Chowdhury, Anis

Working Paper

Growth oriented macroeconomic policies for small

islands economies: Lessons from Singapore

WIDER Research Paper, No. 2008/47

Provided in Cooperation with:

United Nations University (UNU), World Institute for Development Economics Research (WIDER)

Suggested Citation: Chowdhury, Anis (2008) : Growth oriented macroeconomic policies for

small islands economies: Lessons from Singapore, WIDER Research Paper, No. 2008/47, ISBN

978-92-9230-095-1, The United Nations University World Institute for Development Economics

Research (UNU-WIDER), Helsinki

This Version is available at:

https://hdl.handle.net/10419/45163

Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen:

Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen

Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden.

Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle

Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich

machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen.

Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen

(insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten,

gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort

genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte.

Terms of use:

Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your personal

and scholarly purposes.

You are not to copy documents for public or commercial purposes, to

exhibit the documents publicly, to make them publicly available on the

internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public.

If the documents have been made available under an Open Content

Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you may exercise

further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence.

Copyright © UNU-WIDER 2008

* University of Western Sydney, School of Economics and Finance, email: [email protected];

This is a revised version of a paper originally prepared for the UNU-WIDER conference on Fragile

States–Fragile Groups, directed by Mark McGillivray and Wim Naudé. The conference was jointly

organized by UNU-WIDER and UN-DESA, with a financial contribution from the Finnish Ministry for

Foreign Affairs.

UNU-WIDER gratefully acknowledges the contributions to its project on Fragility and Development

from the Australian Agency for International Development (AusAID), the Finnish Ministry for Foreign

Affairs, and the UK Department for International Development—DFID. Programme contributions are

also received from the governments of Denmark (Royal Ministry of Foreign Affairs), Norway (Royal

Ministry of Foreign Affairs) and Sweden (Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency—

Sida).

ISSN 1810-2611 ISBN 978-92-9230-095-1

Research Paper No. 2008/47

Growth Oriented Macroeconomic Policies

for Small Islands Economies

Lessons from Singapore

Anis Chowdhury*

April 2008

Abstract

Most small island economies or ‘microstates’ have distinctly different characteristics

from larger developing economies. They are more open and vulnerable to external and

environmental shocks, resulting in high output volatility. Most of them also suffer from

locational disadvantages. Although a few small island economies have succeeded in

generating sustained rapid growth and reducing poverty, most have dismal growth

performance, resulting in high unemployment and poverty. Although macroeconomic

policies play an important role in growth and poverty reduction, there has been very

little work on the issue for small island economies or microstates. Most work follows

the conventional framework and finds no or very little effectiveness of macroeconomic

…/.

Keywords: Caribbean, Pacific Islands, fiscal policy, small open economies

JEL classification: E5, E6, N1, O1

The World Institute for Development Economics Research (WIDER) was

established by the United Nations University (UNU) as its first research and

training centre and started work in Helsinki, Finland in 1985. The Institute

undertakes applied research and policy analysis on structural changes

affecting the developing and transitional economies, provides a forum for the

advocacy of policies leading to robust, equitable and environmentally

sustainable growth, and promotes capacity strengthening and training in the

field of economic and social policy making. Work is carried out by staff

researchers and visiting scholars in Helsinki and through networks of

collaborating scholars and institutions around the world.

www.wider.unu.edu [email protected]

UNU World Institute for Development Economics Research (UNU-WIDER)

Katajanokanlaituri 6 B, 00160 Helsinki, Finland

Typescript prepared by Liisa Roponen at UNU-WIDER

The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s). Publication does not imply

endorsement by the Institute or the United Nations University, nor by the programme/project sponsors, of

any of the views expressed.

policies in stabilization. They also concentrate on short-run macroeconomic

management with a focus almost entirely on either price stability or external balance.

The presumption is that price stability and external balance are prerequisite for

sustained rapid growth. This paper aims to provide a critical survey of the extant

literature on macroeconomic policies for small island economies in light of the available

evidence on their growth performance. Given the high output volatility and its impact

on poverty, this paper will argue for a balance between price and output stabilization

goals of macroeconomic policy mix. Drawing on the highly successful experience of

Singapore, it will also outline a framework for growth promoting, pro-poor

macroeconomic policies for small island economies/microstates.

Acronyms

AD aggregate demand

CPF Central Provident Fund

ECCU Eastern Caribbean Currency Union

GLCs government linked companies

HDI human development index

IMF International Monetary Fund

SMEs smaller and medium size enterprises

1

1 Introduction

One characteristic that small island economies share is vulnerability. This arises from a

number of factors, such as small size, remoteness, proneness to natural disasters, and

environmental fragility (see Briguglio 1995; Atkins, Mazzi and Easter 2000). They are

also very open economies with a high trade-GDP ratio, but their export base is very

narrow, dominated by primary products and natural resources. They are largely

dependent on external financial assistance, and their financial sector is extremely

shallow. Thus, small island economies are subject to external disturbances from the

world goods and financial markets. As a result, small island economies experience

significant volatility in their economic growth.

While most observers believe that small island economies are structurally

disadvantaged, some hold the view that they also have advantages. Kuznets (1960), for

example, notes the advantage of a small and more cohesive population which allows

them to adapt better to change. Easterly and Kraay (2000) argue that the growth

advantages of openness (trade and investment) outweigh the disadvantages in terms of

trade volatility, and hence, small states do not necessarily have a poorer economic

performance than larger countries.

1

Nevertheless, real per capita GDP growth tends to

be much more volatile in smaller economies than in larger ones, and there is a growing

consensus that high output or growth volatility adversely affects the poor. That is, the

poor are more vulnerable to shocks and macroeconomic volatilities (see de Ferranti

et al. 2000; World Bank 2000). The poor have less human capital to adapt to downturns

in labour markets. They have less assets and access to credit to facilitate consumption

smoothing. There may be irreversible losses in nutrition and educational levels if there are

no appropriate safety nets, as is usually the case in most developing countries. The World

Development Report 2000/2001 (World Bank 2000) finds an asymmetric behaviour of

poverty levels during deep cycles: poverty levels increase sharply in deep recessions and

do not come back to previous levels as output recovers.

2

This is an important observation in light of the orthodox macroeconomic policy package

designed by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) since the early 1980s. The focus of

such policies has been almost entirely on either price stability or external balance. The

presumption is that price stability and external balance are prerequisites for sustained

rapid growth. Using the macroeconomic experience of the Caribbean and Pacific Island

economies, this paper will argue for a balance between price and output stabilization goals

of macroeconomic policy mix. This paper also takes a contrary view to the conventional

wisdom that small open island economies do not have much control over their

macroeconomic instruments. The experience of Singapore shows that an island economy

can successfully stabilize both the employment and price levels by adopting innovative

1

In a cross-country regression with 157 countries, Easterly and Kraay (2000) find that: ‘microstates are

50 per cent richer than other states, controlling for location’. In a sample of 48 countries, Milner and

Westaway (1993) find no significant evidence of the effect of country size on economic growth. Also,

Armstrong et al. (1998) find in their cross-country regressions no significant effect of population size

on economic growth. Srinivasan (1986) and Streeten (1993) argue that small may be beautiful.

Singapore and Hong Kong are examples of two highly successful yet small economies.

2

Scatter plots of a large number of cross-country data reveal that the variability of nominal GDP

growth has a negative correlation with the growth of the average income of the poorest fifth of the

population, and a positive correlation with inequality (measured by the Gini coefficient). See

Chowdhury (2006). Also see Glewwe and Hall (1998).

2

macroeconomic policy-mixes. Drawing on Singapore experience, this paper will outline a

framework for growth promoting, pro-poor macroeconomic policies for small island

economies/microstates.

2 Economic characteristics of Caribbean and Pacific Island economies

Table 1 listx basic socioeconomic indicators of Caribbean and Pacific Island economies.

Table 2 lists their vulnerability index and output volatility index. As can be seen, despite

their smallness and high vulnerability, their real GDP per capita (in PPP terms) is

reasonably high when compared with larger developing countries. A number of Caribbean

Island economies also have a high human development index (HDI), while the rest are

ranked as medium human development countries. Analysing the relative performance of

Table 1

Size and socioeconomic indicators of the Caribbean and Pacific Island economies, 2003

Economy

Area

(thousands km

2

)

Population

(thousands)

Real GDP per

capita (PPP$) HDI

Caribbean Island states (2003)

Antigua & Barbuda

Bahamas

Barbados

Belize

Dominica

Dominican Repubic

Grenada

Guyana

Haiti

Jamaica

St Kitts & Nevis

St Lucia

St Vincent & the Grenadines

Suriname

Trinidad & Tobago

0.44

14.0

0.43

23.0

0.75

0.34

216.0

11.0

0.27

0.62

0.39

164.0

0.44

74

312

272

290

72

102

762

2,600

50

167

112

439

1,300

5,469

17,012

15,494

5,606

5,880

6,033

7,580

3,963

1,467

3,639

12,510

5,703

5,555

3,799

8,964

0.800

0.826

0.871

0.784

0.779

0.727

0.747

0.708

0.471

0.742

0.814

0.772

0.733

0.756

0.805

Pacific Island states (2003)

Cook Islands

Federated States of Micronesia

Fiji

Kiribati

Marshall Islands

Nauru

Palau

PNG

Samoa

Solomon Islands

Tonga

Tuvalu

Vanuatu

0.24

0.70

18.27

0.69

0.18

0.02

462.24

2.94

27.56

0.75

0.03

12.19

na

19

810

100

200

na

52

589

169

442

100

10

91

na

na

4,668

1,475*

1,970*

na

na

2,280

5,041

1,648

3,740*

na

2,808

na

na

0.758

na

na

na

0.535

0.65

0.622

na

na

0.542

Note: * = 1999.

Source: World Bank (2000); UNDP (various years).

3

Table 2

Composite vulnerability and output volatility index of Caribbean and Pacific Island economies

Composite vulnerability Output volatility

Index Rank Index Rank

Caribbean Islands

Antigua & Barbuda

Bahamas

Barbados

Belize

Dominica

Dominican Repub.

Grenada

Guyana

Haiti

Jamaica

St. Kitts & Nevis

St. Lucia

St. Vincent & the Grenadines

Suriname

Trinidad & Tobago

10.621

10.368

5.780

6.854

8.138

4.680

8.232

7.976

4.366

7.426

6.388

7.469

4.736

5.055

5.358

2

4

38

25

15

91

14

16

97

19

29

18

89

60

49

13.38

7.37

4.34

9.63

6.12

5.52

6.89

11.87

5.86

3.43

5.97

6.59

6.08

7.56

8.75

2

24

73

14

40

54

30

4

51

90

49

34

42

23

17

Pacific Islands

Fiji

PNG

Samoa

Solomon Islands

Tonga

Vanuatu

9.034

6.182

7.345

8.389

10.470

13.343

9

31

20

11

3

1

6.84

5.03

6.92

11.21

13.18

3.61

31

64

29

8

3

89

Note: Rank amongst 110 developing and island states.

Source: Commonwealth Secretariat (2000).

small island developing economies, Lino Briguglio (1995: 1622) wondered: ‘whether

the economic fragilities of small island developing economies are actually the reason for

their relatively high GDP per capita and human development index’.

The high real per capita income and HDI may, therefore, give an impression that

poverty in the Caribbean and Pacific Islands is not as acute as in other countries.

However, surveys of living conditions conducted between 1996 and 2002 in the

Caribbean reveal a very different picture. These surveys used poverty measures in terms

of the ability to buy a basic consumption basket of food and non-food items, such as

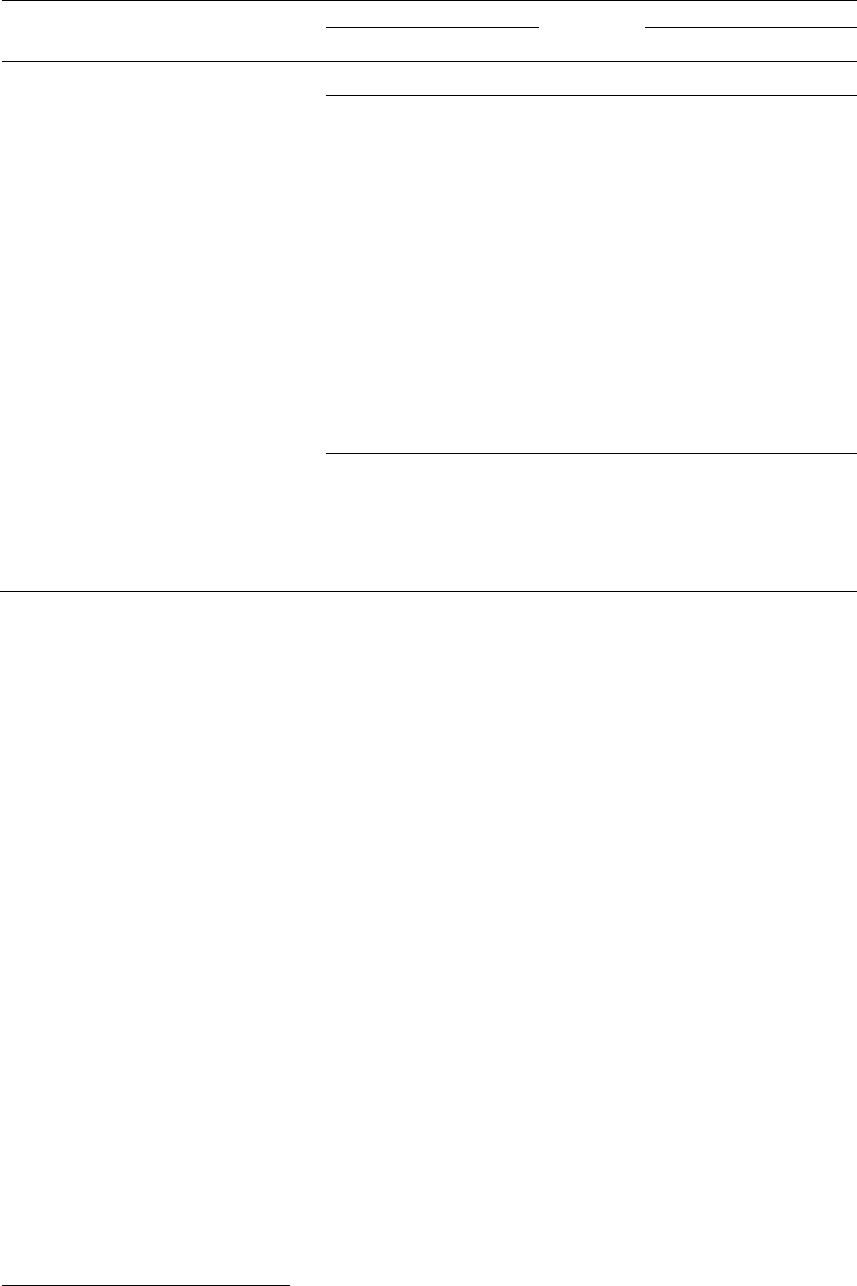

education, housing and transportation. According to these surveys (see Figure 1), Haiti

and Suriname are at the high end of the spectrum with an estimated poverty incidence of

65 per cent and 63 per cent, respectively. Clustered in the 30-40 per cent range are

Belize, Dominica, Grenada, Guyana, St Kitts and Nevis, and St Vincent and the

Grenadines. The estimated poverty rates in Anguilla, St Lucia and Trinidad and Tobago

range between 20 per cent and 29 per cent, while they are 14 per cent and 20 per cent,

respectively in Barbados and Jamaica.

3

The quality of life is equally dismal in the Pacific Islands. For example, in Papua New

Guinea (PNG) and Vanuatu 38-40 per cent of the population lives below the national

3

These figures are cited from Bourne (2005).

4

basic needs poverty line,

4

and about 61 per cent do not have access to safe water. While

58 per cent of children are receiving education in Vanuatu, the figure is only 41 per cent

in PNG. In Fiji, the percentage of the population living below the national basic poverty

line in Fiji is 25 per cent, and 53 per cent of the population do not have access to safe

water. The poverty rate in Samoa is about 20 per cent, and in the Solomon Islands only

52 per cent of children are enrolled in education.

What is more disturbing is the vulnerability of the population to poverty. For example,

in Jamaica the poverty rate goes up from 3.2 per cent to 25.2 per cent when the

international poverty line moves from $1-a-day to $2-a-day. In Dominican Republic, the

poverty rate jumps from 3.2 per cent to 16.0 per cent, and in Trinidad and Tobago, it

rises from 12.4 per cent to 39.0 per cent with the upward adjustment of the international

poverty line.

5

This means a large number of people live just above the poverty line, and

any sustained adverse shock to the economic can push them to poverty. Therefore, it is

important to analyse the sources of volatility in order to stabilize income and

employment growth at a high level.

Figure 1

Poverty rate, selected Caribbean and Pacific Island economies, per cent

Figure 1: Poverty Rate

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

B

a

rbados

Belize

Dom

i

nic

a

n Repu

b

Gre

nad

a

Guyana

Hai

t

i

J

a

maica

St.

K

i

t

ts

-

N

evi

s

St.

V

i

nce

nt-

G

r

e

n

d

Suri

na

me

Trinidad &

T

oba

g

o

Fi

j

i

PNG

Sam

o

a

V

anua

t

u

%

Source: Bourne (2005); Oxfam (2007); Abbot and Pollard (2004); UNDP (various years).

3 Macroeconomic performance and sources of volatility

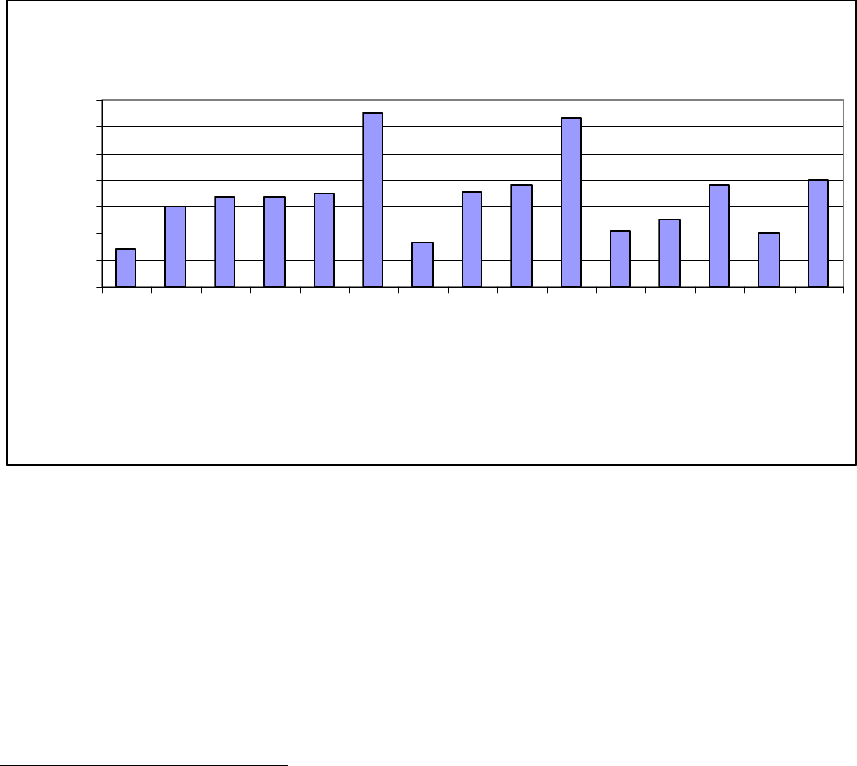

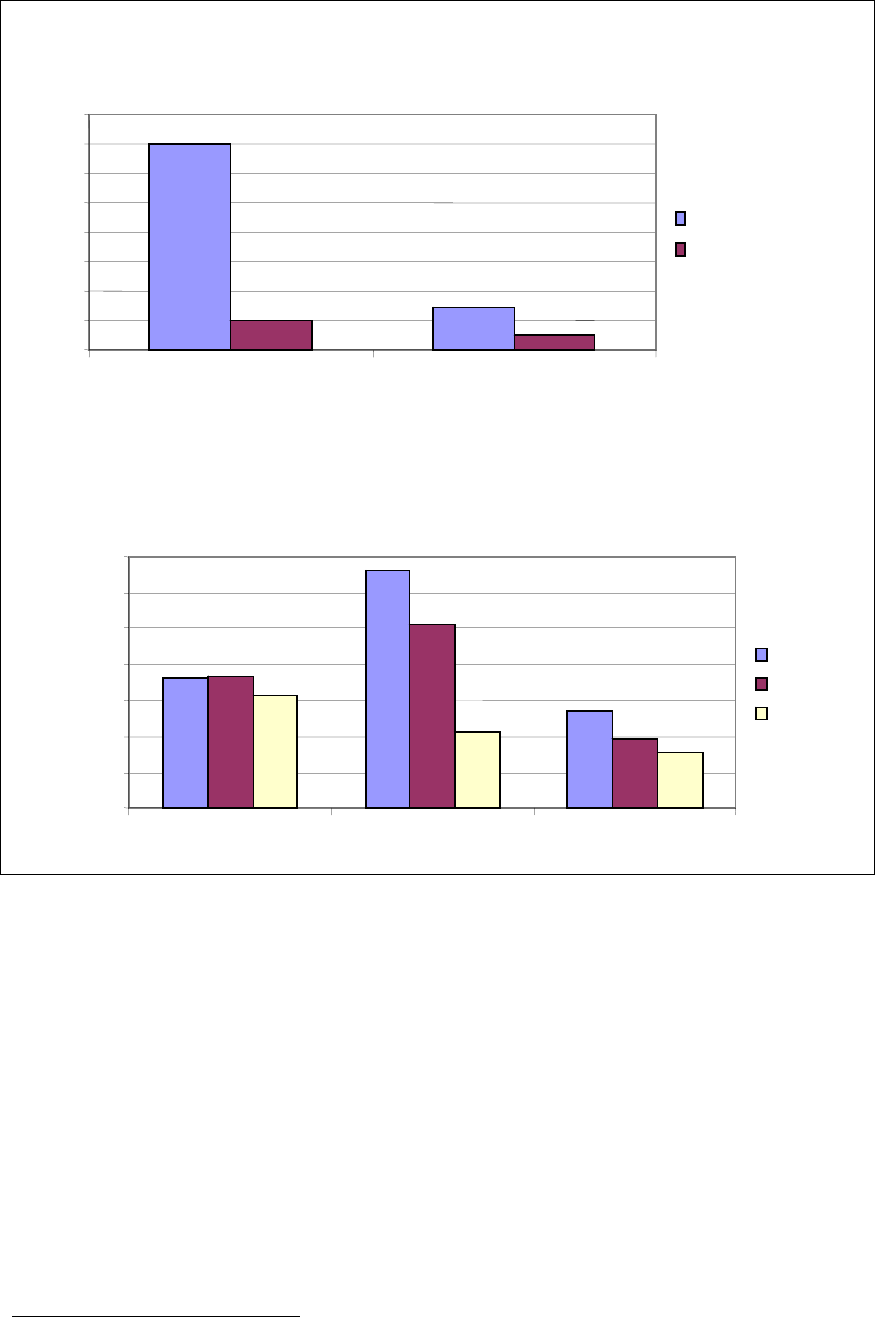

As can be seen from Panels A and B in Figure 2, extreme volatility is the hallmark of

both Caribbean and Pacific Islands, and for most, growth remains subdued, averaging at

less than 4 per cent. This is despite the fact that most have been quite successful in

containing the inflation rate at less than 4 per cent. This indicates that price stability or

4

National basic needs poverty line is a measure of the minimum income needed to buy sufficient food

and meet basic needs such as housing, clothing, transport, school fees, etc. (Oxfam 2007).

5

These figures are from UNDP (2002).

5

Figure 2

GDP growth in the Caribbean Islands and in the Pacific Islands

-6

-4

-2

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

16

1970s 1980s 1990s

2003 2004 2005

%

Antigua & Barb

Bahamas

Barbados

Belize

Dominica

Dominca Repub

Grenada

Guyana

Haiti

Jamaica

St. Kitts & Nevis

St. Luci

a

St. Vincent & Gren

Suriname

Trinidad & Tobago

-20

-15

-10

-5

0

5

10

15

20

25

1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005

%

Cook Islands

Fiji

Kiribati

PNG

Samoa

Solomon Islands

Tonga

Tuvalu

Vanuatu

Source: World Bank (2002b) and ECLAC (2006) for the Caribbean Islands, and ESCAP (2006) for the

Pacific Islands.

low inflation may be a necessary, but not a sufficient condition for sustained economic

growth.

6

Volatility of growth itself may affect growth, as economic instability tends to

skew investment towards short-run gains in a non-optimal way (Perry 2003).

6

Fichera (2006: 51), in reviewing the macroeconomic performance of the Pacific Islands and the

Eastern Caribbean Currency Union countries, remarks: ‘policies … although effective at maintaining

relative macroeconomic stability over 1995-2004, have not been effective at promoting growth.

Clearly, while macroeconomic stability is a necessary condition for growth, it is not sufficient’.

Panel A: CARIBBEAN ISLANDS

Panel B: PACIFIC ISLANDS

6

Importantly, economic volatility affects more adversely the employment and incomes of

less skilled workers, who do not have adequate coping mechanism. The absence of

publicly funded well-targeted safety nets accentuates the problem. Thus, in addition to

hard-core poor, a large number of people remain vulnerable to shocks to the economy.

Hence, macroeconomic policies should aim not just at price stability, but also at output

and employment stabilization, especially when shocks originate from the supply side.

7

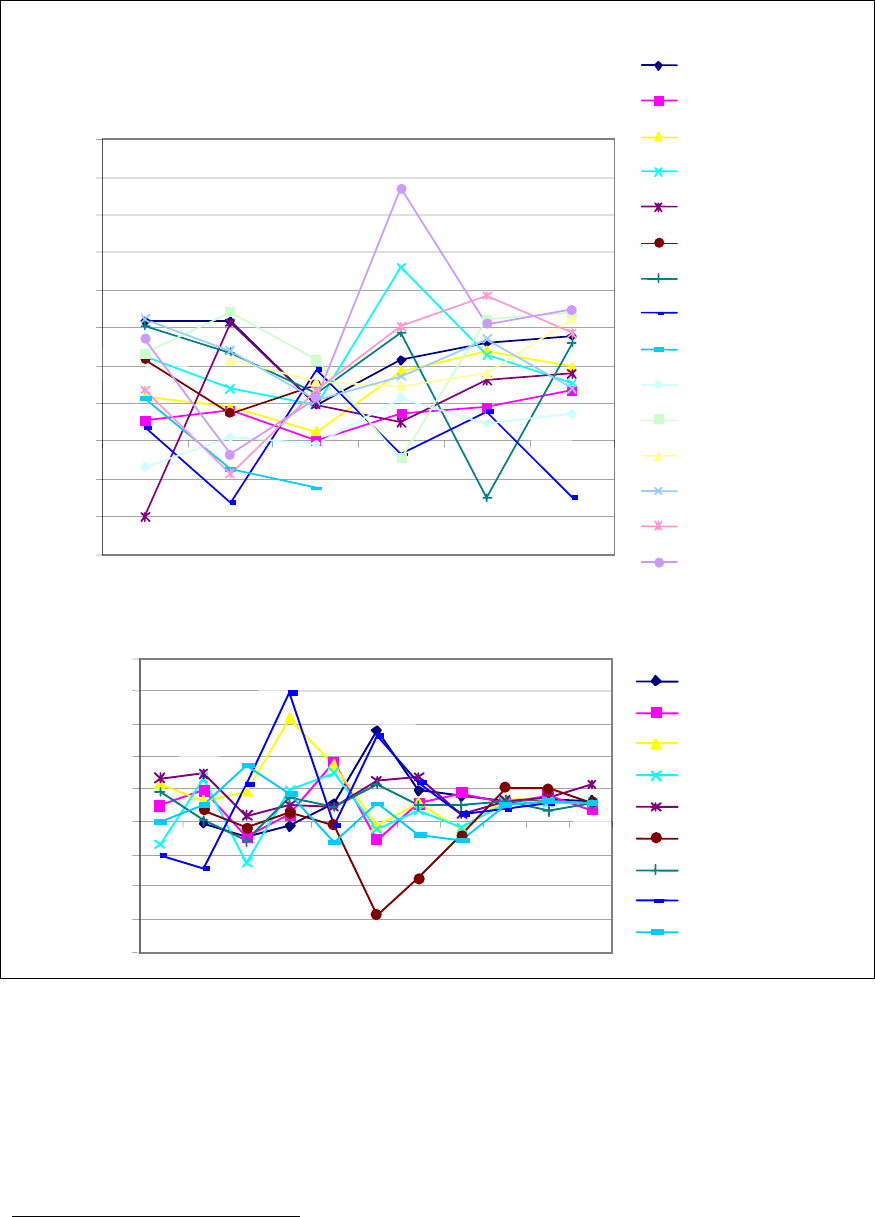

Figure 3

Inflation in the Caribbean Islands and the Pacific Islands

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

1970s 1980s 1990s

2003 2004 2005

%

Antigua & Barb

Bahamas

Barbados

Belize

Dominica

Dominca Repub

Grenada

Guyana

Haiti

Jamaica

St Kitts & Nevis

St Luci

a

St Vincent & Gren

Suriname

Trinidad & Toba

g

o

-5

0

5

10

15

20

1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005

%

Cook Islands

Fiji

Kiribati

PNG

Samoa

Solomon Islands

Tonga

Tuvalu

Vanuatu

Source: World Bank (2002b) and ECLAC (2006) for the Caribbean Islands, and ESCAP (2006) for the

Pacific Islands.

7

Interestingly, contrary to what has become known as the so-called ‘Washington consensus’ as pursued

by the IFIs that aimed solely on stabilizing the nominal variables (e.g., inflation), the originator of the

Washington consensus, John Williamson did include the need to stabilize the real economy a la

Keynes in his list of ‘good policies’. See Williamson (2004).

Panel A: CARIBBEAN ISLANDS

Panel B: PACIFIC ISLANDS

7

Figure 4A

Frequency (per year) and costs of natural disasters, 1970-2000

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

16

Caribbean median Pacific median

Peak cost/GDP

Frequency

Source: World Bank (2002a).

Figure 4B

Volatility in terms of trade

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

Caribbean Pacific Islands Singapore & Hong Kon

g

Median standard deviatio

n

1970s

1980s

1990s

Note: Terms-of-trade shocks are defined as (trade/GDP)x(change in terms of trade).

Source: World Bank (2002a).

It is well accepted that the island economies are particularly prone to natural disasters

(Figure 4A). As Figure 4B shows, Caribbean and Pacific Island economies have also

suffered larger terms of trade shocks than two successful island economies, Singapore

and Hong Kong. A relatively favourable disposition certainly has played a role in

Singapore and Hong Kong’s better macroeconomic and growth performance.

Nonetheless, their economic condition was not hugely different in the 1950s and 1960s

from the Caribbean and Pacific Islands, with widespread unemployment and poverty.

8

Economic policies and the activism of the government, especially in Singapore, have

been largely responsible for the turnaround in their fortunes. In addition, both Singapore

and Hong Kong are better able to absorb shocks due to the depth of their financial

sector.

8

Singapore’s poverty rate was nearly 25 per cent in the mid-1950s, and even in 1970, the

unemployment rate was over 8 per cent.

8

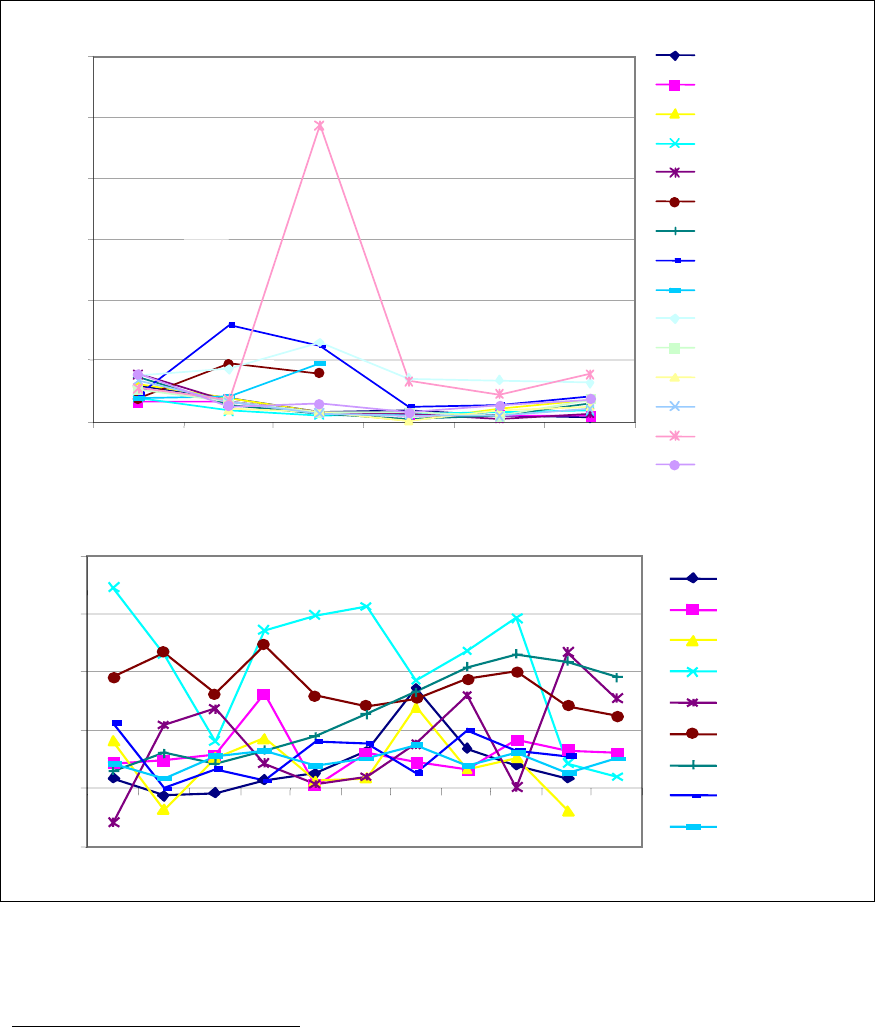

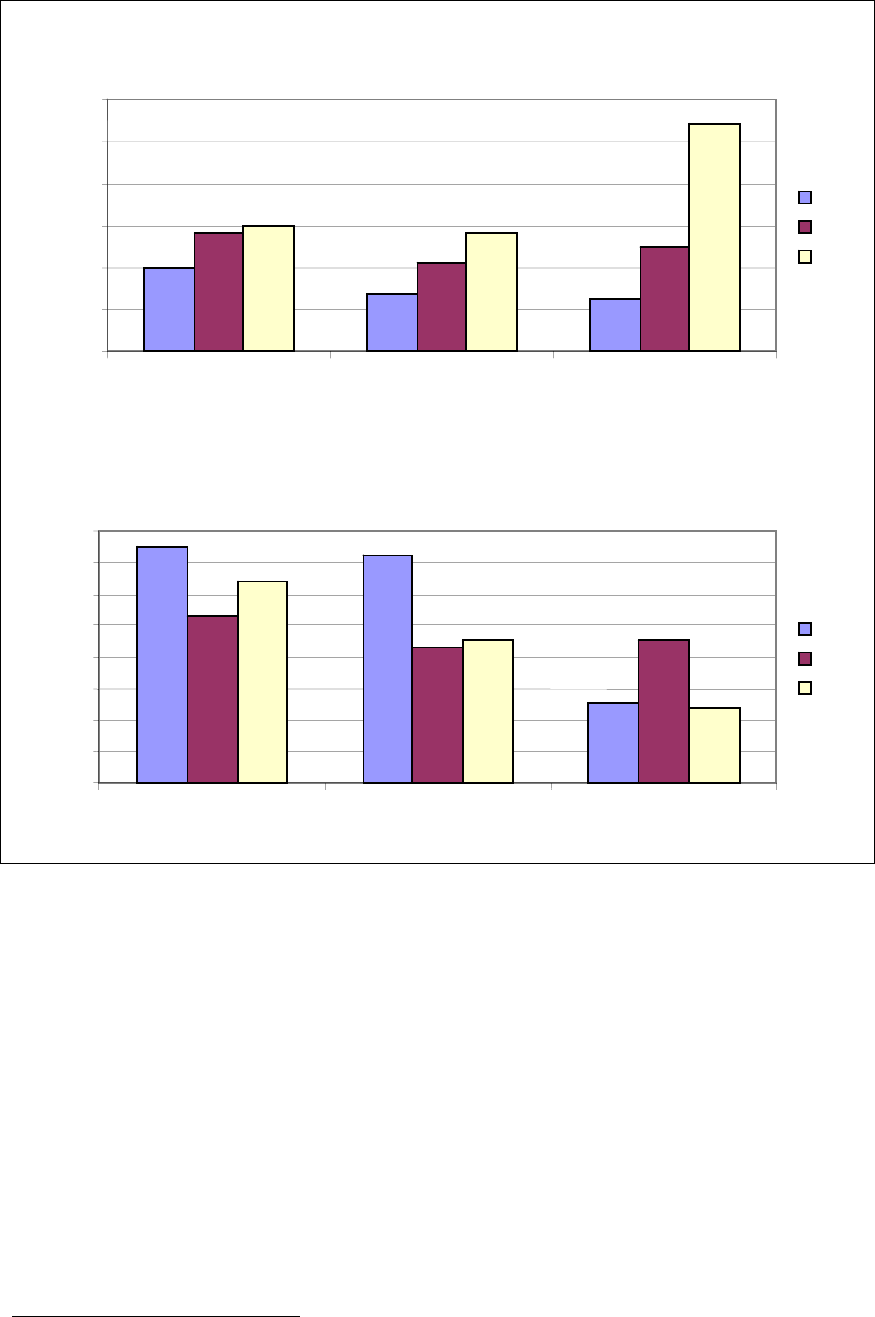

While the island economies are subjected to mostly adverse supply shocks, nearly all of

them followed conservative macroeconomic policies, as required by their adjustment

package with the IMF.

9

This is evident from Figure 5A, which shows the growth rates

of domestic credit to the private sector. As can be seen, domestic credit grew at a much

faster rate in Singapore and Hong Kong. In the case of the Caribbean countries,

domestic credit to the private sector remained more or less stagnant since the 1980s.

That is, the monetary policy stance in these countries has been by and large

contractionary.

There is a consensus that fiscal policy in most poor countries with a weak revenue base

tends to be procyclical.

10

Government revenue in the small Caribbean and Pacific

Island economies depends excessively on trade taxes and foreign aid. Thus, trade shocks

and aid volatility are a major source of instability in government revenue. If foreign aid

flows do not match the loss of revenue during adverse shocks, governments are forced

to cut investment expenditure, since it is politically difficult to cut the non-development

expenditure, such as civil servant salaries or various subsidies and welfare programs.

This exacerbates the impact of shocks, as well as harms the long-term growth potential.

This kind of adjustment was observed particularly in the Pacific Island economies,

where development expenditure which was already too low as a percentage of public

spending. However, there have been some differences in the fiscal policy response of

the Eastern Caribbean Currency Union (ECCU) governments. They:

dedicated a large share of their spending to public investment,

particularly during the 1980s, when external assistance was abundant. In

the late 1990s and early 2000s, these countries raised public spending,

including for investment, trying to offset exogenous shocks on growth

and declining private investment (Fichera 2006: 50-1).

As a result, the ECCU countries grew at a faster rate. Even the worst performing ECCU

country experienced positive growth (2.5 per cent on average) in per capita income

during 1995-2004.

Figure 5B shows that public consumption growth has been highly volatile in both

Caribbean and Pacific Island economies. Perry (2003) finds that fiscal volatility

accounts for 15 per cent among the causes of excess volatility in Latin America and the

Caribbean. This excessive volatility in the growth of public consumption is largely due

to boom-bust nature of the revenue, and results in procyclical fiscal policy. Thus, one

can reasonably conclude that procyclical fiscal policy and tighter monetary policy

aimed solely at price stability in the wake of exogenous supply shocks exacerbated the

impacts of shocks.

11

This brings us to the critical issue of the role of macroeconomic

policies.

9

See Worrell (1987) for the experience of Caribbean economies. For the Pacific Islands experience, see

Siwatibau (1993).

10

Eslava (2006) surveys the literature on the determinants of procyclicality of fiscal policy. Also see

Gavin et al. (1996) for the Latin American and Caribbean context.

11

ECLAC (2006: 36) in its Survey of Latin America and the Caribbean, 1999-2000 comments: ‘The

priority given … to fighting inflation and restoring credibility of stabilization policies had given a

procyclical bias to macroeconomic policy…’.

9

Figure 5A

Domestic credit to the private sector, % of GDP

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

Caribbean Pacific Islands Singapore & Hong Kong

% GDP (Regional medians)

1970s

1980s

1990s

Figure 5B

Volatility of public consumption growth

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

16

Caribbean Pacific Islands Singapore & Hong Kong

Reginonal medians

1970s

1980s

1990s

Source: World Bank (2000).

The recent empirical growth literature shows that there is a strong negative correlation

between procyclical fiscal behaviour and the rate of long-term growth. On the other

hand, countercyclical fiscal policy enhances growth possibility by providing fiscal

reliefs (tax cuts and subsidies) to the struggling private sector during economic

downturns, as well as by boosting government investment in key economic and social

sectors.

12

The restrictive monetary and procyclical fiscal policy stance not only accentuates the

depth of economic contraction and harms long-term growth, but also has an

asymmetrically adverse impact on the poor. To begin with, a tighter credit policy affects

small- and medium-size enterprises (SMEs), which depend mostly on bank financing,

more than it affects the larger firms. This has adverse employment impacts for the low-

skilled workers, as evidenced by the negative correlation between the volatility of

12

United Nations’ World Economic and Social Survey 2006 (chapter IV) provides a brief summary of

literature on the economic and social consequences procyclical macroeconomic policies.

10

nominal GDP and the income growth of the poor.

13

Studies also find that social

expenditures are kept at best constant as a percentage of GDP during downturns, and the

more targeted social expenditures tend to fall as a percentage of GDP, when they should

expand as the number of poor and unemployed increases.

14

4 Role of macroeconomic policies

4.1 Conventional macroeconomic models for small open economies

What role can macroeconomic policies play in very open small island economies?

Khatkhate and Short (1980) believe very little. According to them, the degree of

policymakers’ control over macroeconomic target variables (e.g., output, inflation and

external balance) is inversely proportional to the degree of openness of the product

market.

15

The fact that mini states are pricetakers in the international market, the

volume of exports, and therefore output, is determined by the mini state’s productive

capacity, which is influenced more by such factors as weather than macroeconomic

policies. Being at the same time highly import-dependent, their inflation is by and large

determined by their trading partners.

Corden (1984), on the other hand, using the example of Singapore, develops a model of

a small open economy where all products are tradable, and demonstrated that exchange

rates can be used to target inflation and wages policies to target competitiveness, and

hence, employment. Since the aggregate demand for output is perfectly price elastic,

domestic demand, and hence monetary policy and fiscal policy, do not have any direct

effects on the price level or employment.

16

To the extent that the monetary authority

pegs the exchange rate to a pre-determined level, money supply becomes endogenous.

Thus, monetary policy works only through its effects on the exchange rate. When the

exchange rate is allowed to float, perfect capital mobility renders fiscal policy

ineffective due to induced exchange rate effects.

17

13

See Chowdhury (2006).

14

See the World Bank study by de Ferranti et al. (2000).

15

‘by its [mini state’s] exposure to foreign trade such that the economic targets of its economy are

largely beyond its control’ Khatkhate and Short (1980: 1018). Caram (1989) holds a very similar

view: ‘Under the conditions now prevalent in small developing countries, it is not to be expected that

monetary financing and the ensuing increase in effective demand will result in an appreciable increase

in domestic production. The domestically generated supply of goods is insufficiently diversified and,

as a result of physical and organizational bottlenecks, has barely any short-term elasticity. Owing to

this and to the ample opportunities for imports, despite the exchange controls in force, the additional

demand will focus largely on the supply from abroad. The so-called monetary approach to the balance

of payments … proves to be highly topical for these countries’.

16

In an economy (closed or open) with a downward aggregate demand (AD), expansionary monetary

and fiscal policies work by raising the price level. Increased price level reduces real wage and hence

increases employment and output. But when an economy faces a perfectly price elastic AD, the

domestic price level cannot differ from the world price.

17

This follows from the standard Mundell-Fleming IS-LM-BP model with flexible exchange rates and

perfect capital mobility.

11

Treadgold (1992) provided a critique of Khatkhate and Short, and extended Corden’s

model to suit the conditions of small Pacific Island economies. To begin with, a number

of Caribbean and Pacific Island economies do not have separate currencies; they use

either US, Australian or New Zealand dollars. Thus, they cannot have the exchange rate

instrument as suggested by the Corden model, but they can still use wages policy for

employment target. Second, even for those economies which have their own currencies,

the assumption of perfect capital mobility is not relevant, as this would require perfect

substitutability between domestic and foreign bonds. However, even when the

assumption of perfect capital mobility is replaced with incomplete capital mobility,

Treadgold shows that under different labour market conditions, the policy implications

of the basic Corden model remain relevant. When money wages are inflexible

downward, the achievement of the employment target would require abandoning an

independent inflation target. That is, the exchange rate should be varied to achieve the

domestic inflation needed to reduce real wage for the employment target. On the other

hand, the downward real wage inflexibility excludes the possibility of achieving any

independent employment target, and macro policy (i.e., exchange rate policy) should be

directed to controlling the price level only. Finally, the microstates which experience a

high degree of labour mobility with larger economies essentially face a given real wage

determined in the larger economies. Their labour market mimics a competitive labour

market, and hence, employment is determined endogenously. As in the case of

downward real wage inflexibility, these microstates should use the exchange rate to

achieve the inflation target.

In sum, fiscal and monetary policies cannot play stabilizing roles in any of the three

theoretical models reviewed above. In the Corden model and its modified version, the

stabilization (price level and employment) role is assigned to the exchange rate and

wages policies. The fact that some Caribbean and Pacific Island economies could

successfully maintain very low inflation rates by using conventional demand

management policies proves Khatkhate and Short’s conclusion wrong. To the extent

that the effectiveness of policy instruments (exchange rates) in the Corden-Treadgold

framework depends on falling real wages, it does not offer much hope in economies

where poverty is high and real wage is at the subsistence level. In these countries, real

wage resistance does not have to be an outcome of a centralized wage-setting

mechanism and/or the nature labour market institutions. Real wage is already so low

that it cannot be reduced any further.

18

All three models focus on the demand-side role of fiscal and monetary policies and

ignore the fact that in developing countries, these policies are used predominantly for

economic growth and hence enhancing aggregate supply. Thus, employment creations

in these models imply movement along the labour demand curve (i.e., the reduction in

real wage). They also assume symmetry in both capital inflows and outflows, and

consider only short-term portfolio investment, not long-term foreign direct investment.

Most developing countries, especially the small Caribbean and Pacific Island

economies, do not attract much capital flows. As noted earlier, vulnerability risks

outweigh the expected gains from interest rate differentials, and they are more prone to

capital flights than capital inflows. For their long-term economic growth, they need

foreign direct investment and foreign aid, which are not sensitive to interest rate

differentials. Once these considerations are taken into account, fiscal and monetary

18

Lodewijks (1988) deals exhaustively with the limitations of real wage cuts in the context of PNG.

12

policies assume radically different roles from what can be derived from the Mundell-

Fleming model and its variants.

In particular, when the direct long-term (growth) and short-term (demand) aspects of

macroeconomic policies are juxtaposed or treated simultaneously, employment

creations do not depend on lower real wages (movement along the demand curve);

instead, employment is created by shifting the labour demand curve. That is, what is

needed in fragile economies such as Caribbean and Pacific Islands is state-led

development strategies.

4.2 Lessons from Singapore

The conventional wisdom is that Singapore pursues conservative macroeconomic

policies as is evident from its large foreign reserves and budget surpluses. However,

close observers of Singapore believe that the use of government budget surplus is a

misleading indicator of government’s fiscal stance due to the presence of various

statutory boards and a large public sector. By the mid-1980s, prior to the start of

privatization, there were about 490 government linked companies (GLCs) and 30

statutory boards which had substantial monopoly power. Government often used these

GLCs and statutory boards to pump-prime the economy whenever there was any sign of

economic downturns. These measures do not show up in the budget of the government.

Profits from GLCs and statutory boards subsidized deficits in government priority areas

like housing which kept up the effective demand. Thus, Toh (2005: 43) draws attention:

Far from non-intervention, the government believes in short-term

discretionary measures to even out adverse impacts caused by the

international business cycle and changing economic trends. Fiscal policy

is a key instrument for aggregate demand management.

In a rigorous study by using the IMF methodology of fiscal stance, Nadal-De Simone

(2000) notes that contrary to the common view, fiscal policy in Singapore during

1966-95 was not contractionary most of the time. Although the fiscal policy multiplier

is found to be small due to the openness of the economy, the government did not shy

away from using it, as it relied on the crowding-in factor of infrastructure and social

investment.

Fiscal policy in Singapore is used predominantly to promote non-inflationary economic

growth—supporting investment, entrepreneurship, and job creation. GLCs and statutory

boards were created since the late 1960s to jumpstart industrialization. The government

also owned the largest bank, Development Bank of Singapore. Huff (1995) notes that

government expenditure on infrastructure, accounting for 38 per cent of all gross capital

formation, played a large role in Singapore’s annual real GDP growth of 5.7 per cent

during the early phase (1960-66) of its development.

Singapore was able to undertake public sector investment in a massive scale without

incurring unsustainable debt and inflationary pressure due to its savings policy. There

are three aspects of its national savings policy. The first is the strict adherence to the

principle of achieving a surplus (or at least not run a deficit) in the current account of

the government. Second, the government followed the commercial principle of profit

generation for the GLCs and statutory bodies. Thus, primary budget surplus and profits

13

from GLCs and statutory boards contribute substantially to the public sector savings.

Finally, the scheme of compulsory contribution to the Central Provident Fund (CPF)

forces every employee to save. The combined contribution by both employees and

employers rose to 50 per cent of the payroll at its peak in the mid-1980s. These

measures raised national savings from about 12 per cent of GDP in 1965 to close to 45

per cent of GDP in 2004.

The CPF scheme has been instrumental for non-inflationary development financing.

First, the government could access a large pool of funds and did not have to borrow

from the monetary authority which is inflationary. Second, the compulsory contribution

to the CPF dampened demand pressure coming from public investment. It acted like an

automatic stabilizer for inflation. Critics argue that GLCs together with the public sector

crowd out private enterprise. However, there is little evidence of that in Singapore.

‘Every $1 increase over the preceding decade in public sector capital formation was

associated with an increase in private sector capital formation of $3 during the 1970s

and $2.8 for 1980-1992’ (Huff 1995: 747).

For Singapore, being highly dependent on external trade, management of the exchange

rate has been crucial. The Singapore dollar exchange rate is based on a managed float

system. The Monetary Author of Signapore manages the float within a target band

based on an undisclosed trade-weighted basket of the currencies of Singapore’s major

trading partners. Given the openness of Singapore with high import content, this seems

to be a very sensible policy, as contractionary monetary or interest rate policy can only

have limited effect on inflation, domestic inflation was kept low by allowing the

exchange rate to appreciate in line with foreign inflation (Huff 1995: 752). Furthermore,

reduction of the volatility of the exchange rate arising from exchange rate targeting may

reduce uncertainty and hence promote trade.

In order to retain some control on the monetary policy while following a managed

exchange rate, Singapore had a number of measures. They included withholding tax on

interest earned by non-residents on Singapore dollar holdings, preventing banks from

making Singapore dollar loans to non-residents or residents for use outside Singapore,

except to finance external trade. These amounted to restrictions on short-term capital

flows while Singapore always welcomed foreign direct investment.

Finally, Singapore used wages policy to complement its growth oriented fiscal and

monetary policies. Through the regulation of the labour market (partly by legislation

barring activist trade unionism and partly by regulating the foreign labour supply) and

the tripartite wage determination at the National Wages Council, Singapore ensured that

its unit labour cost remained internationally competitive.

5 State-led development strategy

This section outlines some basic features of state-led development strategy.

5.1 Fiscal policy

Given the poor state of infrastructure, human resources and other critical factors for

economic growth, and the lack of private investment in these areas (due to market

14

failure or inadequate markets), the government has to play a leading role. This means a

predominant role for fiscal policy both for the development and stabilization of

economic cycles. This is, indeed, the recommendation of a recent IMF sponsored study

of the Pacific Island economies.

In the Pacific, the discouraging effects on private investment of high-

cost, low-quality utilities are aggravated by poor infrastructure. The

region’s governments, together with donors, need to strengthen public

investment efforts and ensure that such programs focus on developing

physical and human capital that complement rather than substitute for

private sector investment (Fichera 2006: 53).

Obviously the question arises as to the financing of deficits and its implications for

inflation and external balance, as well as the sustainability of government debt. First, we

should note the ‘golden rule’—borrow to finance investment and balance

recurrent/routine expenditure. If borrowing is done to invest productively, then debt will

remain sustainable—economic growth will generate revenues to repair the budget

deficit. Second, the aim should be to maintain debt sustainability over the cycle. That is,

to have the political will to offset higher deficits incurred during downturns with higher

revenues during the upswings. This may also mean adjusting back the safety-net and

reducing the expenditure designed to jump-start the economy as well as expanding the

revenue base.

It is to be noted that a number of Caribbean and Pacific Island economies have fiscal

stabilization funds. Reserves are accumulated in these funds during commodity booms

to be used during the downswings. However, there are considerable doubts about the

robustness of the political system, and elites in Caribbean and Pacific Island economies

needed to prevent procycle bias of fiscal measures. Nonetheless, a number of

institutional measures can be suggested to ensure the viability of countercyclical fiscal

measures. For example, Perry (2003) believes that legislations regarding the

government’s fiscal behaviour during upswings and downswings of the economy can

potentially remove the pro-cycle bias of fiscal policy.

19

However, the fiscal rule faces

the dilemma between flexibility and credibility. Too rigid a rule to achieve credibility

may lead to high costs in forgone flexibility. The fiscal rule to support countercyclical

fiscal measures must also ensure long-term debt sustainability. Designing rules to

balance between flexibility, credibility and sustainability may not be an easy task.

Reviewing a number of countries that have some kind of fiscal rules, Perry finds the

rule recently adopted by Chile requiring structural balance or model structural surplus

most useful.

20

However, given the development needs of the small island economies, the fact remains

that the governments will have to borrow in the short to medium-terms. Due to poor

credit rating in the international capital markets and the lack of a well-developed

domestic capital market, the governments have two options for borrowing:

19

Singapore has a legislation barring the current government’s access to accumulated reserves to

prevent politically motivated expenditure.

20

Application of Chilean type fiscal rule requires improvement of fiscal accounting, reliable estimation

of potential output, and revenue elasticities. Countries would also have to develop ways to adjust for

the cyclical components in interest rates.

15

(i) borrowing from central banks and (ii) foreign aid. Foreign aid, indeed, has been a

significant source of government financing in both Caribbean and Pacific Island

economies.

Borrowing from central banks

Borrowing from central banks will increase money supply.

21

The endogeniety of money

supply will prevent interest rates from rising, and hence, there will be no possibility of a

crowding-out effect. On the contrary, government investment in infrastructure and

human resource development is likely to crowd-in private investment.

22

While

improved infrastructure reduces business costs, subsidized provisions of public health

and education can be regarded as social wage, which dampens wage demand. Both

factors enhance the investment climate.

23

Additionally, since the productive capacity of the economy is likely to expand with

public investment, the increase in money supply will not be as inflationary. In any case,

a moderate level of inflation is not found to be harmful for economic growth.

24

In the

absence of a well-developed taxation system, inflationary tax (or seigniorage) becomes

an important source of government revenue for financing development.

25

Foreign aid

It is a non-inflationary source of finance for the government. Foreign aid already plays a

significant role. Pacific Island economies are one of the highest aid recipients among the

developing world. There is a general perception, however, that the large aid flows failed

to spur rapid economic growth.

26

A recent comprehensive study of seven Pacific Island

economies, however, finds a statistically significant positive relationship between aid

and growth with diminishing returns (Pavlov and Sugden 2006).

27

This finding is

consistent with findings elsewhere and is not sensitive to either the policy environment

or institutions. One recent World Bank study (2002a) also reports a positive relationship

between foreign aid and economic growth in the Caribbean region. Thus, the findings

21

This option is available only to countries with their own currencies, controlled by a monetary

authority. The option is also limited for countries with a currency board that links domestic money

strictly to the availability of foreign currencies.

22

World Bank (1998: xii), notes that in Pacific Island economies, “Basic education, health care, and

physical infrastructure are the highest priorities to improve living standards for the widest group of

poor people, and to lay the foundations for sustained, broad-based income growth.”

23

This is in fact the experience of the successful East and Southeast Asian economies.

24

See Chowdhury (2006).

25

See Kalecki (1976).

26

See, for example, Feeny (2007). However, a negative correlation between aid flows and economic

growth could be just a statistical artefact. It may be due to the fact that in most cases, aid flows

respond to natural disasters and other negative supply shocks which retard growth. None of the studies

that report a negative aid-growth relationship conducted any counter-factual analysis. That is, what

would have happened in the absence of aid? If aid responds to negative supply shocks then the non-

availability of aid is likely to exacerbate the impact of negative supply shocks and there would be a

deeper drop in income.

27

The seven Pacific Island economies studied are Cook Islands, Fiji, Kiribati, Samoa, Solomon Islands,

Tonga and Vanuatu.

16

imply that much of the lessons learnt in other countries are largely applicable to the

Caribbean and Pacific Island economies.

The apparent lack of aid effectiveness or diminishing returns to aid can be traced to a

number of confounding factors. First is the uncertainty of disbursements and the

divergence between commitments and disbursements. Aid volatility can cause

significant problems for project implementation and government budget. Second, aid is

fraught with principal-agent problems. The recipient countries not only renege on

commitment to reforms, but also divert aid funds to undesirable uses, such as

government consumption or development projects chosen purely on political grounds.

Third, diminishing returns to aid could result from the lack of absorptive capacity. This

may arise from a number of reasons, such as inability to provide counter-fund,

deficiencies in planning and sequencing, as well as lack of administrative capacity.

Finally, large aid flows can cause real appreciation of local currencies to the detriment

of the tradable sector, known as Dutch disease syndrome.

28

The key element for addressing the above issues is the predictability of aid flows and

confidence in the donor-recipient relationship. The Caribbean and Pacific Island

economies experience high volatility of fiscal revenues due to their heavy reliance on

trade. Aid is needed to smooth out fluctuations in revenues and should not be another

source of shocks to the budget. Perhaps a ‘fiscal insurance scheme’ could be developed

for the respective regions with donor funds to address volatility in fiscal revenues.

29

That is, donors can contribute a certain portion of aid to a regional common pool to be

drawn by the country facing unforseen declines in fiscal revenues. The recipient

countries should also contribute to this regional common pool a certain portion of their

revenue windfalls.

30

A jointly managed regional common pool or the fiscal insurance

scheme as suggested above can play a positive role in improving donor-recipient

relations.

Donors can help overcome some of the absorptive capacity problems by not requiring

counter-fund and providing technical assistance in aid management and administration.

Other measures can also be considered to monitor aid administration. For example, aid

may be used in helping national governments to strengthen democratic institutions

designed for checks and balance on government expenditure.

Finally, the possibility of Dutch disease is remote, as these countries do not operate at

full employment, a vital assumption of the Dutch disease hypothesis. Moreover, the

Dutch disease syndrome can be avoided in a number of ways. First, if aid is used for

direct imports and/or technical assistance, then there is no need for real appreciation for

28

For evidence of Dutch disease syndrome in Pacific micro states, see Laplange, Treadgold and Baldry

(2001).

29

dos Reis (2004) highlights the usefulness of a fiscal insurance scheme for the countries of the

Caribbean Currency Union. Such a scheme can alleviate problems of policy coordination within a

currency union.

30

Some Pacific countries already have a fiscal stabilization fund. The regional stabilization fund can

supplement the national fund.

17

resource transfer to occur. Second, if aid is used for productivity enhancing investment,

then that offsets the impact of real exchange rate on competitiveness.

31

5.2 Monetary policy

Growth-oriented monetary policy has two features. First, as noted in the discussion

about fiscal policy, monetary policy has to be accommodative to governments’

investment needs. This is premised on the large body of empirical evidence that

moderate inflation does not harm economic growth, and may even be necessary.

Furthermore, an accommodative monetary policy is needed to ease the counter-fund

problem for the utilization of aid and hence enhance the absorption of aid.

32

Second, the monetary authorities should use low cost directed credits to support

labour-intensive SMEs. The subsidized special credit programmes, of course, distort the

credit market as well as run the risk of being infected with rent-seeking behaviour.

However, the costs of distortions and rent-seeking have to be weighed against the costs

of market failures in the credit market which result in discrimination against the SMEs

and the agriculture sector.

33

One may have concerns about the impact of low interest policies on savings and

financial sector development. To begin with, low real interest rates must not mean

negative real deposit interest rates which, in fact, have been the case in a number of

Caribbean and Pacific Island economies. Second, empirical evidence shows that in

low-income countries, financial development is mainly demand led. That is, it follows

growth. This is consistent with the observation that current income plays a more

dominant role in household savings decisions than the interest rate. Additionally, as the

experience of Singapore shows, rapid mobilization of domestic savings depends more

on non-market measures such as compulsory savings schemes and public sector

surpluses than on real interest rates. Finally, low interest rate policy has advantages for

both public debt sustainability and low inflation. It reduces interest payments on public

debt as well as the business cost on account of working capital. Both factors contribute

to low inflation.

5.3 Exchange rate and capital account policies

The Caribbean and Pacific Island economies have exchange rate systems ranging from

currency union to dollarized and floating regimes. As expected, the dollarized

economies have inflation rates close to the rates in the country of the currency they use,

31

See Chowdhury and McKinley (2007).

32

The traditional rationale for aid is to fill the savings-investment gap and the current account gap. The

savings-investment gap is generally related to government budget deficit. Aid funds are converted into

domestic currency to be spent by the government which causes inflationary pressure leading to real

appreciation. The real appreciation, in turn, causes higher imports to be financed by foreign currencies

made available through aid in the first place. This is the normal channel through which aid gets spent

and absorbed. Conservative fiscal and monetary policies, thus, only lead to accumulation of foreign

reserves and defeat the purpose of aid. See Chowdhury and McKinley (2007).

33

See Chowdhury (2006) for an illustration of various monetary policy instruments for achieving both

employment and moderate inflation targets.

18

and the countries with an independently floating system have higher inflation rates. The

economies with a pegged exchange rate system have mixed experiences with inflation.

As opposed to IMF’s suggestion for freer and more flexible currency regimes, recently

some observers argued for a dollarized regime for the Pacific region, and the use of the

Australian dollar in the Pacific economies.

34

The argument is based on the insufficient

depth of domestic financial and foreign exchange markets to support the liquidity

necessary to maintain a freely floating exchange rate, and the lack of skilled personnel

to run a central bank. The adoption of a strong foreign currency is also likely to impose

fiscal discipline in economies where maintaining central bank independence is difficult.

Some have also examined the possibility of forming a currency union like the East

Caribbean Monetary Union.

35

While dollarization improves macroeconomic stability, the main objection to it may

arise from the vastly different types of shocks between the Pacific Island economies and

the country of strong currency (Australia, New Zealand and the US). Thus, responses to

these shocks require some macroeconomic policy independence which will be lost if

dollarized. Very low inflation rates of the strong currency country may be too

constraining for these economies, which are prone to supply shocks and need to undergo

structural change. Furthermore, dollarization will deprive them of seigniorage, and

hence an important source of revenue for countries with a poor domestic revenue base.

The currency unions are also not without problems, especially when there is a lack of

significant convergence of macroeconomic indicators. At the same time, when their

trade structure and partners are very similar, they are likely to suffer from the same

terms-of-trade shocks almost simultaneously. This can place enormous pressure on the

fiscal balance and monetary situation of all member countries, trying to adjust to the

shock.

Considering the pros and cons of various exchange rate regimes, it seems reasonable

that the small island economies should follow an adjustable peg exchange rate system.

As mentioned earlier, Singapore has been quite successful in using an adjustable peg

exchange rate system to contain inflation.

36

However, an economy (or economic union) cannot have macroeconomic policy

independence and open capital account under a pegged exchange rate system. This

means there should be some restrictions on capital mobility. Neither the Caribbean nor

the Pacific region receives much short-term private capital. Their main source of outside

capital is foreign aid and workers’ remittance, which are not sensitive to interest rates.

Their main problem is capital outflow, and it makes sense to have some controls on

34

de Brouwer (2002); Duncan (2002). Jayaraman (2005) does not find much support for using

Australian dollar. Based on trade flow statistics, he argued that there is stronger case of adopting an

Asian currency. Bowman (2006) concludes: ‘dollarization to the US dollar, the de-facto standard in

Asia, or a move to a common currency may be preferable alternatives to dollarizing to the Australian

dollar’.

35

Jayaraman, Ward and Xu (2005).

36

See Drake (1983) for a comprehensive discussion of exchange rate choices for small open economies.

Drake suggests an intermediate regime between an absolutely fixed exchange rate regime with no

monetary discretion and a fully flexible exchange rate regime with monetary discretion.

19

capital flights. Restrictions on short-term capital outflows do not necessarily create any

disincentives for long-term foreign direct investment.

5 Concluding remarks

This paper has reviewed the macroeconomic performance of Caribbean and Pacific

Island economies. Given the high volatility of their output growth and its adverse

impacts on long-term growth as well as on the poor, the paper argued for the output

stabilization role of macroeconomic policies. Drawing on the experience of Singapore,

the paper also argued that contrary to the conventional wisdom, macroeconomic policies

can play both stabilization and directly growth-promoting roles in highly open small

economies. However, it requires some appropriate institutional frameworks to regulate

the labour market, mobilization of savings, movements of short-term capital (capital

flights), and the government’s fiscal behaviour. Given high aid-dependency, there also

needs to be improvement in aid delivery and aid management.

However, no one country is identical to another, and there are considerable differences

among groups of countries. Thus, small island states need to be innovative in designing

their own institutions based on their own history and context. Furthermore, given their

size, remoteness and other constraints, it seems they would be better off by pooling

regional capacity and resources. This would entail opening up their own markets to

inflows of goods, services, capital and labour from the region, something akin to a

currency union.

References

Abbott, D., and S. Pollard (2004). Hardship and Poverty in the Pacific. Manila: Asian

Development Bank.

Armstrong, H., R. de Kervenoael, X. Li, and R. Read (1998). ‘A Comparison of the

Economic Performance of Different Microstates and between Microstates and Larger

Countries’. World Development, 26 (4): 639-56.

Atkins, J. P., S. A. Mazzi, and C. D. Easter (2000). ‘Commonwealth vulnerability Index

for Developing Countries: The Position of Small States’. Economic Paper 40.

London. Commonwealth Secretariat.

Bourne, C. (2005). ‘Poverty and its Alleviation in the Caribbean’. Lecture presented at

the Alfred O. Heath Distinguished Speakers’ Forum, 14 March. St. Thomas:

University of the Virgin Islands.

Bowman, C. (2006). ‘The Governor or the Sheriff? Pacific Island Nations and

Dollarization’. Canberra: Asia Pacific School of Economics & Government, ANU.

Mimeo.

Briguglio, L. (1995). ‘Small Island Developing States and Their Economic

Vulnerability’. World Development, 23 (9): 1615-32.

Caram, A. (1989). ‘Guidelines for Monetary Policy in Small Developing Countries’.

In

J. Kamanarides, L. Briguglio and H. Hoogendonk (eds), The Economic Development

20

of Small Countries: Problems, Strategies and Policies. Delft: Eburon (in conjunction

with the Foundation for International Studies, University of Malta and the Faculty of

Economics, University of Amsterdam), 39-56.

Chowdhury, A. (2006). ‘The “Stabilization Trap” and Poverty Reduction—What Can

Monetary Policy Do?’. Indian Development Review, 4 (2): 407-32.

Chowdhury, A., and T. McKinley (2007). ‘Gearing Macroeconomic Policies to Manage

Large Inflows of ODA: The Implications for HIV/AIDS Programmes’. WIDER

Research Paper 2007/34. Helsinki: UNU-WIDER.

Commonwealth Secretariat (2000). ‘Small States: Meeting Challenges in the Global

Economy’. Paper prepared for the Commonwealth Secretariat/World Bank Joint

Task Force on Small States. Washington DC: Commonwealth Secretariat-World

Bank.

Corden, M. (1984). ‘Macroeconomic Targets and Instruments for a Small Open

Economy’. Singapore Economic Review, 29 (2): 27-37.

de Brouwer, G. (2002). ‘Should Pacific Island Nations Adopt the Australian Dollar?’.

Pacific Economic Bulletin, 15 (2): 161-69.

de Ferranti, D., G. Perry, I. Gill, and L. Serven (2000). Securing Our Future in a Global

Economy, Washington DC: World Bank.

dos Reis, L. (2004). ‘A Fiscal Insurance Scheme for the Eastern Caribbean Currency

Union’. Paper presented at the XVIII G24 Technical Group Meeting, 8-9 March.

Drake, P. (1983). ‘Monetary and Exchange Rate Management in Tiny Open

Underdeveloped Economies’. Savings and Development, 7 (1): 4-19.

Duncan, R. (2002). Dollarizing the Solomon Island Economy’. Pacific Economic

Bulletin, 15 (2): 143-46.

Easterly, W., and A. Kraay (2000). Small States, Small Problems? Income, Growth, and

Volatility in Small States’. World Development, 28 (11): 2013-27.

ECLAC (2006). Economic Survey of the Caribbean 2005-2006. Santiago: ECLAC.

ESCAP (2006). Economic and Social Survey of Asia and the Pacific, 2006. New York

and Bangkok: UN-Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific, 66-7.

Eslava, M. (2006). ‘The Political Economy of Fiscal Policy: Survey’. Inter-American

Development Bank Working Paper 583. Washington, DC: IADB.

Feeny, S. (2007). ‘Growth Impacts of Foreign Aid to Melanesia’. Journal of the Asia

Pacific Economy, 12 (1): 34-60.

Fichera, V. (2006). ‘The Pacific Islands and the Eastern Caribbean Currency Union:

A Comparative Review’. In C. Browne (ed.), Pacific Island Economies. Washington

DC: IMF.

Gavin, M., R. Hausmann, R. Perotti, and E. Talvi (1996). ‘Managing Fiscal Policy in

Latin America and the Caribbean: Volatility, Procyclicality and Limited

Credit-worthiness’. RES Working Paper 326. Washington, DC: Inter-American

Development Bank.

21

Glewwe, P., and G. Hall (1998). ‘Are Some Groups More Vulnerable to

Macroeconomic Shocks than Others? Hypothesis Tests Based on Panel Data from

Peru’. Journal of Development Economics, 56 (1): 181-206.

Huff, W. (1995). ‘What Is the Singapore Model of Economic Development?’.

Cambridge Journal of Economics, 19 (6): 735-59.

Jayaraman, T. (2005). ‘Dollarization of the Pacific Island Countries: Results of a

Preliminary Study’. Working Paper 2005/1. Suva: Department of Economics,

University of South Pacific.

Jayaraman, T., B. Ward, and Z. Xu (2005). ‘Are the Pacific Islands Ready for a

Currency Union?: An Empirical Study of Degree of Economic Convergence’.

Working Paper 2005/2. Suva: Department. of Economics, University of South

Pacific.

Kalecki, M. (1976). Essays on Development Economics. Brighton: Harvester Press.

Khatkhate, D., and B. Short (1980). ‘Monetary and Central Banking Problems of Mini

States’. World Development, 8 (12): 1017-25.

Kuznets, S. (1960). ‘Economic Growth of Small Nations’. In E. A. G. Robinson (ed.),

The Economic Consequences of the Size of Nations. London: Macmillan.

Laplange, P., M. Treadgold, and J. Baldry (2001). ‘A Model of Aid Impact in Some

South Pacific Microstates’. World Development, 29 (2): 365-83.

Lodewijks, J. (1988). ‘Employment and Wages Policy in Papua New Guinea’. Journal

of Industrial Relations, 30 (3): 381-411.

Milner, C., and T. Westaway (1993). ‘Country Size and the Medium-term Growth

Process: Some Cross-country Evidence’. World Development, 21 (2): 203-11.

Nadal-De Simone, F. (2000). ‘Monetary and Fiscal Policy Interaction in a Small Open

Economy: The Case of Singapore’. Asian Economic Journal, 14 (2): 211-31.

Oxfam (2007). ‘Poverty in the Pacific’. Available at: www.oxfam.org.nz.

Pavlov, V., and C. Sugden (2006). ‘Aid and Growth in the Pacific Islands’. Asian-

Pacific Economic Literature, 20 (2): 38-55.

Perry, G. (2003). ‘Can Fiscal Rules Help Reduce Macroeconomic Volatility in Latin

America and the Caribbean Region?’. WB Policy Research Working Paper 3080.

Washington, DC: World Bank.

Scitovsky, T. (1958). Economic Theory and Western European Integration. London:

Allen & Unwin.

Siwatibau, S. (1993). ‘Macroeconomic Management in the Small Open Economies of

the Pacific’. In R. Cole and S. Tambunlertchai (eds), The Future of the Asia-Pacific

Economies – Pacific Island Economies at the CrossRoads? Canberra: Pacific

Development Centre and the National Centre for Development Studies, ANU.

Srinivasan, T. N. (1986). ‘The Costs and Benefits of Being a Small Remote Island

Land-locked or Mini-state Economy’. World Bank Research Observer

, 1 (2): 205-18.

Streeten, P. (1993). ‘The Special Problems of Small Countries’. World Development, 21

(2): 197-202.

22

Toh, M.-h. (2005). ‘Singapore’. Pacific Economic Outlook, 2005-2006. Hong Kong:

APEC Centre.

Treadgold, M. (1992). ‘Openness and the Scope for Macroeconomic Policy in Micro

States’. Cyprus Journal of Economics, 5 (1): 15-24.

UNDP (various years). Human Development Report. New York: UNDP.

Williamson, J. (2004). ‘The Washington Consensus as Policy Prescription for

Development’. WB Lecture Series Practitioners of Development. 13 January.

Washington, DC: World Bank.

World Bank (1998). Enhancing the Role of Government in the Pacific Island

Economies. Washington, DC: World Bank.

World Bank (2000). World Development Report 2000/2001: Attacking Poverty.

Washington, DC: World Bank

World Bank (2002a) ‘Development Assistance and Economic Development in the

Caribbean Region: Is there a Correlation?’. Report No. 24164-LAC. Washington,

DC: Caribbean Group for Cooperation in Economic Development, World Bank,.

World Bank (2002b). ‘Caribbean Economic Overview, 2000: Macroeconomic

Volatility, Household Vulnerability, and Institutional and Policy Responses’.

Concept Paper. Washington, DC: Caribbean Group for Cooperation in Economic

Development, World Bank.

World Bank (2006). World Economic and Social Survey, 2006: Diverging Growth and

Development. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Worrell, D. (1987). Small Island Economies: Structure and Performance in the English-

Speaking Caribbean since 1970. New York: Praeger.