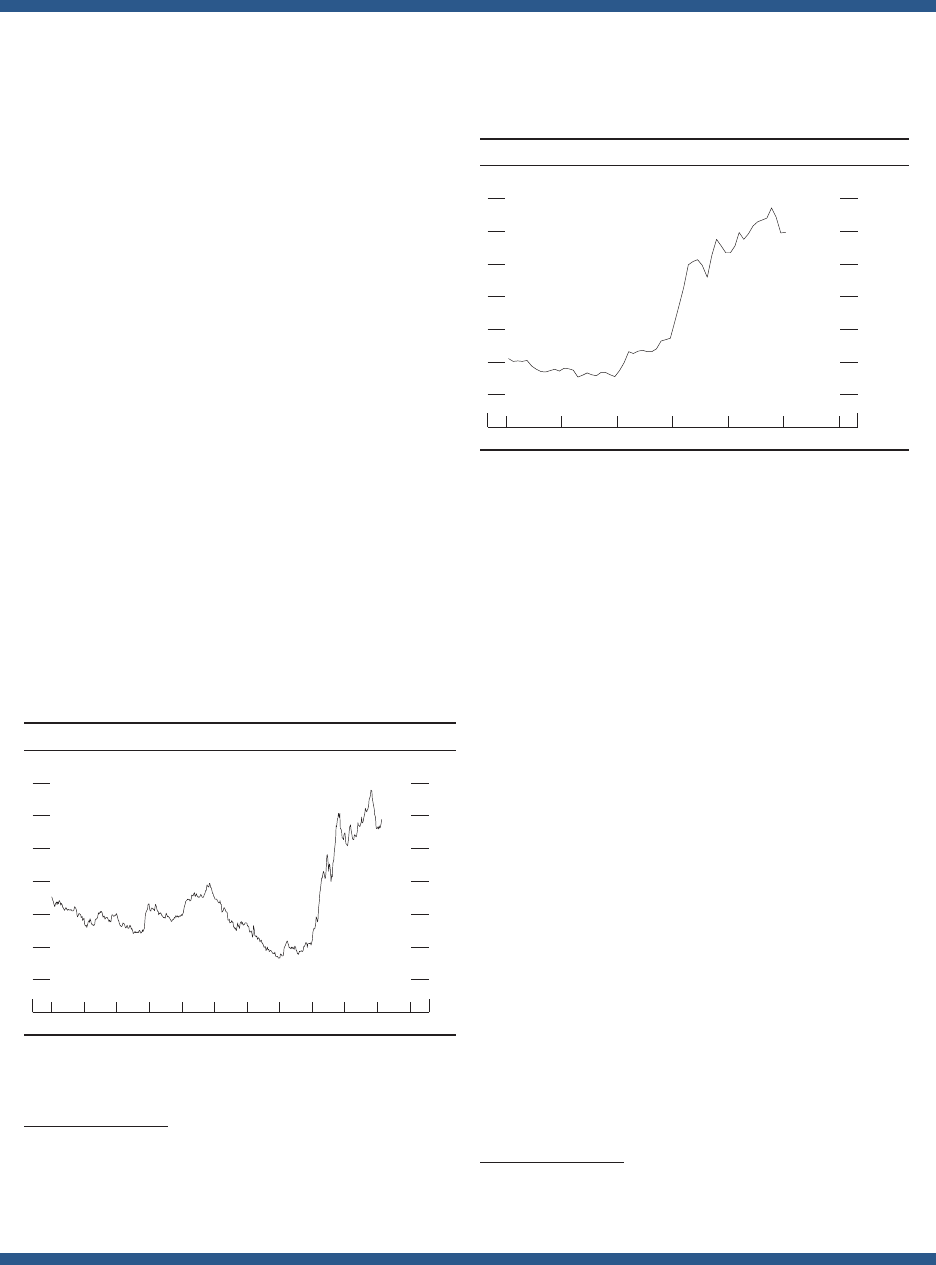

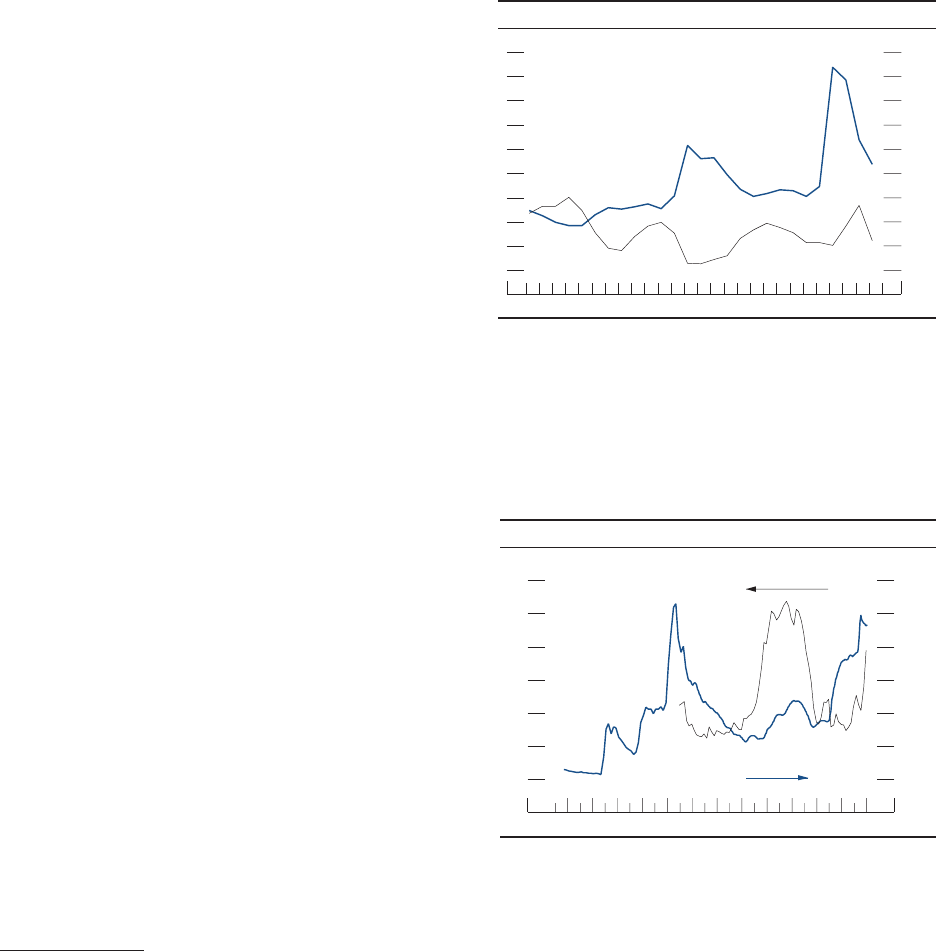

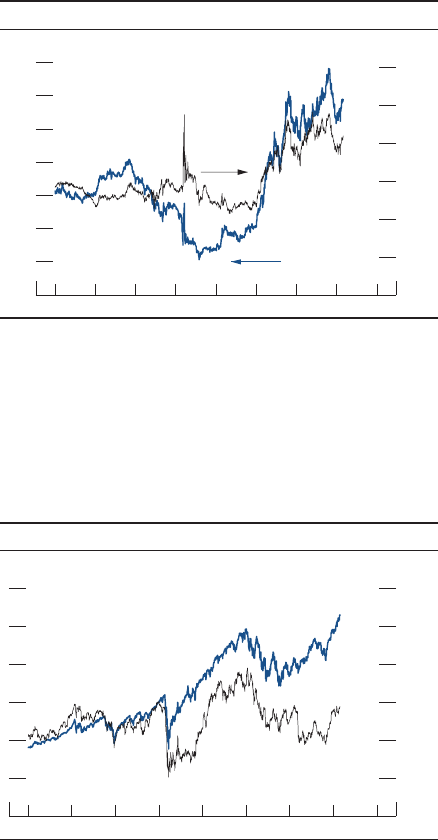

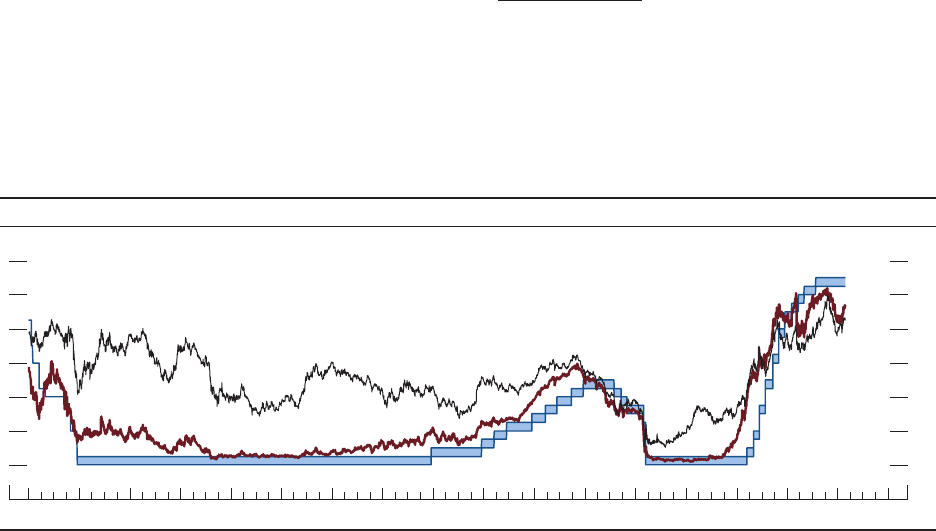

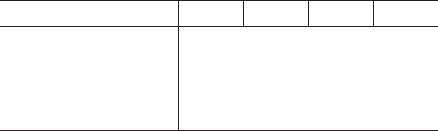

The rise in mortgage interest rates since early 2022

has reduced the overall demand for housing and

slowed activity in the housing sector appreciably.

The change in mortgage rates was unusually large

and rapid, with 30-year xed rates rising from about

3.2percent in January2022 to almost 8percent in

October2023, the highest level since 2000 ( gureA).

Although mortgage rates have declined somewhat

since October, they still averaged around 7percent in

February 2024.

The run-up in mortgage rates through late 2023,

combined with a further rise in house prices, resulted

in a sharp increase in typical mortgage payments and

has reduced housing demand and home sales. The

median monthly principal and interest payment on

newly originated home-purchase mortgages for owner-

occupied properties increased from below $1,400 in

January2022 to around $1,800 in early 2023 and has

remained around that elevated level ( gureB). As a

result, home sales (including both new and existing

properties) have fallen sharply over the past two years.

Home purchases by low-income households have

fallen disproportionately more, because mortgage

lenders impose maximums on the ratio of a borrower’s

debt service payments to the borrower’s income.

1

1. See Daniel Ringo (2022), “Declining Affordability and

Home Purchase Borrowing by Lower Income Households,”

FEDS Notes (Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal

Reserve System, July8), https://doi.org/10.17016/2380-

7172.3160.

Recent Housing Market Developments

(continued on next page)

1,000

1,200

1,400

1,600

1,800

2,000

2,200

Dollars

202420232022202120202019

B. Median monthly mortgage payments

Monthly

NOTE:The data shown are median monthly scheduled principal and

interest

payments on home purchase mortgages for owner-occupied

properties

by month of rate lock. The Optimal Blue data are aggregated

and

anonymized. The data do not contain lender or customer identities

or complete rate sheets.

S

OURCE

: Optimal Blue LLC, Optimal Blue Mortgage Price Data.

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

Percent

202420222020201820162014

A. Mortgage interest rates

Weekly

NOTE: The data are contract rates on 30-year, xed-rate

conventional

home mortgage commitments and extend through February 22, 2024.

SOURCE: Freddie Mac Primary Mortgage Market Survey via H

aver

Analytics.

20 PART 1: RECENT ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL DEVELOPMENTS

Recent Housing Market Developments (continued)

have interest rates below 4percent ( gureE). If these

homeowners with low mortgage rates want to move

to a different home with a new mortgage, their new

mortgage payment would be much higher. As a result,

many homeowners who might otherwise have moved

have instead opted to remain in their current home. The

net effect has been an unusually thin market for existing

homes, with a dramatic reduction in the number of

people both selling and bidding on homes. The decline

in the supply of existing homes for sale also makes it

dif cult for the remaining buyers in the market to nd

their preferred home and may be driving some to the

new home market even as overall sales are depressed.

New homebuilders have also been able to offer buyers

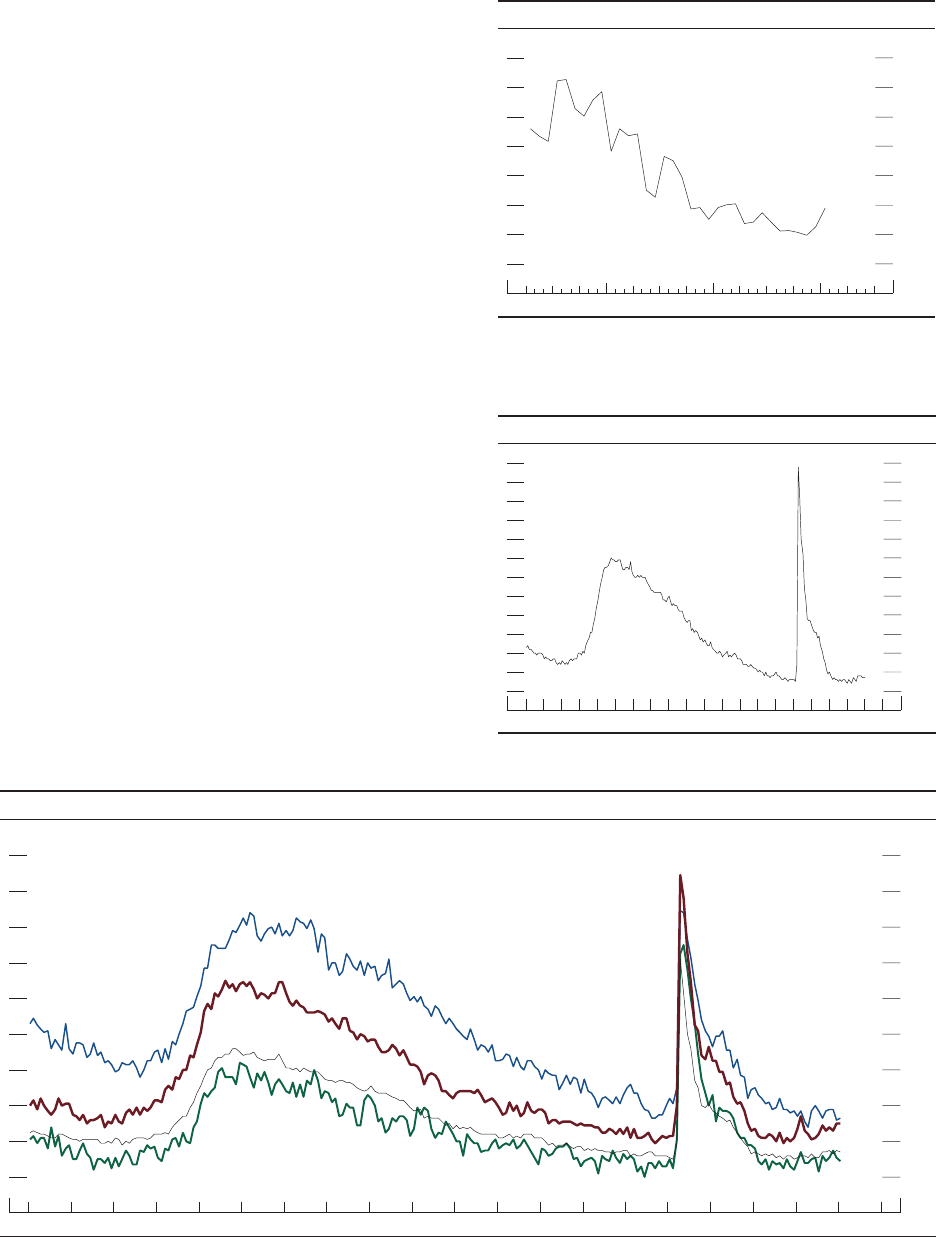

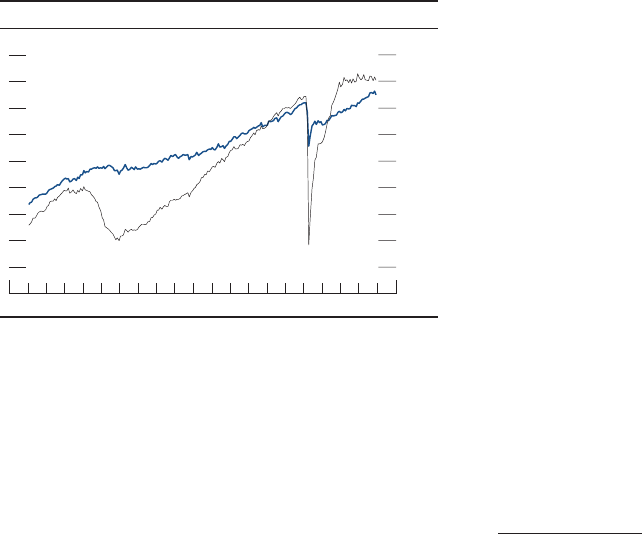

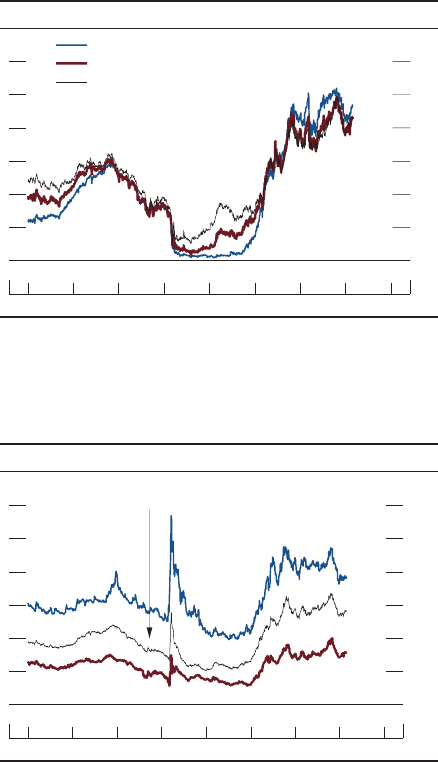

The recent performance of home prices re ects this

interplay between housing demand and supply. House

price growth slowed rapidly from its historically high

pace in response to the jump in interest rates, but it

has bounced back recently on a year-over-year basis,

leaving house price levels near record highs ( gureC).

The interplay between demand and supply has

played out quite differently across segments of the

housing market. In particular, the contrast between

the evolution of new and existing home sales has

been notable ( gureD). Many households purchased

homes or re nanced when xed mortgage rates were

at historically low levels in 2020 and 2021, and,

as a result, the majority of outstanding mortgages

(continued)

Zillow

CoreLogic

20

15

10

5

+

_

0

5

10

15

20

25

Percent change from year earlier

20242019201420092004199919941989

C. Growth rate in house prices

Monthly

N

OTE

: CoreLogic and S&P/Case-Shiller data extend through

December 2023.

S

OURCE

: CoreLogic, Inc., Home Price Index; Zillow, Inc., Real Estat

e

Data;

S&P/Case-Shiller U.S. National Home Price Index. The

S&P/Case-Shiller

index is a product of S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC

and/or

its aliates. (For Dow Jones Indices licensing information, see

the note on the Contents page.)

S&P/Case-Shiller

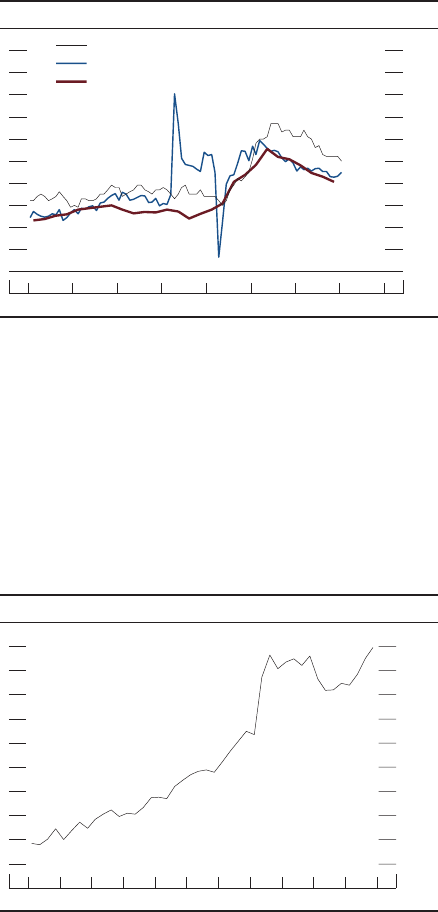

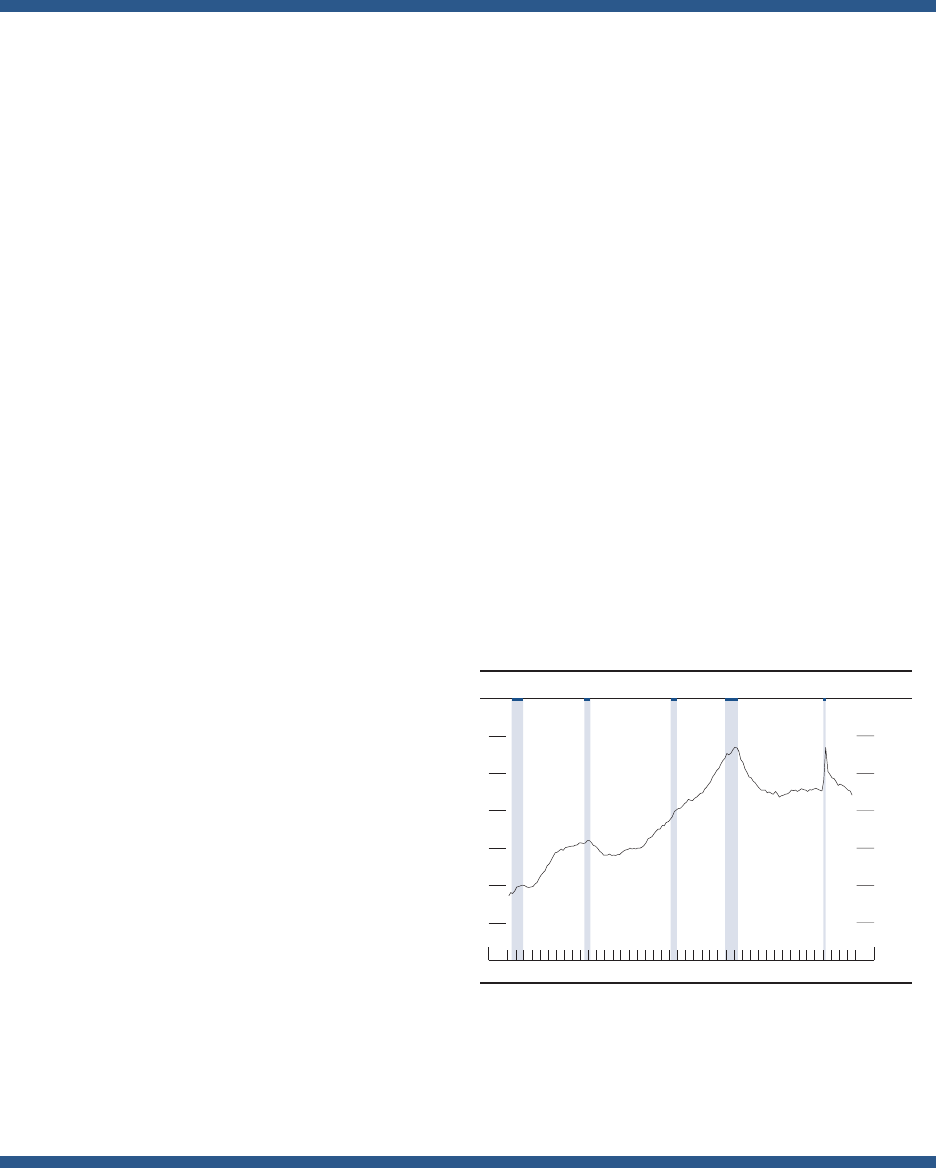

Existing home sales

3.0

3.5

4.0

4.5

5.0

5.5

6.0

Millions, annual rate

.2

.4

.6

.8

1.0

1.2

1.4

2024202220202018201620142012201020082006

D. New and existing home sales

Millions, annual rate

New home sales

N

OTE: The data are monthly. New and existing home sales

include

only single-family sales.

SOURCE: For new home sales, U.S. Census Bureau; for existing hom

e