Implementation Handbook for

UN sanctions on North Korea

Compliance and Capacity Skills International in partnership with CRDF Global

Implementation Handbook for

UN sanctions on North Korea

By

Compliance and Capacity Skills International

in partnership with

CRDF Global

March 2019

Washington, DC, US

This publication is based on work supported by CRDF Global.

Any opinions, ndings and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those

of the authors and do not necessarily reect the views of CRDF Global

Introduction

The handbook on the implementation of UN sanctions on North Korea is a revised version of the original

volume titled United Nations Non-Proliferation Regimes on Iran and North Korea published by Compliance and

Capacity Skills International in November 2015.

The text of the present handbook was revised to reflect changes that have taken place in United Nations

non-proliferation sanctions. The changes relate to substantial expansions of the 1718 sanctions regime on

North Korea and termination of the Iran sanctions regime under Security Council resolution 1737 with the

Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action that the UN Security Council endorsed with resolution 2231 (2015).

The handbook also underwent major revisions in order to answer the unique sanctions implementation

challenges that many states and companies face. Some may have long-standing diplomatic or economic

relationships with the Democratic People’s Republic of North Korea (DPRK). Others are experiencing

diplomatic disruptions over the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, related ballistic missile

development, or North Korea’s prolific exports of conventional arms.

The handbook is structured into seven chapters that explore the DPRK’s position in the world and

its political and trading roles when it partners with developing and other countries. The book further

describes reported activities that contravene UN sanctions and introduces the principal actors behind these

activities. Typically, they are supported by parastatal conglomerates whose activities on the African and

Asian continents are subject to intense scrutiny by UN sanctions specialists.

The handbook also describes the growing UN sanctions measures currently applied on North Korea and

how these measures are embedded within the broader context of other UN sanctions.

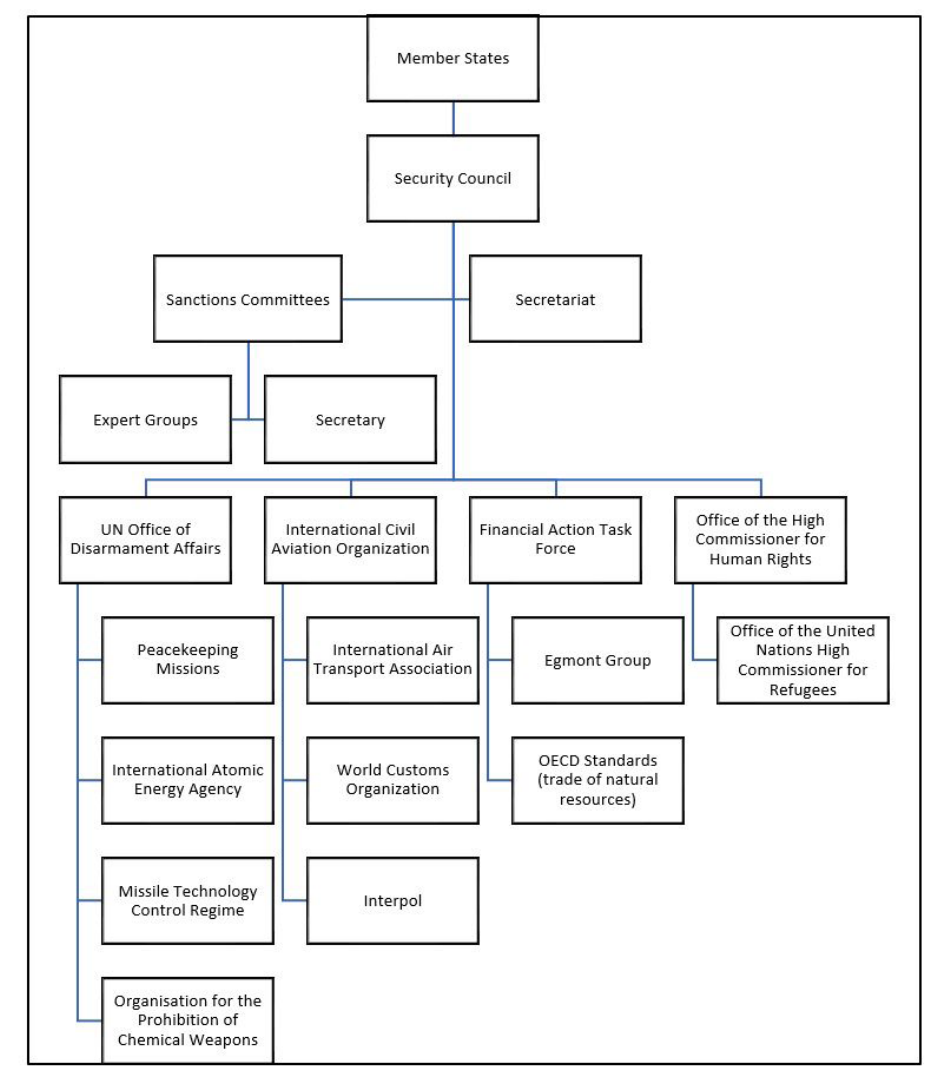

Furthermore, the handbook explains the UN sanctions architecture with its various actors, giving a

detailed account of UN sanctions measures along with specific descriptions of implementation obligations

that state governments and corporate management must meet.

Finally, the book offers in the last two chapters a blueprint for government implementors or corporate

compliance officers who wish to establish an organization-wide sanctions implementation and compliance

system.

The texts were authored by Enrico Carisch and edited by Loraine Rickard-Martin, with the research

assistance of Ola al-Tamimi, Anastasia Borosova, Won Jang, Jake Sprang, Alfredo Villavicencio and

Samantha Taylor.

Instead of an index, this book offers a very detailed table of contents in order to facilitate quick searches for

content that hopefully answer readers’ specific information needs.

i.

Introduction ...................................................................................i.

I.The Ubiquitous Hermit Kingdom .......................................................1

North Korea’s presence in the world ............................................................................1

Juche in Asia ....................................................................................................................3

Japan .............................................................................................................................3

Indonesia ........................................................................................................................3

Vietnam .......................................................................................................................... 4

Singapore ........................................................................................................................4

Other Asian nations ............................................................................................................ 5

Yemen ............................................................................................................................ 5

Africa ............................................................................................................................6

Latin America Region .........................................................................................................8

Risks of global trade and DPRK sanctions violations ........................................................8

II.North Korea’s Military Diplomacy and UN Sanctions ............................ 10

Education and training ......................................................................................... 10

Supply of military goods and services ......................................................................... 11

The rapid expansion of sanctions measures .............................................................................. 11

UN expert reports ........................................................................................................... 13

Commodity trade with North Korea ..................................................................................... 17

Sanctions implementation reporting ...................................................................................... 19

III.North Korean Conglomerates ........................................................ 21

Background ....................................................................................................... 21

From licit to illicit operators ............................................................................................... 21

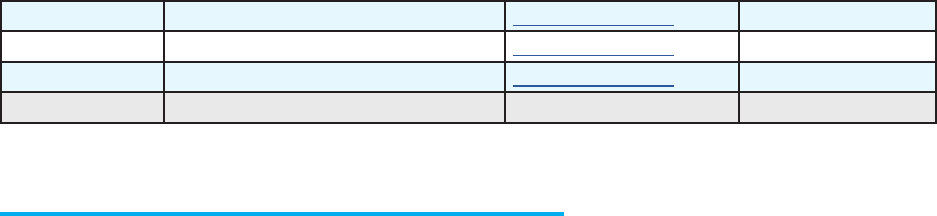

Korea Mining Development Trading Corporation ........................................................... 21

The network .................................................................................................................. 21

Global partners ............................................................................................................... 21

Defense industries ........................................................................................................... 22

KOMID’s sanctions violation strategies .................................................................................. 22

Designation for UN sanctions measures.................................................................................. 23

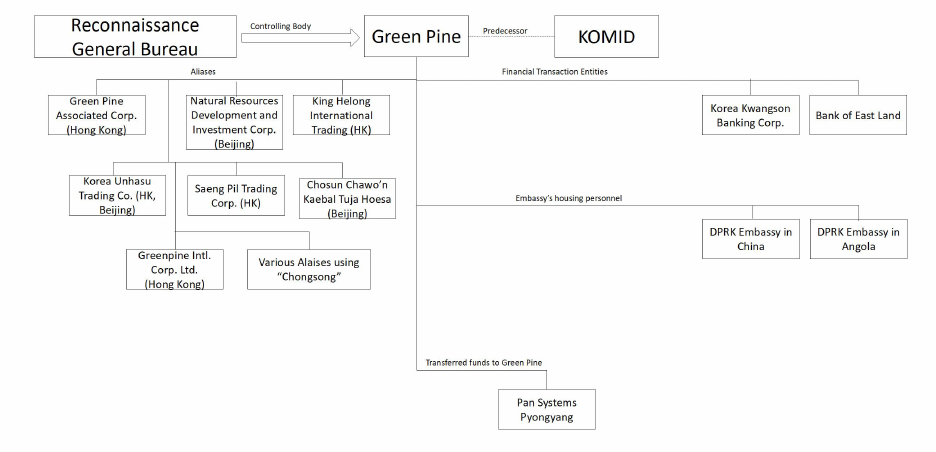

Green Pine Associated Corporation ............................................................................ 25

The network .................................................................................................................. 25

Defense industries ........................................................................................................... 25

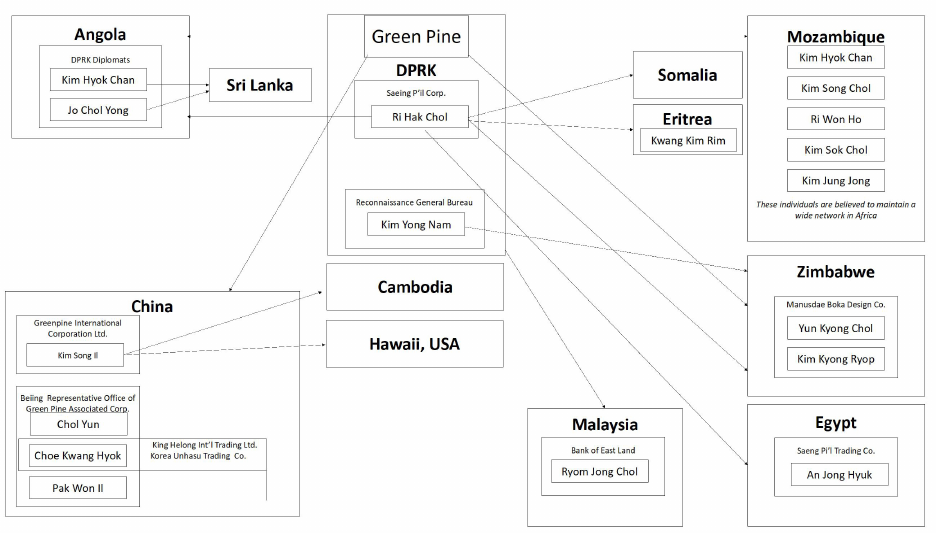

Identified Green Pine agents ............................................................................................... 27

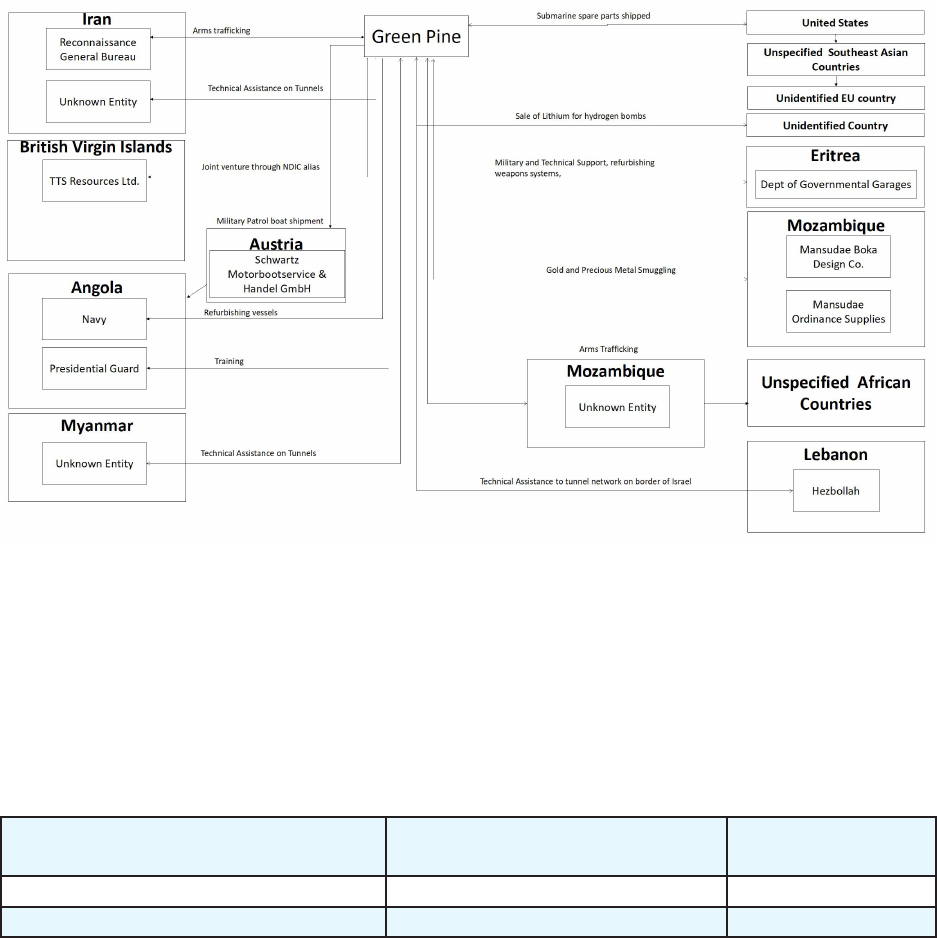

Observed activities and sanctions violations ............................................................................. 27

Protecting against compliance failures ....................................................................... 28

Vigilance ....................................................................................................................... 28

Actors versus activities ...................................................................................................... 28

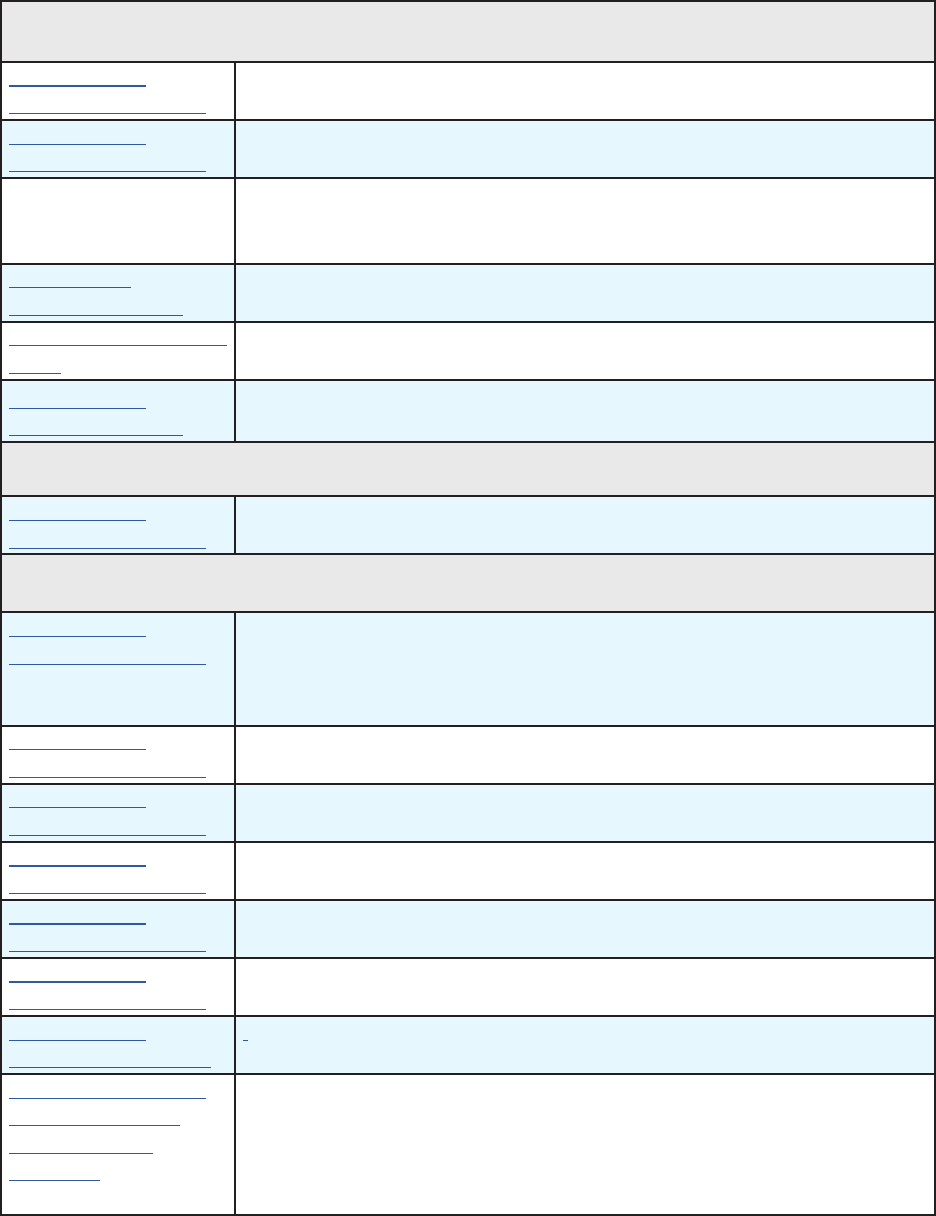

Table of Contents

ii.

IV.The UN Sanctions Environment ...................................................... 28

Overview ........................................................................................................... 28

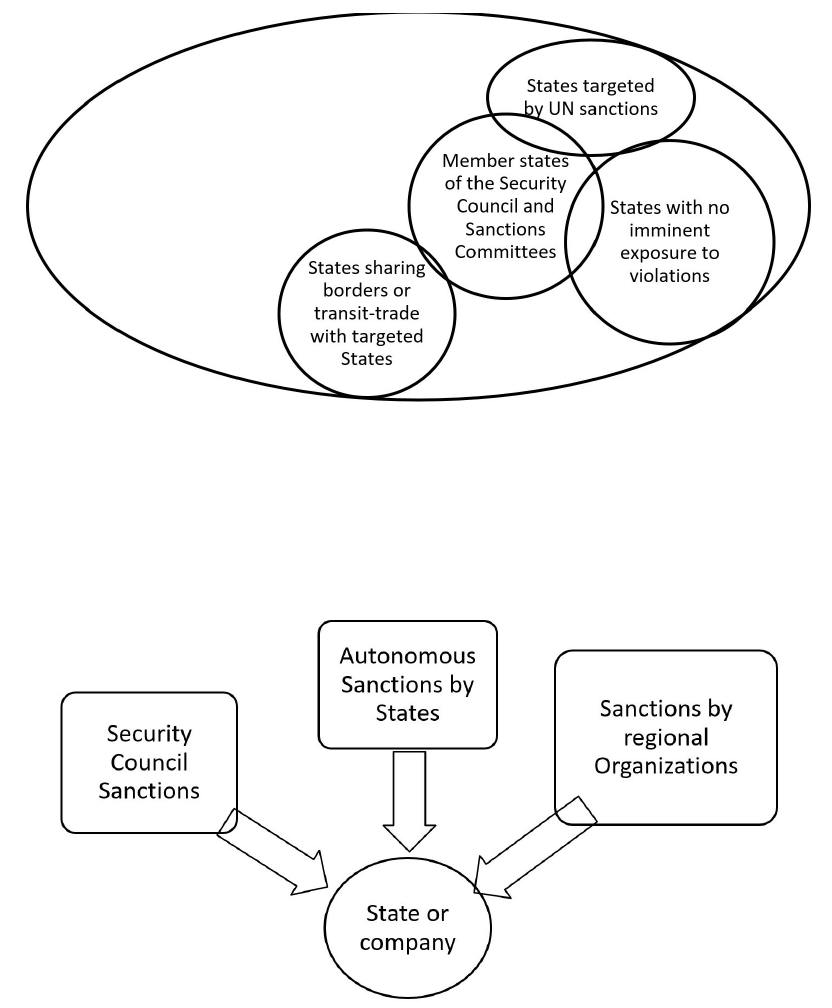

Understanding UN sanctions actors ...................................................................................... 28

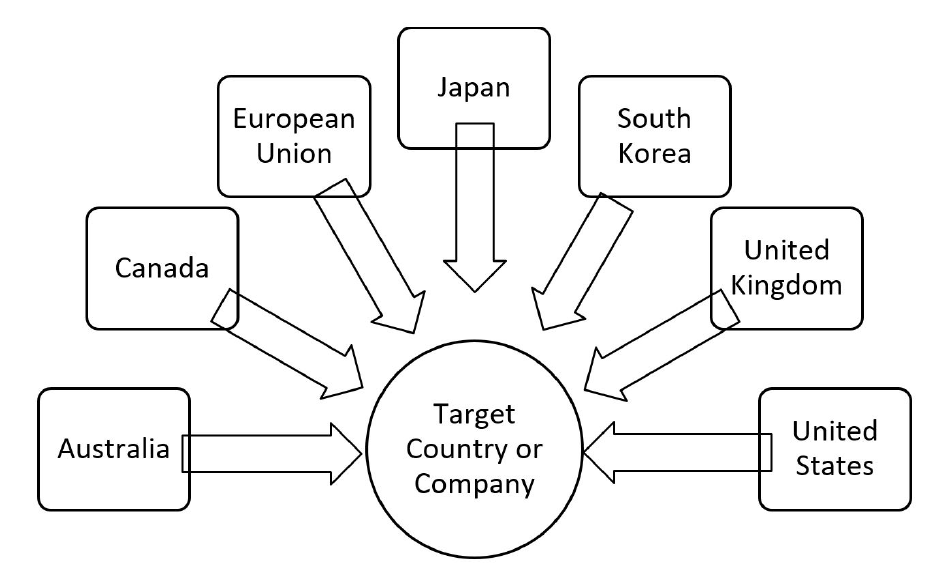

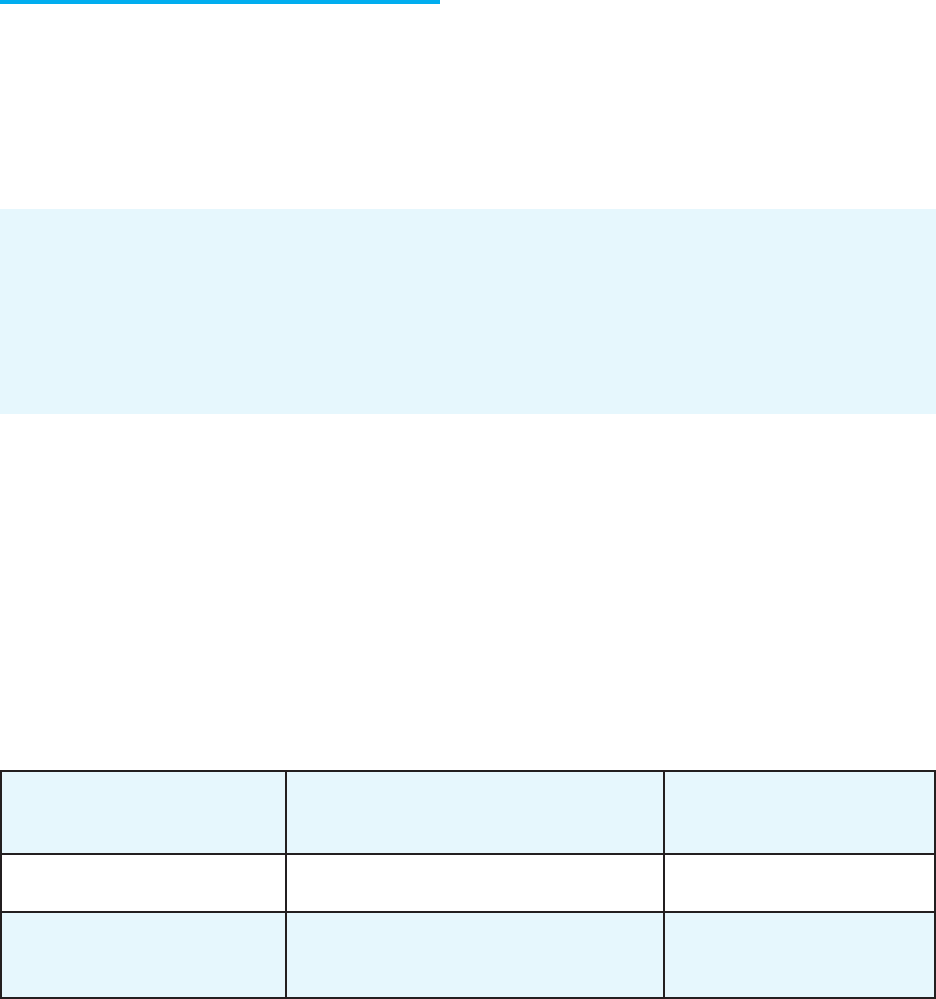

Exposure to sanctions issued by the UN and others ................................................................... 30

Multiple sanctions actors ................................................................................................... 30

Legal obligations ............................................................................................................. 31

Consequences of UN sanctions violations ............................................................................... 31

Prerequisite for national constitutional, legal and regulatory instruments ......................................... 31

Authorization procedures mandated by the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action under

resolution 2231 (2015) ........................................................................................ 32

The JCPOA agreement ..................................................................................................... 32

Conventional arms transfers* .............................................................................................. 32

Nuclear-related transfers and activities *** ............................................................................. 32

Ballistic missile-related transfers and activities ** ...................................................................... 33

Travel ban* .................................................................................................................... 33

V. UN Sanctions Measures ................................................................ 34

Overview ........................................................................................................... 34

Sanctions regimes currently in force...................................................................................... 34

Sanctions measures ............................................................................................... 34

Types of sanctions measures ................................................................................................ 34

Related international legal instruments ..................................................................... 35

Sanctions-supporting international instruments and guidance ....................................................... 35

Embargoes and Bans ............................................................................................. 35

General observations ........................................................................................................ 35

Definitional issues ............................................................................................................ 36

UN embargo against conventional arms ..................................................................... 36

Two-way arms embargo .................................................................................................... 36

What is covered by the embargo? ........................................................................................ 36

DPRK arms embargo ....................................................................................................... 36

Dual use items ................................................................................................................ 36

DPRK and dual use issues .................................................................................................. 37

Exemptions to conventional arms embargoes ........................................................................... 37

Embargo on conventional arms ............................................................................................ 38

Embargo against weapons of mass destruction .......................................................................... 38

DPRK and two-way embargo .............................................................................................. 38

What falls under the embargo? ............................................................................................ 38

Dual use items ................................................................................................................ 39

Catch-All Provisions ......................................................................................................... 39

Commodity embargoes .......................................................................................... 40

General observations ........................................................................................................ 40

iii.

What falls under the embargo? ............................................................................................ 40

What are the implementation obligations regarding UN commodity restrictions for states or companies? .. 41

Luxury goods embargo ........................................................................................... 41

General observations ........................................................................................................ 41

What falls under the embargo? ............................................................................................ 41

What are implementation obligations concerning UN luxury sanctions for states or companies .............. 42

UN sanctions on human trafcking and employment ..................................................... 42

General observations ........................................................................................................ 42

What is covered by the ban? ................................................................................................ 42

What are the implementation obligations with sanctions against human trafficking and employment for

states? .......................................................................................................................... 43

Infrastructure restrictions ....................................................................................... 43

General observations ........................................................................................................ 43

Assets freeze .................................................................................................................. 43

What is covered by an assets freeze? ...................................................................................... 43

What are implementation obligations of states in regards to sanctions against human trafficking ............. 45

Denial of nancial services ..................................................................................... 45

General observations ........................................................................................................ 45

What is covered by the denial of financial services? .................................................................... 45

Implementation obligations of states in regards to sanctions against nancial services .............. 46

Travel ban ......................................................................................................... 46

General Overview ........................................................................................................... 46

What is covered with a UN travel ban? ................................................................................... 46

Implementation obligations of states in regards to the UN travel ban .............................................. 47

Restrictions on maritime, aviation, and land transportation ............................................. 47

General overview ............................................................................................................ 47

Specific restrictions under DPRK sanctions ............................................................................. 47

Blocking of diplomatic, sports, or cultural activities ....................................................... 49

Restricting diplomatic privileges .......................................................................................... 49

What is covered under the restrictions on diplomatic interactions? ................................................. 49

Implementation obligations of states in regards to the UN diplomatic restrictions ............................... 49

Restricting sports activities ..................................................................................... 50

General Overview ........................................................................................................... 50

Restricting educational services ................................................................................ 50

General Overview ........................................................................................................... 50

What is covered by UN restrictions against educational services? ................................................... 50

What are the implementation obligations of states in regards to the UN sanctions against educational

services? ....................................................................................................................... 50

Restricting trade in cultural goods ............................................................................ 51

General Overview ........................................................................................................... 51

iv.

What is covered by UN restrictions against the trade in cultural goods? ........................................... 51

What are implementation obligations of states in regards to the UN’s restrictions on cultural goods? ....... 51

Supporting implementation guidance by the Security Council ........................................... 51

General Overview ........................................................................................................... 51

Implementation Assistance Notices ....................................................................................... 52

VI.Whole of Government Sanctions Implementation Mechanism ................. 53

Overview ........................................................................................................... 53

Purpose ........................................................................................................................ 53

Work-Flow ......................................................................................................... 54

General ........................................................................................................................ 54

Information ....................................................................................................... 54

Sanctions lists ................................................................................................................. 55

UN sanctions websites ...................................................................................................... 55

Sanctions measures .......................................................................................................... 55

Exemptions ................................................................................................................... 55

Informing the private sector ............................................................................................... 55

Due diligence expectations ................................................................................................. 56

Commercial Screening Tools ............................................................................................... 56

Implementation ................................................................................................... 56

General ........................................................................................................................ 56

Specific obligations .......................................................................................................... 56

Enforcement ....................................................................................................... 58

General ........................................................................................................................ 58

Banks and intermediaries of the financial industry ..................................................................... 58

Activity-based compliance.................................................................................................. 59

Suspicious transaction reports (STR) and sanctions .................................................................... 59

Indicators of likely sanctions violations ...................................................................... 59

Guidance from reliable sanctions actors ................................................................................. 59

Categories of indicators ..................................................................................................... 59

Atypical trade practices ..................................................................................................... 59

Identity and behavior of participants ..................................................................................... 60

Transport characteristics ................................................................................................... 60

Additional sector-specific indicators ...................................................................................... 60

Trade and export licensing authorities ................................................................................... 61

Customs and border control authorities ................................................................................. 61

Oversight authorities for financial services and financial intermediaries ........................................... 62

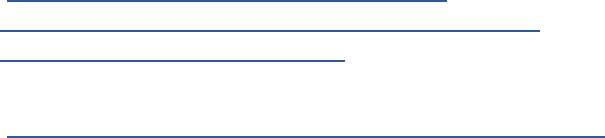

Typologies of sanctions violations ............................................................................. 63

Reporting and notication obligations ....................................................................... 67

Overview ...................................................................................................................... 67

v.

Exemption requests ............................................................................................... 71

No harmonized approach ................................................................................................... 71

Required information for exemption requests on grounds of humanitarian need, to obtain medical care,

or to attend to religious practices ......................................................................................... 71

An exemption from a travel ban for any other reasons ................................................................ 72

Requests for exemption to the assets freeze measures that facilitate payments of basic living expenses ...... 73

VII.Whole of Enterprise Sanctions Compliance Mechanism........................ 74

Unique challenges faced by companies ....................................................................... 74

Multiple sanctions issuers .................................................................................................. 74

Costs and Rewards ........................................................................................................... 74

Structure and participants .................................................................................................. 74

Work-Flow .................................................................................................................... 75

Information ....................................................................................................... 75

Awareness of sanctions lists ................................................................................................ 75

Understanding sanctions measures ........................................................................................ 76

Exemptions ................................................................................................................... 76

Due diligence obligations ................................................................................................... 76

Commercial screening tools ............................................................................................... 76

Compliance ........................................................................................................ 77

Implementation advisories ................................................................................................. 77

Specific Obligations .......................................................................................................... 77

Industry specic compliance guidance ........................................................................ 79

Manufacturers or other corporate actors involved with trade of military material or dual use item .......... 79

Transportation sector ....................................................................................................... 80

Transportation sector -- consignor and recipients of cargo shipments .............................................. 80

Compliance officers of the financial industry – bankers and account management ............................... 81

Compliance officers of the financial industry – intermediary financial services, including investment or

insurance services, issuance and brokering of credit instruments, equity and debt securities, and

facilitators of barter transactions .......................................................................................... 81

Typologies of sanctions violations ............................................................................. 82

vi.

1

I. The Ubiquitous Hermit Kingdom

Called the Hermit Kingdom since the 19th century, the modern Democratic People’s Republic of Korea is far

from a rigidly sealed country. Under three generations of the Kim family’s leadership, North Korea maintains

sequestration against unwelcome intruders but is open to friends and business partners. The DPRK has built

relationships around the world and advanced its strategic interests in diplomacy, in particular with its overseas

military diplomacy.

The country’s progress became an international menace when the DPRK overcame considerable technological

barriers to build an arsenal of nuclear weapons and ballistic missiles based on a less than mediocre economy

somewhere between that of Senegal and Mali. With slightly over USD 16 billion, North Korea’s gross domestic

product is about 20 times less than the economy of the next poorest nuclearized state, Pakistan, followed by

Israel (USD 350 billion), Russia (USD 1,580 billion), France (USD 2,580 billion), India (USD 2,600 billion),

the United Kingdom (USD 2,620 billion), China (USD 12,240 billion), and the US (USD 19,390 billion). An

inescapable consequence of the Kim family’s voracious appetite for military prowess is untold humanitarian

deprivation for many of the DPRK’s 25 million citizens.

The justification for UN sanctions against North Korea’s proliferation is based on a simple fact: withdrawal

from the Nonproliferation Treaty and persistent noncompliance with the international community’s rules

against the development and use of nuclear weapons marks the DPRK as a threat to international peace and

security.

In October 2006, the Security Council invoked measures provided for under Chapter VII of the UN Charter,

specifically Article 41 which authorizes the application of sanctions. The objective of sanctions resolution 1718

is the complete, verifiable, and irreversible dismantlement of North Korea’s nuclear arms program.

Ongoing bilateral negotiations to settle the decades-long hostilities between North and South Korea and the

United States will have no impact on UN sanctions, except in the case where any of these states succeeds in

convincing the Security Council to revoke the sanctions. Until that time, United Nations sanctions remain the

appropriate, non-violent tool for coercing the DPRK’s leadership into giving up its proliferation of weapons of

mass destruction.

The obligation to implement all sanctions measures remains in force as a matter of binding international law.

All states are required to understand and implement sanctions resolution 1718 adopted in October 2006, and

its successor resolutions, 1874 (2009), 2087 and 2094 (2013), 2270 and 2321 (2016), 2371 and 2375 (2017),

and finally resolution 2397 (2017).

The accumulated sanctions measures contained in these resolutions represent the most complex obligations

that UN member states must observe and implement. There is no doubt that these complexities stretch many

state’s implementation capacities, including in terms of providing guidance to or supervision of compliance by

their private sector. Political, cultural and strategic interests shared by many states with North Korea must be

considered to make UN sanctions implementation more effective.

North Korea’s presence in the world

Kim Il Sung, his son Kim Jon Il, and grandson Kim Jon Un, have fashioned from the very earliest days of the

DPRK’s existence a unique ideological identity that still resonates with Koreans and many others around the

world. First and foremost, Juche (pronounced joo-chey), speaks to Koreans’ sense of history and national

purpose. But it also serves as an overarching national theme and global propaganda tool with considerable

messaging power.

2

According to the DPRK’s official website

1

, Juche means “in a nutshell, that the masters of the revolution

and construction are the masses of the people and that they are also the motive force of the revolution and

construction”.

But “Juche” has also long appealed to intellectuals and politicians of formerly colonized countries. Their

shared experiences with the DPRK include foreign occupation, exploitation and sometimes enslavement of

their civilians, theft of natural resources and other national deprivation, and the struggle for liberation, self-

determination, and economic security. That Juche might be one of the few alternative avenues for nations that

wish to be independent of East-West dogmas is dramatically manifested by North Korea’s survival of the almost

70-year Cold War with South Korea and the United States.

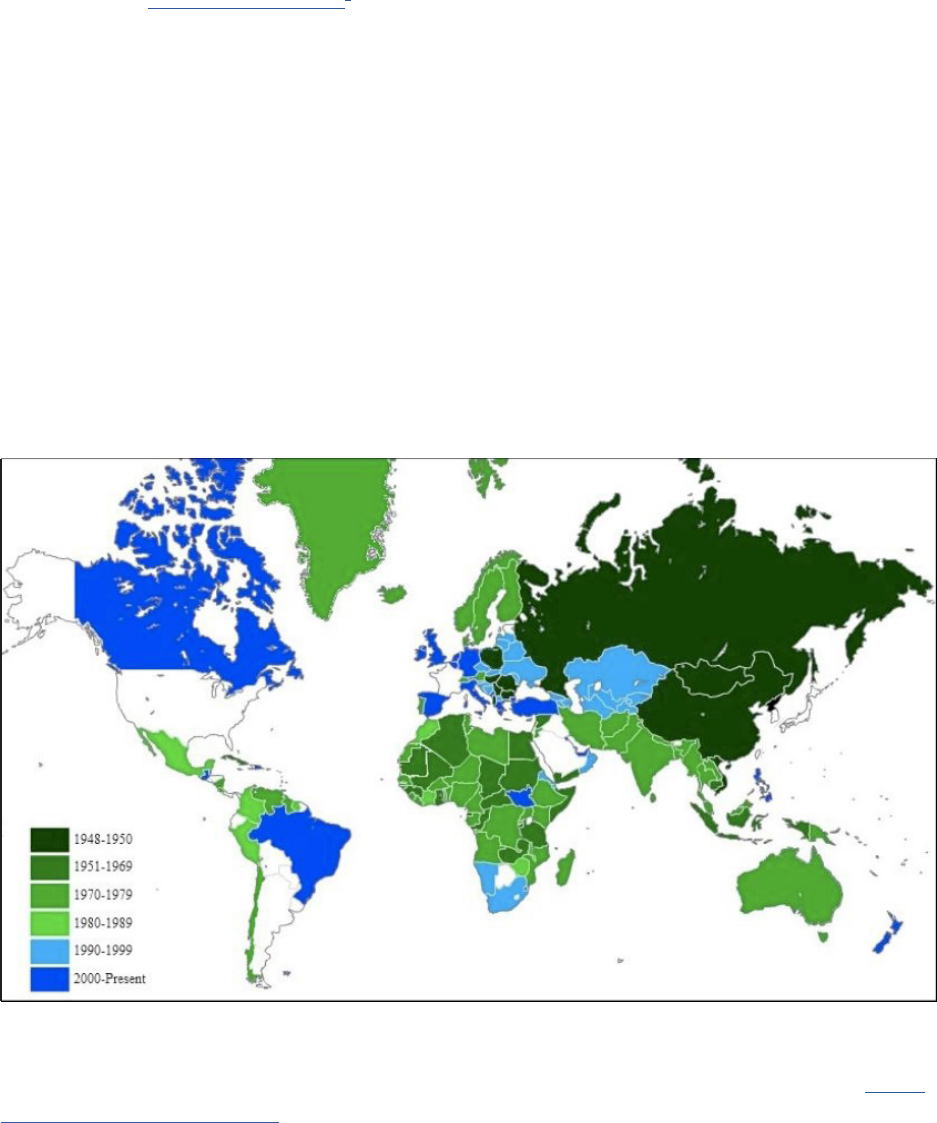

The global messaging power that Juche has generated is further validated by the survival of three generations

of the Kim regime despite decades of autonomous sanctions, and ever-increasing UN sanctions. The DPRK has

managed to steadily expand the span of its diplomatic relationships, as this map illustrates (Illustration 1, by

the National Committee on North Korea). A hundred and sixty-four countries have formally recognized North

Korea; albeit, for some countries, their diplomatic relations with the DPRK have fallen dormant in recent years.

An additional network that appears to be semi-official is the Korean Friendship Association (KFA) that claims to

be represented in 120 countries, including in the US and many European states. It operates the website ht t p://

www.korea-dpr.com/index.html that claims to be the “Official webpage of the DPR of Korea”. Operated by

Alejandro Cao de Benos, from Spain, KFA is more likely North Korea’s commercial news dissemination and

public relations arm.

Within a seemingly voluntary space, networks of as many as 800 committees and other organizations of

sympathizers appear to be active around the world. Usually established by North Korean expatriates and

sympathizers, they cover a wide thematic and geographical range, as represented by the Committee for

Solidarity with Peoples in the World, the International Relations Committee for Reunification and Peace on the

Korean Peninsula, the Africa-Asia Solidarity Committee, the Women’s Association for Solidarity with Women

in Asian Countries, and the Arab and International Committee for Solidarity with the Korean People and for

Support of Korean Reunification.

3

The first Kim Il Jong Ideology Research Center and the Kim Jong Suk Revolutionary Struggles Study Group

(commemorating Kim Il Sung’s mother) were established in Tokyo, Japan and Peru respectively. Eventually,

over 30 affiliated centers were created across Asia, Africa, and Latin America.

JUCHE IN ASIA

North Korea’s use of Juche study groups as a tool to connect with thought leaders and emerging politicians

started with the Overseas Juche Research Center in Tokyo in April 1978. Funding for the center was provided

by the North Korean government but the Chochongryun, the Association of Chosonites in Japan (Pro-

Pyongyang Koreans in Japan), have taken over this responsibility. The organization is still going strong and in

2018, national representatives of the International Juche Ideology Institute celebrated its 40th anniversary in

Mongolia.

JAPAN

The year before, the Institute and the Kim Il Sung-Kim Jung Il Ideology National Research Network, also based

in Japan, held a seminar titled “National Juche Ideology Seminar for Independence and Peace.” In attendance

were Huh Jong Mang, President of the Japanese Chosun Association and Himori Humihiro, Head of the

Commission to Support Chosun’s Independent Peaceful Reunification, as well as many other Japanese social

scientists.

Japanese adherents to Juche are facing, unlike their counterparts in other countries, a stiff historical tailwind.

This is particularly the case, for example, when joined by pacifist Japanese promoters of the Murayama

Statement, the former Japanese Prime Minister Murayama's proclamation on August 15th, 1995 of deep

remorse over Japanese WWII acts. This position is, of course, unpopular in Japan and was reversed by the

current Prime Minister, Shinzo Abe.

INDONESIA

A prominent example of far less conflicted Juche influence evolved once North Korea pivoted towards China

and away from the Soviet Union in the early 1960s. At the same time, Indonesia, under its first President,

Sukarno, closed ranks with Communist China and, inevitably, with China’s Korean friend, Kim Il Sung.

Towards the end of 1963, Indonesia and North Korea entered into a range of bilateral agreements to strengthen

trade, engaged in technical, scientific, and cultural collaborations, and established diplomatic relations. Visits

by Sukarno to Pyongyang, and subsequently by Kim Il Sung to Jakarta, bolstered Sukarno’s confidence in North

Korea’s course of action under the Juche philosophy.

Sukarno integrated Juche principles into his policies and popularized the North Korean philosophy under the

Indonesian term “berdikari”. Progress was, however, suddenly interrupted when a coup, and soon after, a

counter-coup, ensued that sidelined Sukarno. His successor, Suharto, shifted Indonesia’s foreign policies while

maintaining his approach to North Korea. Still, the country’s short period of enchantment with Kim Il Sung

and North Korea soon faded in the memory of many Indonesians.

Indonesia’s government appears to prefer an engagement with, rather than a policy of isolation from, the

government in Pyongyang. The President of the Supreme People’s Council of the Democratic People’s Republic

of Korea, Kim Yong-Nam, met in 2002 with Indonesia’s President Megawati Soekarnoputri, attended the Asian-

African Conference Commemorative in 2005, and again paid an official visit to Jakarta in 2012 to President

Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono. While the visit prompted protests by Indonesia’s human rights and democracy

advocates, Jakarta's attitude toward Pyongyang changed only in 2014 when Widodo was elected President and

after the assassination of Kim Yong Un’s stepbrother Kim Jong Nam in neighboring Kuala Lumpur.

Acting within its traditional leadership role of the Non-Aligned Movement - of which the DPRK is also a

member - including active diplomacy with the DPRK, the Indonesian government is not neglecting its UN

membership obligations. It has detained a suspect North Korean ship and is prosecuting its captain. The

4

government in Jakarta has also reported an Indonesian dealer who, among other sanctions-contravening

activities, was also involved in the establishment of a Korean Cultural Centre in West Java.

While Juche has clearly lost some of its revolutionary glamour, it has not vanished entirely, nor have views on

North Korea turned entirely negative. Only 29 percent of Indonesians expressed in a 2013 BBC World Service

Poll a negative perception of the DPRK. The Sukarno Center still remembers Kim Il Sung fondly. In Summer

2015, it awarded its annual prize for global statesmanship to the grandson of the founder of North Korea, the

current leader Kim Jong Un.

VIETNAM

In contrast to Indonesia, the North Vietnamese did not fall for Kim Il Sung’s Juche philosophy and adhered

to their own leader, Ho Chi Minh, and his thoughts about how to fight the war against Western superpowers

while developing Vietnamese society. Ho Chi Minh’s prominence did not, however, stand in the way of a close

friendship with North Korea and Kim Il Sung. North Koreans even fought along with the Vietcong against the

US.

This comradeship gradually turned into rivalry over North Vietnam’s policy to pursue peace negotiations with

the US and its rejection of the China-DPRK attempt to coordinate the five Asian revolutionary states, China,

North Korea, North Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia.

Adopting Đổi Mới (Doi Moi) - policies that facilitate a market economy in a socialist system – Vietnam has

since rapidly transitioned into a post-conflict, socialist one-party ruled success story. With its Gross Domestic

Product currently at around USD 220 billion, Vietnam keeps rising through the ranks of the middling Asian

economies. North Korea, on the other hand, lingers in the bottom group but keeps indulging in the build-up of

one of the world’s largest military-industrial complexes. Despite their differences, both countries have resumed

friendly relations and the Vietnamese are, next to the Chinese, the largest group of expatriates living in North

Korea.

Now, with the evident success before their eyes, visiting North Korean diplomats appear ready to pragmatically

embrace Vietnamese principles. DPRK’s Foreign Minister Ri Yong Ho said, during a recent tour through

Vietnam’s industrial, economic and tourist centers, that the DPRK wants to learn Vietnam’s Doi Moi.

SINGAPORE

Singapore is perhaps the most unique of the DPRK’s Asian partners in that it is not only impervious to

Juche, but also a powerful and successful capitalistic contradiction of everything that Juche stands for while

maintaining the best of economic relations with many North Koreans. In 1967, shortly after Singapore was

expelled from the Malaysian Federation and was still a fledgling and unstable mini-state, it authorized North

Korea to establish a trade office. While commerce between the two countries quickly prospered, Singapore

established only in 1975 diplomatic relations with the DPRK - the first communist country to formally agree to

establish an embassy in Singapore.

Although the official trade volume was never very significant, it soon covered a broad palette of Korean raw

materials and manufactured products. While economically not very significant, for Singapore, the ability to

import sand from North Korea enabled the country’s critically important land reclamation projects.

In exchange, Singapore has always provided high-quality services to North Korean clients, including the alleged

financing and development of major portions of Pyongyang’s modernization. Allegations are frequently raised

in international media, that North Korea obtains access to embargoed commodities, specifically petroleum

products, through Singapore-based companies; or that they arrange for shipments of arms to and from the

DPRK.

5

Most recently, a new UN sanctions monitoring expert report alleged that a Singapore-based firm facilitated the

export of luxury goods to North Korea, which is banned under UN sanctions.

The Choson Exchange, based in Singapore but formed by students from prominent Western universities, such

as Harvard, Yale and the Wharton School, and Singaporean universities, offers a unique program to facilitate,

according to its website, “positive change and a healthy civil society.” The Exchange’s international practitioners

provide workshops, internships, mentorships and scholarships to entrepreneurs and business-minded North

Koreans. This unique not-for-profit example demonstrates that, even with Juche, North Koreans’ skill

requirements are far from being met.

OTHER ASIAN NATIONS

As recently as February 2019, the Asian Regional Committee for the Study of Juche held an event at Delhi

University. Generally, however, Juche activities in Asian nations appear to have abated in recent years and may

have come to a halt.

YEMEN

The Republic of Yemen recognized the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea in 1963. It was the third Arab

country to recognize the DPRK after Algeria and Egypt. The independence of Southern Yemen in 1967 and

the declaration that it was a communist system pushed the country to approach Pyongyang to establish closer

relations. The Yemen-North Korea alliance was born out of South Yemen’s history of communist rule.

Yemen bought ballistic missiles from North Korea in 2000 and evidence of the existence of Korean Scud

missiles used by Houthi rebels emerged during the recent Saudi-led war in Yemen.

Other sources have reported that North Korea sold missiles to Yemen and sent missile engineers to that country

in the 1990s.

In July 29, 2015, a South Korean intelligence official announced that Yemeni rebels had purchased 20 Scud

missiles from North Korea. These missiles were subsequently fired into Saudi Arabia in response to Saudi

aggression in Yemen. While Saudi Arabia initially believed that these missiles were from Iran, a former North

Korean security official confirmed South Korean intelligence claims in an interview with the Seoul-based news

agency Yonhap.

The Yemen-North Korea partnership is based on a combination of the DPRK’s desperate need for foreign capital

and Yemen’s insatiable thirst for arms to combat instability at home. North Korea also backed South Yemen’s

secession attempt in the 1994 civil war. According to a defected North Korean security expert, the DPRK

sold missiles to Yemen during the 1990s and even sent missile engineers to help strengthen Yemen’s defensive

capacity.

North Korea attempted to thaw its relationship with President Saleh’s North Yemen-dominated regime during

the late 1990s and early 2000s. Yemen’s support for Saddam Hussein in the 1991 Gulf War created deeply

strained relations with the United States. North Korea therefore sought to capitalize on this mutual discontent.

Yemen was a viable market for North Korean arms at a time when the DPRK’s economy was ravaged by famine

and the aftershocks of the dissolution of the USSR.

In 2002, when Spain intercepted a ship carrying North Korean Scud missiles to Yemen, Yemen announced that

it would suspend all military linkages with the DPRK and justified its acceptance of North Korean weapons on

the grounds that it was fulfilling pre-existing contracts.

In August 2018, France 24 News Agency said: “According to a UN secret report, North Korea attempted to

supply small arms and light weapons (SALW) and other military equipment via foreign intermediaries to Libya,

Yemen and Sudan." It is believed that this foreign intermediary is Syrian.

6

The NDTV website reported that the Syrian arms trafficker was named Hussein Al-Ali who offered "a range of

conventional arms and in some cases ballistic missiles to armed groups in Yemen and Libya" that were produced

in North Korea. With Ali acting as a go-between, a "protocol of cooperation" between Yemen's Houthi rebels

and North Korea was negotiated in 2016 in Damascus that provided for a "vast array of military equipment."

The English version of Asharq Al-Awsat newspaper reported more information from the UN report, specifically

about Hussein Al-Ali: “Syrian civilians, including Ali, became involved in trafficking arms on North Korea’s

behalf. They attempted sales of traditional weapons and even ballistic rockets to Middle Eastern and African

countries, including armed groups in Yemen and Libya, charged the panel.”

AFRICA

Fueled by afro-centric and often socialist ideals, many African nations that emerged from colonialism into

independence in the late 1950’s were naturally predisposed to embracing North Korea’s Juche philosophy. But

the DPRK had even more to offer emerging, young African leaders. Their participation in Juche study groups

also led many aspiring African leaders to scholarships in one of North Korea’s universities, technical schools, or

military academies.

Kim Il Sung had very deliberately targeted and befriended the young leaders of Africa’s independence

movements with the calculation that some would become the first heads of the newly independent states.

Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana, Julius Nyerere of Tanzania, Robert Mugabe of Zimbabwe, and Gamal Abdel

Nasser of Egypt are merely some of the first-generation African leaders who revered Kim Il Sung for his strong

support.

Kim’s exploits as the leader of Chinese-Communist insurgencies against the Japanese occupation of Manchuria,

regardless how exaggerated by Mao’s propaganda, and his leadership of North Korea facilitated by the Soviet

Union made him a celebrated guerilla leader. With the release of his doctrines, in particular his 1955 Juche

speech, he also established himself as a leader independent from Maoism or the prevailing anti-Stalinist

reformists that prospered under Soviet Secretary General Nikita Khrushchev. His reputation among Africa’s

independence movements grew further when he started to sent North Korean fighters, military supplies

and tactical advisors to the Mozambique Liberation Front, Robert Mugabe’s ZANU-PF, and Angola’s

rebel movements. Even the formation and training of the elite Kamanyola Infantry Division of the Forces

Armées Zaïroises that would protect the rather reactionary Mobuto did not dent Kim Il Sung’s revolutionary

credentials.

Once the wars of independence were won, Kim continued his support of his African partners with the

formal establishment and training of military forces, technical assistance with land reforms, introduction of

agricultural technologies and development programs, or construction of sorely needed public infrastructure.

In the emerging world order of Kim Il Sung, the construction of an African resistance front against the West

was driven as much by the national security prerogatives of North Korea as by the opportunity to apply and

prove the validity of Juche. While his vision of diverting Western aggressors from his home turf in East Asia by

bolstering African revolutionary proxies worked, it was mostly because of Soviet and Mao Zedong’s support.

Perhaps because Juche is not easily identified with traditional Communism, it survived the end of the Cold

War and, even 50 years later, still has active devotees in Africa’s political landscape. Juche Africa, for example,

operates as a continental coordinator of diverse Juche-related activities and as a communication platform for the

government of Pyongyang. Headquartered in Kampala, Uganda, with Lt. Colonel Henry Masiko serving both as

head of the national and the continental organization, Juche Africa operates a schedule of events with a board of

representatives of at least 10 African countries.

7

Other websites, subsidiary and independent organizations, as well as conferences are indicators of how North

Korea’s thinking contributes to contemporary African political thought and dialogue. One example is the

website of Congolese (DRC) organizations Association Nationale des Études des Idées du Juche (Aneij) en

RDC.

A Juche Ideology Research Organization was established in Mali on April 15, 1969 and, on the same day in

1985, the African Regional Committee for the Study of the Juche Idea came into being in Freetown, Sierra

Leone. April 15 is the birthday of DPRK founder Kim Il Sung.

The official newspaper of the Central Committee of the Workers' Party of Korea, the Rodong Newspaper,

reported that a discussion panel titled “Democracy, Self-Sufficiency and Development” was held in Conakry,

Guinea, on November 3, 2018. In attendance were the Secretary-General for the African Regional Committee

for the Study of the Juche Idea, Andre Lohekele Kalonda; Alhassan Mamman Muhammed, Chairman of the

Nigerian National Committee for the Study of Kimilsungism-Kimjongilism (Kim Jong Il’s spin on Juche); and

Riyad Chaloub, Chairman of the Guinean National Committee for the Study of Kimilsungism-Kimjongilism.

The latter two heads are also directors of the African Regional Committee for the Study of the Juche Idea.

Subsequently, Andre Lohekele Kalonda was invited to North Korea to attend an International Symposium on

Korean Studies on November 18, 2017, where he presented a paper titled “On the Invincibility of Socialism in

Juche”.

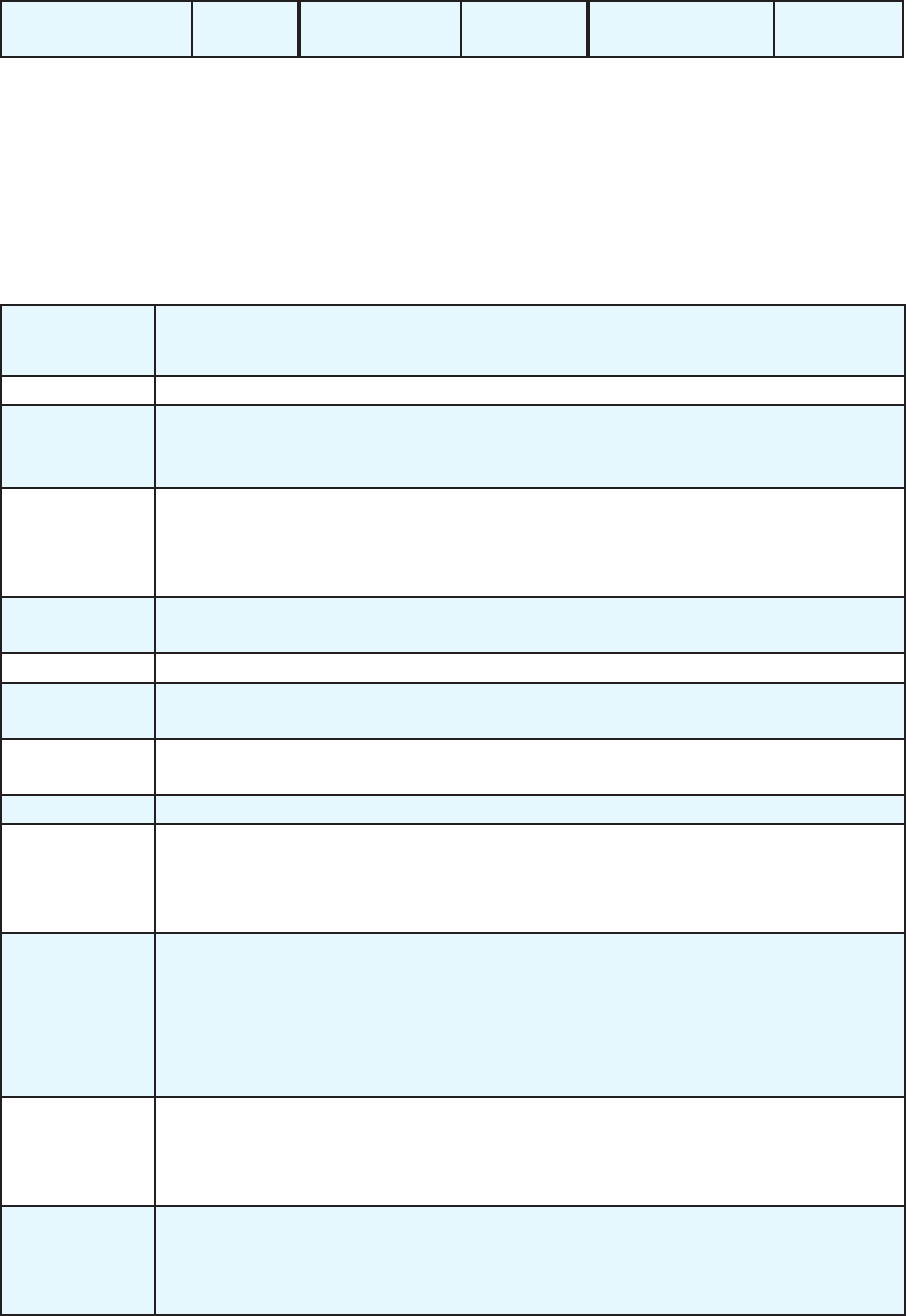

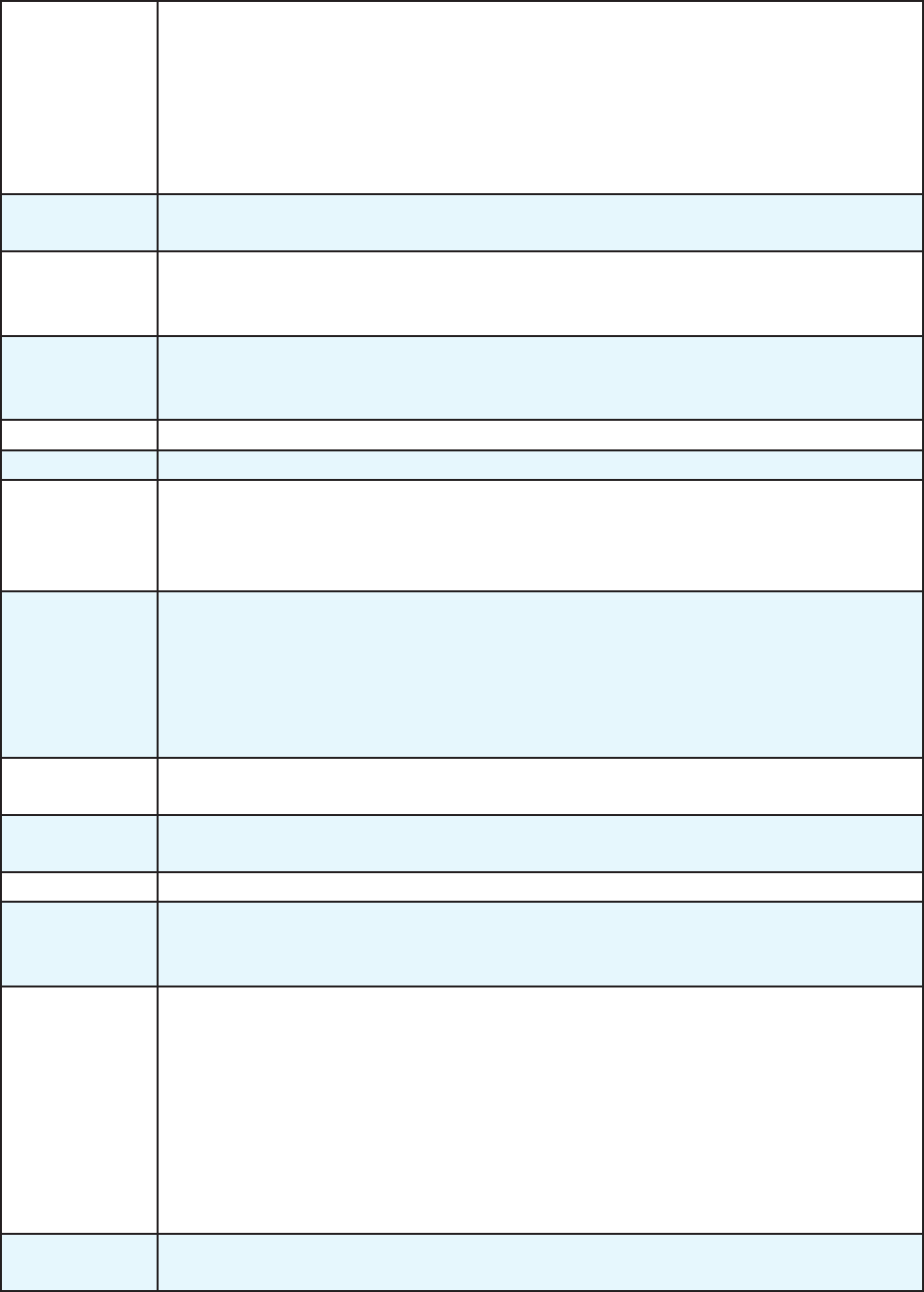

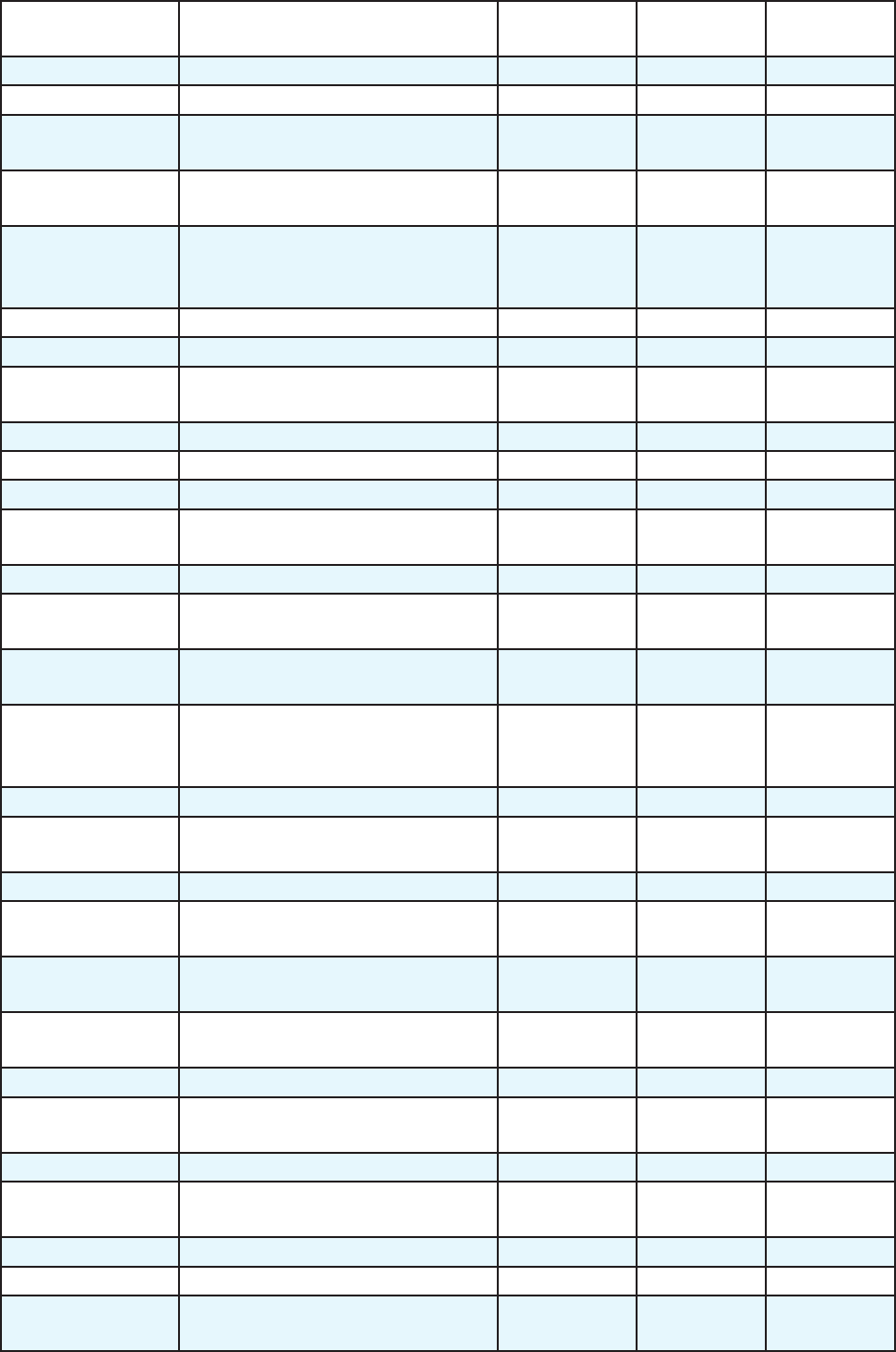

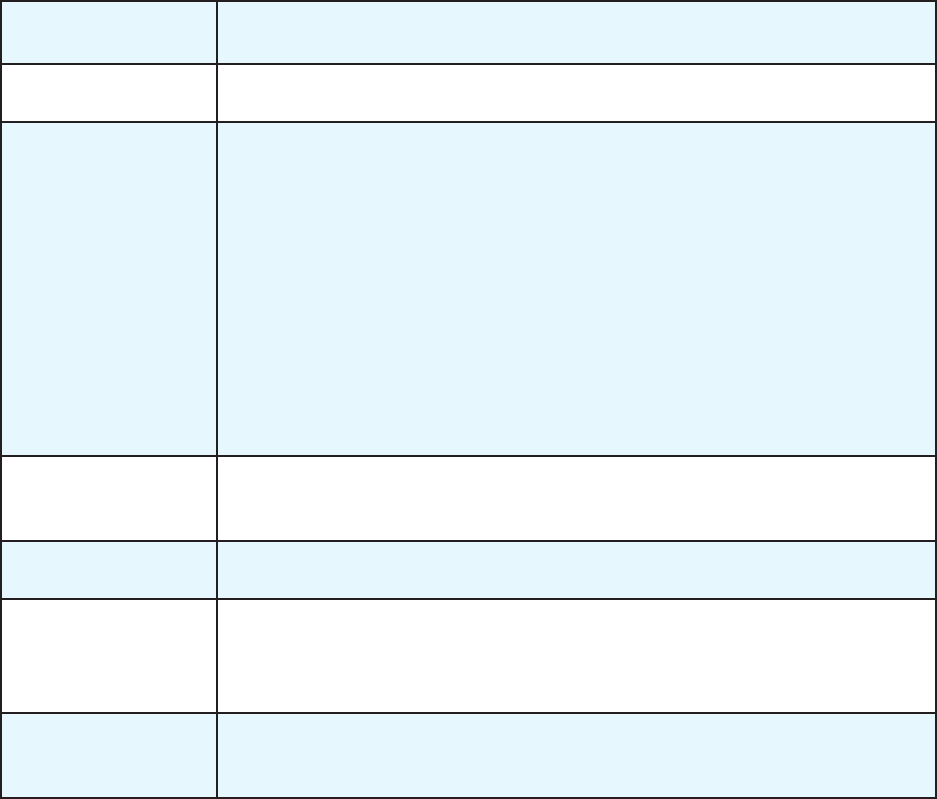

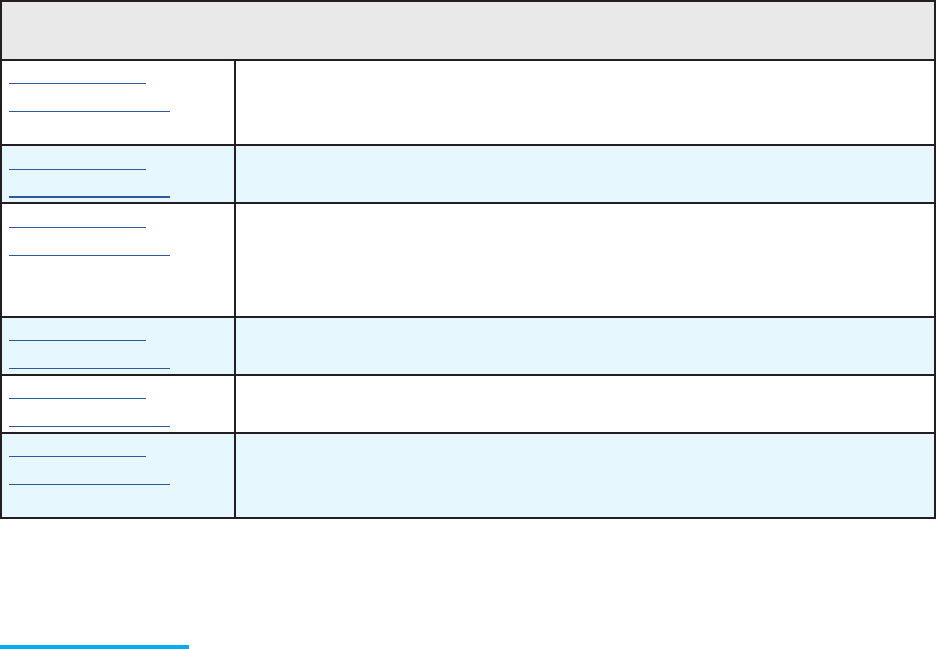

Table 1: Reported activities by African Juche study groups

COUNTRY ACADEMIC INSTITUTION RECENTLY REPORTED ACTIVITIES

Angola Blogs with the Arquivos AVCP

(files) is operated by Lenan Cunha

Several blogs, see here or here, offer news about the

latest developments in regard to North Korea and Juche

Benin Comité National Béninois d’Etude

des Idées du Juche

The group held a Regional Online Seminar titled The

Eternal Sun from June 1, 2017 to July 3, 2017. It is still

available.

Côte d’Ivoire Africa Songun Study December 23, 2018, Desire Koudson held a Songun

study meeting with representatives from Niger, Guinea,

Cameroon and South Africa.

Democratic

Republic of the

Congo

Juche Research Institute for

Independence

Association National des Études

des Idées de Juche (ANEIJ)

On February 8, 2018, a Juche institute was opened in

Kinshasa, DRC, called the Juche Research Institute for

Independence in Congo. It is the second of its kind in

DRC.

This group presents its papers on the Internet, for

example by its vice-president Gaston Otete Mboyo

about the revolutionary role of Juche for modern

Congo

Ethiopia Ethiopian Youth Study Group of

the Juche Idea

No activities reported

Nigeria Nigerian National Committee on

the Study of the Juche Idea

The Nigerian group maintains an active blog

Republic of

Congo

Association Congolaise D’Amitié

Entre les Peuples (ACAP)

A conference was held on April 13, 2017, at the

headquarters of the ACAP, in the presence of the visiting

President of the Supreme People's Assembly of the

DPRK, Kim Yong-nam, and André Massamba, Deputy

Secretary General of the Congolese Labor Party (PCT.

8

Tanzania National Coordinating Committee

on the Juche Idea Study Groups

The Coordinating Committee indicates that at least 13

different study groups are operating in Tanzania. This

group appears to publish actively over a French blog site

Uganda Ugandan National Committee for

the Study of the Juche Idea

The government of Uganda has allegedly disbanded

North Korean interest groups although it is not

confirmed that the Juche study group does not

informally continue its activities.

LATIN AMERICA REGION

Latin Americans have traditionally been interested in North Korea, its leaders, and their thinking. Juche

continues to be of interest across the continent, with Venezuela, unsurprisingly, currently taking the lead in

exploring and promoting the North Korean ideology. A Latin American regional seminar on independence and

global peace that took place in Maracay City, Aragua State, Venezuela, on October 5-6, 2018 brought together

not only the continental leaders of Juche institutes, including those from Mexico, Brazil, Chile, Peru, Ecuador,

Colombia and Costa Rica, but also North Korean diplomats and representatives of the Pyongyang government.

In early February 2019 a similar event, “The Struggle for Self-dependence and Peace in the World," took place

in Mexico City to discuss with members of the Mexican parliament and members of the National Committee

for the Study of the Juche Idea in Japan. Alongside similar pro-DPRK sentiments, the Costa Rica Juche study

group released in early January a joint statement by national and regional representatives in support of Supreme

Leader Kim Jong Un's New Year Address. Around the same time period, the Chairman of the Brazilian

National Committee for the Study of Juche visited Pyongyang, its factories and cultural centers. Subsequently,

he released a statement full of adulation for Kim Jon Un’s leadership.

Risks of global trade and DPRK sanctions violations

With the global integration of commerce, no government and almost no company can afford to operate

without a heightened awareness of trade and security risks. Because of the multifaceted North Korean threats

to international security, particularly complex and multidimensional sanctions countermeasures have to be

applied. To comply with these measures, even the best-intentioned implementation and compliance officers will

be tested by the required magnitude of assiduous due diligence.

The complications result from several factors. First, the international sanctions architecture is complex in any

case. Second, the North Korea sanctions with consecutive resolutions adopted over the past 12 years, are more

diverse than any other sanctions regime. Third, special expertise is required to keep track of frequent technical

amendments to the lists of restricted components, machinery, or dual-use items.

The political consequence for many states that used to maintain fairly accommodating relations with the

DPRK often led to a review of existing diplomatic and economic arrangements. While UN sanctions did not

require abandoning diplomatic or economic relations, they require closer scrutiny of compliance by accredited

DPRK diplomats with the Vienna Convention that regulates the privileges of diplomats. Economic relations

are increasingly constrained by many restrictions including commodity trading bans, restrictions on financial

services and service providers, in particular the transfer of revenues or other funds to and from the DPRK or

North Korean owned businesses.

An example of how relatively modest revenue sources were indirectly affected is the chain of Pyongyang Raeng

Myun Restaurants operated in Cambodia. As North Korea’s proliferation activities triggered rejection even

in traditionally friendly Asian countries and business receded, half of the restaurants had to close while the

remaining restaurants were relaunched as Chinese restaurants.

9

In the meantime, Cambodia’s Minister of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation, Prak Sokhonn, was

pursuing a more balanced policy towards North Korea, repeatedly declining to meet with high-ranking DPRK

diplomats and pressing for the resumption of the Six-Party Talks and full compliance with all UN sanctions. At

the same time, however, Cambodia entered into a joint venture with Mansudae Overseas Projects Group for

the construction of the Angkor Panorama Museum in Siem Reap. The venture gave the North Korean company,

which is under UN sanctions, a share in the revenue stream generated by the museum.

This is similar to the situation in Malaysia, a country that for historic reasons was never particularly warm with

North Korea. When North Korean assassins eliminated Kim Jong Nam in Kuala Lumpur airport in February

2017, allegedly because Kim Jong Un perceived his stepbrother as a threat to his rule, diplomatic relations

between the two countries were frozen. The respective embassies were closed, and for a period, all diplomatic

interactions stopped.

The interruption was, however, short-lived. With the election of mercurial President Mahathir Mohamad,

a re-engagement, including the reopening of Malaysia’s embassy in Pyongyang, was announced. During the

November 2018 ASEAN Summit meeting and again during the East Asia Summit, he recommended the

relaxation of economic sanctions on North Korea. In Mahathir’s opinion, the loosening of sanctions would serve

as a “reward” in exchange for North Korea’s denuclearization steps envisioned during Kim Jong Un’s meeting

with US President Donald Trump on June 12, 2018 in Singapore.

Philippines President Rodrigo Duterte has changed his attitude towards North Korea from calling Kim Join Un

a “fool” to “my idol” or “my hero”. Since It used to be the

third largest trading partner of the DPRK, the Philippines may likely be entangled with deliveries of electrical

and industrial machinery, including parts for centrifuges, while Philippine counterparts import North Korean

iron and steel products – all potential violations of UN sanctions.

North Korea’s most infamous export of conventional arms is unproblematic from a UN sanctions point of view

because it took place in 1973 – during and after the Yom Kippur war with Israel. Egypt had already requested

an emergency supply of North Korean arms during the six-day war in 1967. The war ended so quickly,

however, that there was no time to start the requisite formalities for an arms transfer, although North Korea

sent soldiers and pilots to Syria and combat training officers to the Palestinian Liberation Organization. The

1973 Yom Kippur War allowed North Korea to train Egyptian military officials and dispatch pilots and missile

technicians to Egypt.

The relationship between Egypt and North Korea prospered and, a few years later, an Egyptian-owned tactical

ballistic missile, liquid rocket R-17 (better known as the SCUD-B missile) was reverse-engineered. Based on

this technology, the North Koreans soon developed the Hwasong-5 missile that they sold to Egypt and many

other states.

From a UN sanctions perspective, none of these trades are problematic. The special DPRK-Egyptian

relationship would eventually lead to one of the more serious cases of sanctions violations when 30,000 North

Korean rocket-propelled grenades were discovered in 2016 on board a ship en-route to Egypt.

Algerian authorities used their historically friendly relations with North Korea for a far more laudable effort in

May 2018. Out of a shared anti-imperialism when Algeria was still ensnared in its struggle for independence,

North Korea had supported the National Liberation Front (NFL). When Algeria became an independent

country with the NFL as its dominant political party, Algeria agreed as the first non-socialist country to

formalize diplomatic relations with the DPRK.

But the realities of international nonproliferation politics caught up with these old friends when Algeria

joined the Non-Proliferation Treaty and therefore had to oppose North Korea’s illegal proliferation projects.

10

Building on its friendly relations, Algeria’s Foreign Minister Ramtane Lamamra attempted to facilitate bilateral

cooperation in recent years when North Korean Vice-Minister of Foreign Affairs, Shin Hong Chul, was visiting

Algiers. Subsequently, Algerian Secretary General of Foreign Affairs, Hassan Rabehi and Shin convened in

Algiers the First Conference on Political Negotiations that also led South Korea's ambassador to Algeria, Park Sang

Jin, to invite his North Korean counterpart, Choi Hyuk Chul, to his home in Algiers.

However, not all bilateral contacts seemed to achieve the results of North-South mediation, as the example of

the long-term relationship between North Korea and Madagascar shows. Having been a staunch ally of North

Korea for many decades and recipient of economic support, Madagascar declined to participate in the 1988

Seoul Olympics. Eventually the relationship cooled and Madagascar embraced a more balanced approach to the

two Koreas.

North Korean diplomats and Foreign Ministers frequently visit francophone African countries, such as the

August 2013 visit by Park Eui Chunto to Benin’s President, Thomas Yani Boni. In 2013, the North Korean

Foreign Minister, Pak Ui Chun, visited his Cameroonian counterpart, Minister of External Relations, Pierre

Moukoko Mbonjo.

While these contacts served to strengthen existing friendly relations, some francophone African countries

have turned away from North Korea, as the example of Côte d’Ivoire shows. Since the early 1990’s, no North

Korean ambassador has been based in Côte d’Ivoire, and the diplomat representing the DPRK is based in

Nigeria but has never presented credentials to the Ivoirian government. The Republic of Congo has undergone

several changes to arrive at its current balanced diplomatic ties with both Koreas.

Notable exceptions in North Korean-African relations are Djibouti and Morocco. Both francophone countries

do not currently maintain bilateral diplomatic relations. Morocco’s stance may be affected by North Korea’s

historic military and logistics support to the anti-Morocco insurgencies of the Popular Front for the Liberation

of Saguia el-Hamra and the Río de Oro (Polisario) in West Sahara.

II. North Korea’s Military Diplomacy and UN Sanctions

Education and training

North Korea’s initial successes within the large group of members of the Non-Aligned Movement was based

on shared anti-colonial, anti-imperialist values and the creation of Friendship and Juche Study groups brought

young political, military, and business leaders within its ambit. Some of these emerging elites had already

benefited from bilateral educational programs at North Korea’s universities. The Hermit Kingdom’s sociability

was clearly designed to elicit long-term sympathies and loyalties.

Within 20 years of having achieved independence, more than half of all new Asian and African nations had

established diplomatic relations with North Korea and, in many cases, friendship and limited trade agreements.

Benin, China, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Indonesia, Egypt, Mozambique, Namibia, Nigeria,

Libya, the Republic of Congo, Russia, the Seychelles, Uganda, Vietnam, and Zimbabwe all benefited from

North Korea’s education offerings. In the 1980s, approximately 200 students from Guinea, Equatorial Guinea,

Tanzania, Madagascar, Zambia, Lesotho, Mali, and Ethiopia were selected by their respective governments to

study in North Korea. The students were dispersed to different schools and universities depending on their field

of study.

11

Even today, despite massive international sanctions pressures, approximately 100 foreign students are

matriculated at the Kim Il Sung University in Pyongyang. It is no surprise that Juche remains the centerpiece of

the University’s curriculum when its website advertises: “Kimilsungism-Kimjongilism is a great revolutionary

ideology whose idea, theory and method of Juche have been systematized integrally.”

Supply of military goods and services

Foreign students interested in military careers would find particularly competent training offered by war-

seasoned officers turned military instructors at North Korea’s premier military academies. Asian, African and

Latin American resistance fighters and, in some cases their children, would receive training. Francisco Macias

Nguema, Equatorial Guinea’s rebel leader and first President who was eventually executed, arranged for his

family to escape to Pyongyang. His daughter Monique Macias received schooling and military training, as she

eventually described in her memoirs I'm Monique, From Pyongyang.

Military education habituated the cadets to North Korean arms. In many instances, once the cadets returned

home and rose to positions of influence, they became clients of DPRK’s military supplies. In parallel to its

diplomatic and educational initiatives, North Korea’s capacity for the manufacture of defense equipment and

professionalized service standards also expanded. A study from 1983 concluded that “about 450 confirmed

North Korean military personnel were assigned overseas, primarily in Africa.” Its greatest successes, the study

stated, were with the training of security forces for VIPs. The required trust VIPs were willing to extend was

indicative of how the DPRK had succeeded to position itself as a revolutionary friend.

Most of these advisors were stationed in places where Pyongyang had succeeded in delivering North Korean

manufactured arms. At the time, about 20 countries were identified as recipients of DPRK military supplies

and related training. The following states were reported to have participated in the DPRK’s oversea military

sales and support activities:

• Benin

• Burundi

• Burkina Faso

• Cuba

• Egypt

• Ethiopia

• Grenada

• Guyana

• Iran

• Jamaica

• Libya

• Madagascar

• Malta

• Nicaragua

• Pakistan

• Rwanda

• Seychelles

• Somalia

• Surinam

• Syria

• Tanzania

• Uganda

• Zambia

• Zimbabwe

The most controversial North Korean military support programs that at times turned out to be self-defeating

for its overall diplomacy were the supply of military matériel and training to armed non-government,

insurgency, and terrorist groups. In addition to supporting the Palestinian Liberation Force (PLO), and the

Red Army Faction, the DPRK also supplied and trained extremists in Argentina, Chad, the Central African

Republic, Ghana , Mauritania, Mexico and Sri Lanka. In other words, governments supported by North Korea

since their earliest post-colonial days suddenly had to confront insurgencies armed with North Korean weapons.

THE RAPID EXPANSION OF SANCTIONS MEASURES

The Security Council has created the most complex set of restrictions that the UN has ever applied on any

state with nine sanctions resolutions operating concurrently. They do not only target North Korea’s build-

up of weapons of mass destruction; they also prohibit trade in conventional arms and many commodities and

luxury goods, curtail access to the assets of individuals, companies and entities, restrict maritime and aviation

transport, prohibit the hiring of North Korean workers abroad, and even restrict certain educational services.

12

Despite these challenges, the nations elected to the Security Council have consistently voted in favor of

sanctions resolutions on the DRPK. The most significant expansions of sanctions measures came to a vote

with resolutions 1718 (2006), 1874 (2009), 2087 (2013) 2094 (2013), and 2270 (2016). They were adopted

unanimously, including states that have maintained friendly relations with the DPRK:

• Angola

• Argentina

• Austria

• Azerbaijan

• Burkina Faso

• China

• Congo

• Costa Rica

• Croatia

• Denmark

• Egypt

• France

• Ghana

• Greece

• Guatemala

• Japan

• Libyan Arab

Jamahiriya

• Luxembourg

• Malaysia

• Mexico

• Morocco

• New Zealand

• Pakistan

• Peru

• Qatar

• Republic of Korea

• Russian

Federation

• Rwanda

• Senegal

• Slovakia

• Spain

• Togo

• Turkey

• Uganda

• Ukraine

• United Kingdom

of Great Britain

and Northern

Ireland

• United Republic

of Tanzania

• United States of

America

• Uruguay

• Venezuela

• Viet Nam

Reported contraventions of UN sanctions

With the introduction of UN sanctions on North Korea in 2006, the count of recipient countries as well as US

Dollar volumes of its military programs diminished. Many countries that maintained friendly relations with the

DPRK were caught unawares by both the accelerating speed and the scope of sanctions adopted by the Security

Council. Evolving prohibitions against the import and export of North Korean military matériel supplies and

training, including small arms and light weapons, alongside the curbing of North Korea’s diplomatic privileges

and commodity trading, had an immediate impact on many nations’ interests. Nevertheless, some countries still

received materials (see table 2), mostly because of pre-existing contractual obligations.

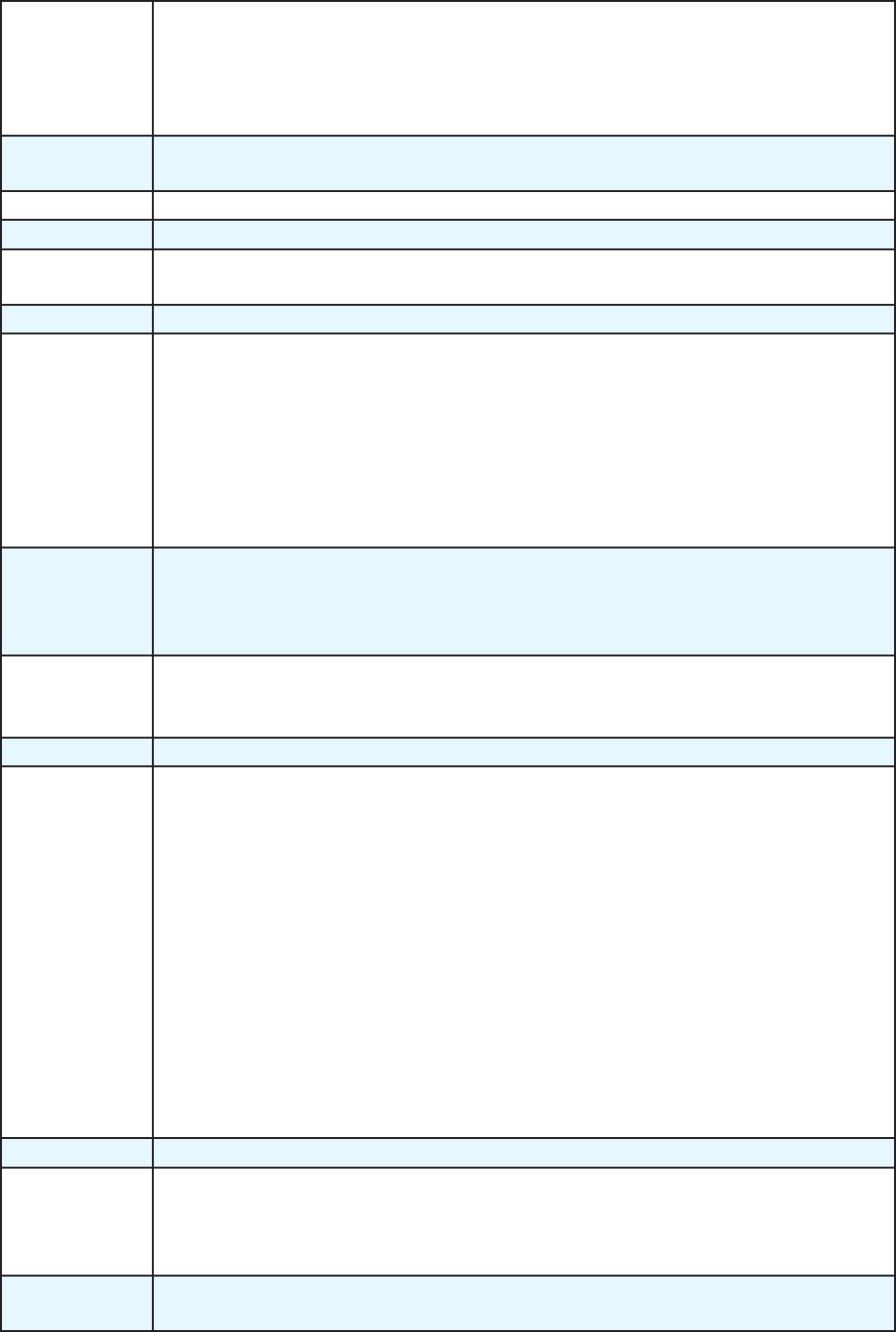

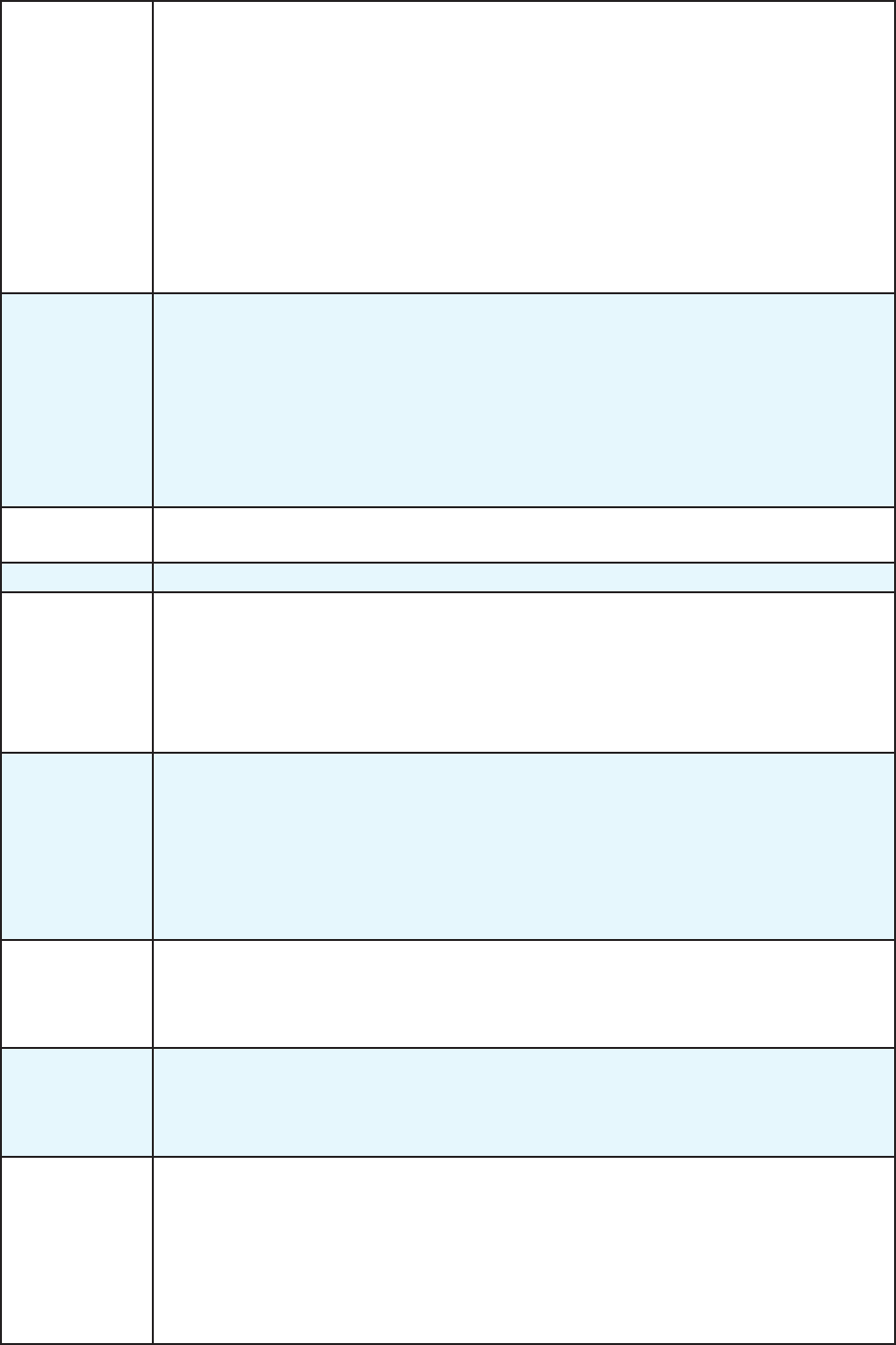

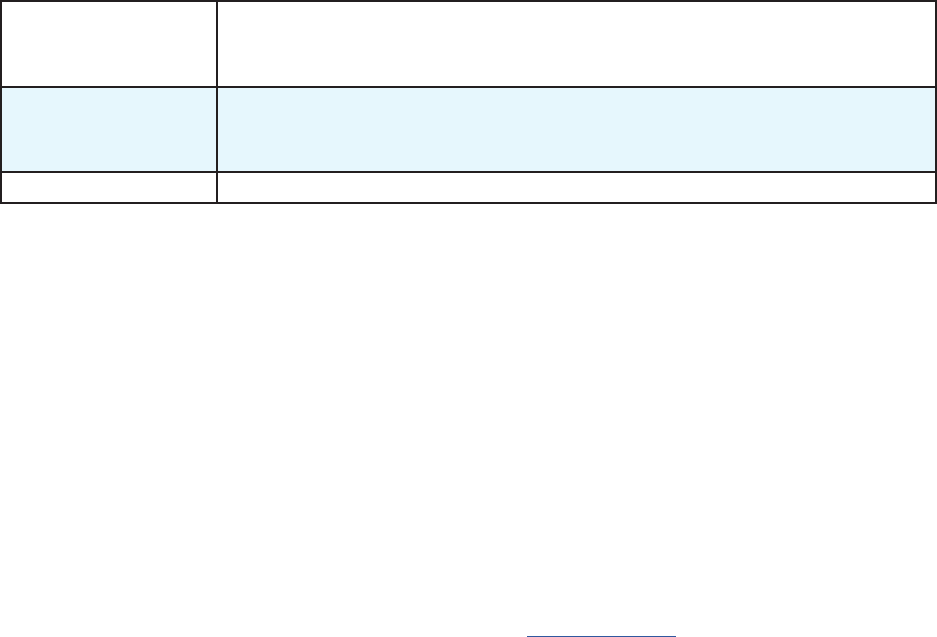

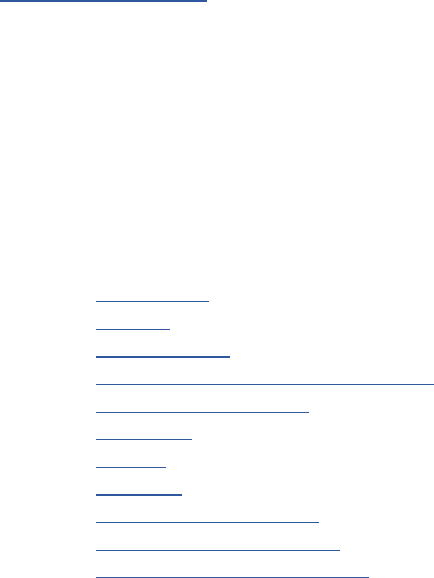

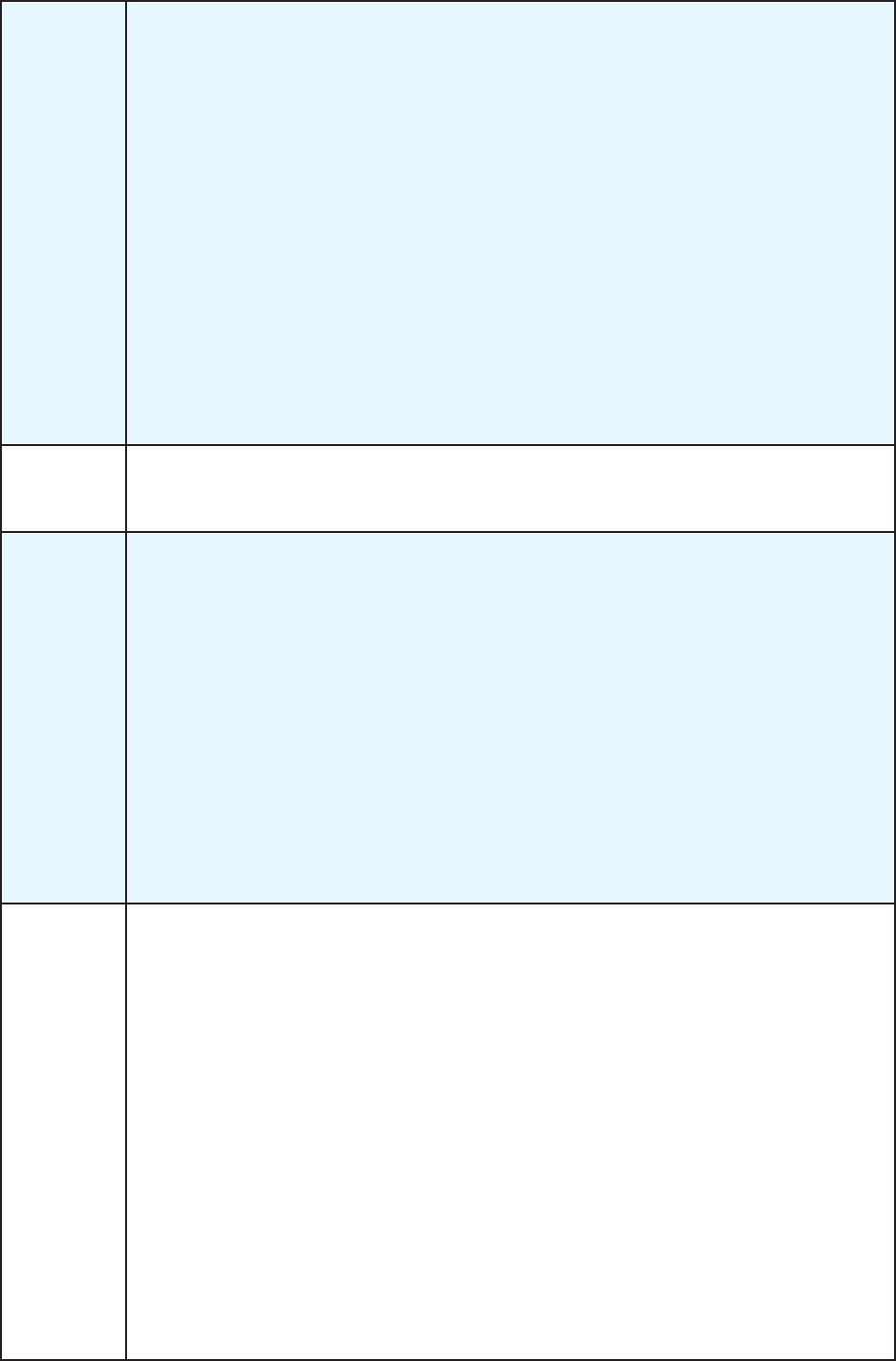

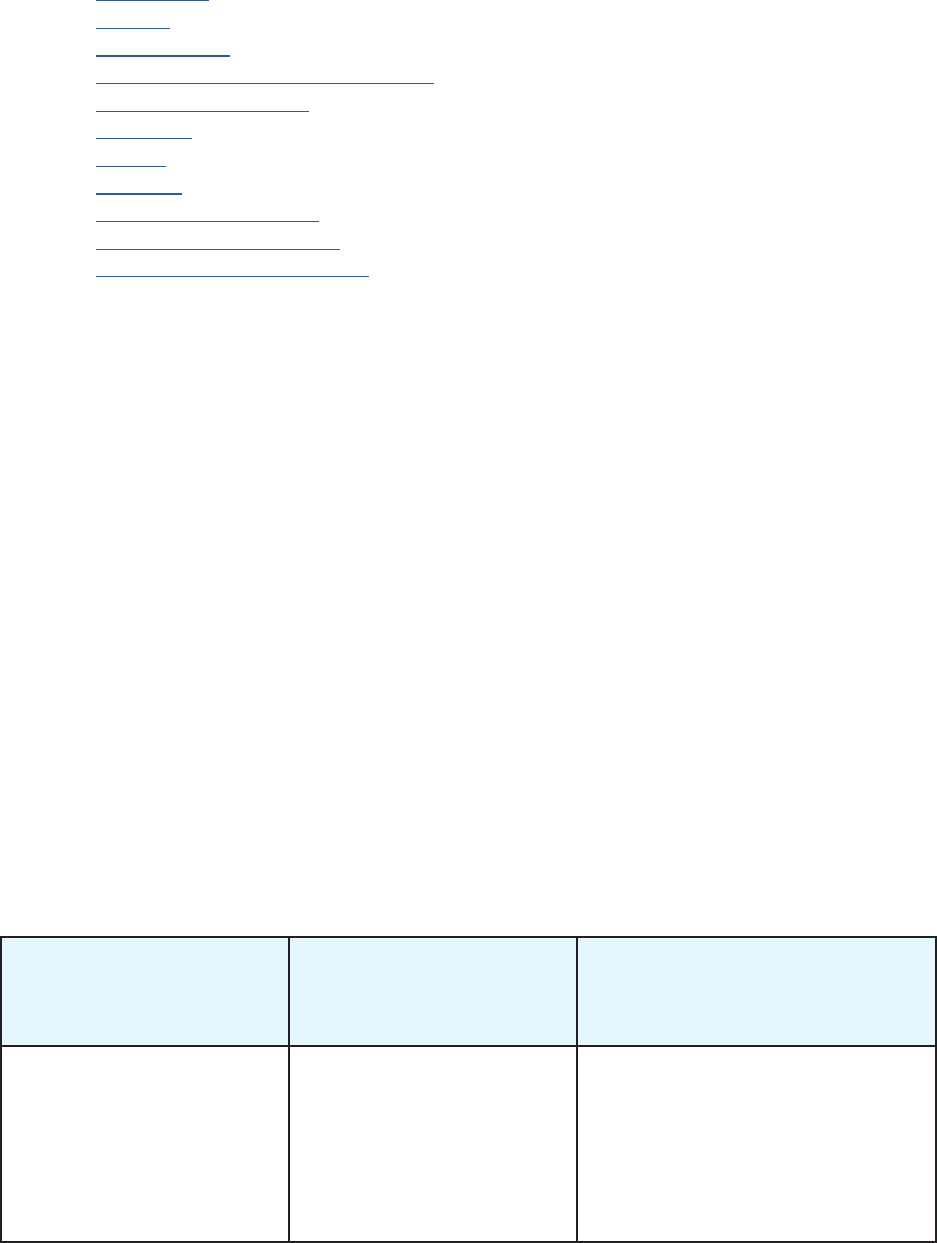

Table 2: Expenditures for DPRK supplies and training

YEAR - COUNTRY

VALUE

USD

YEAR -

COUNTRY

VALUE

USD

YEAR - COUNTRY

VALUE

USD

2017

El Salvador

59 858 2011

Austria

159 2009

Antigua / Barbuda

619

2016 - Niger 37 491 2011

Bahrain

233 2009

Colombia

3 381 264

2015

Trinidad / Tobago

38 659 2011

Chile

156 2009

Thailand

117 207

2015

French Polynesia

4 457 2011

Colombia

37 426 2009

Egypt

917

2014

Sri Lanka

102 2011

Fiji

37 570 2008

Fiji

561 271

2014

France

529 2010

Colombia

1 723 594 2008

Thailand

13 630

2012

Trinidad / Tobago

12 207 2010

New Caledonia

4 731 2007

Brazil

45 500

13

2010

Spain

1 773

UN EXPERT REPORTS

With the establishment of the UN panel of experts for the DPRK in June 2009, a continual drip of facts

and descriptive material about North Korea’s potential sanctions violations entered public awareness. The

reported transactions involve mostly trade in military goods and related assistance and construction services.

Increasingly, the trade in commodities has also caught the attention of the Security Council.

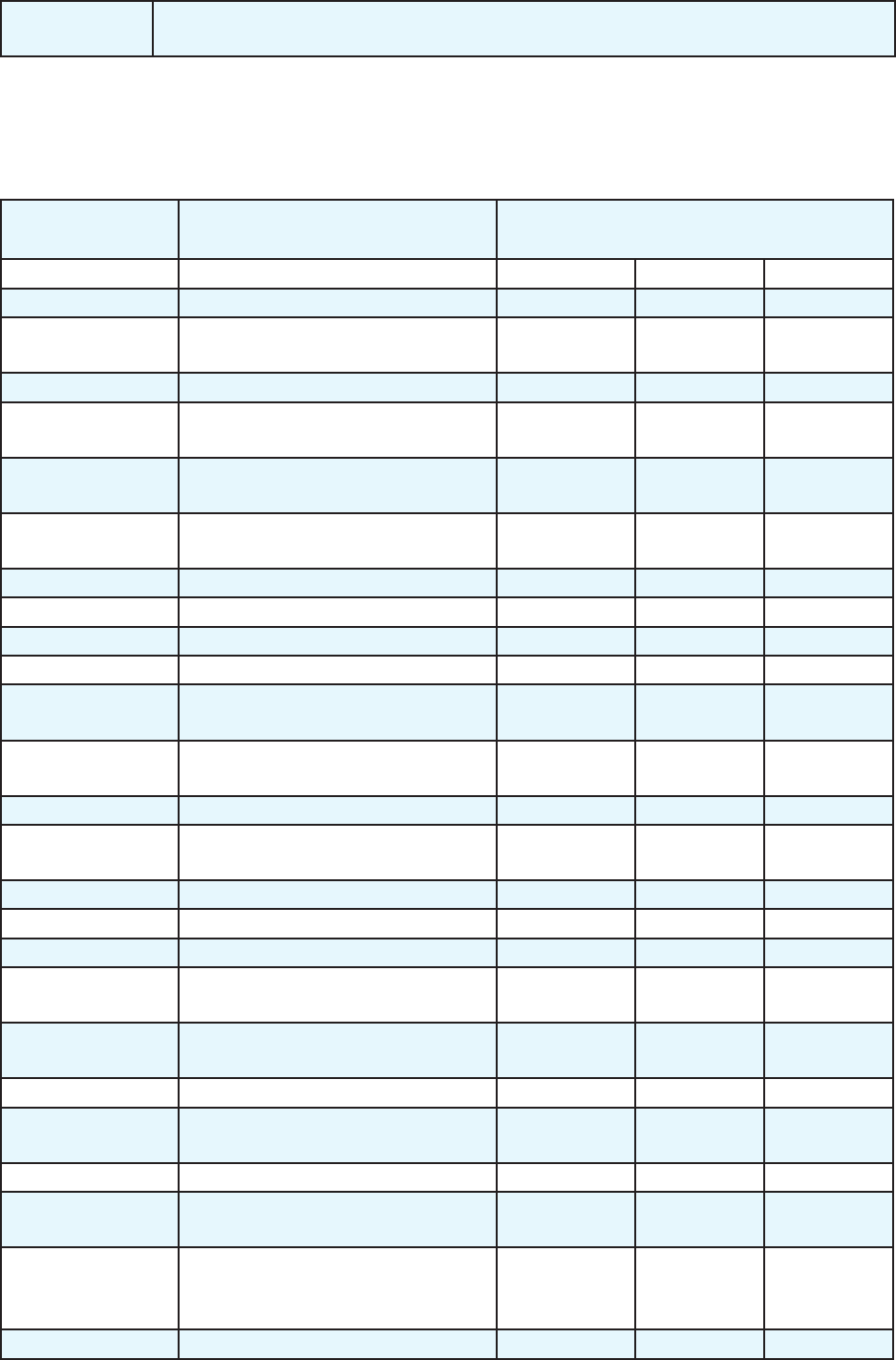

Table 3: Attempted and successful sanctions violations

COUNTRY PROJECT OR MILITARY MATÉRIEL

Algeria Mansudae Overseas Project Group of Companies

Angola Refurbishment and spare parts for military patrol boats; Training of the presidential guard;

refurbishment of naval vessels; various statues and buildings.

Inconclusive: Presence of 80 Military advisors travelling to Mozambique;

Australia Brigt Australia, a Sydney based subsidiary of Jilin Brigt (China) was investigated over

its alleged involvement in helping DPRK circumvent sanctions for a $770,250 coal

shipment from DPRK to Vietnam in 2018. Livia Wang, director of Brigt Australia, was also

investigated for falsifying documents stating that the coal came from Russia.

Benin Statue of Behanzin; cultural institution; printing factory;

alleged military and police training

Botswana Three Dikgosi monuments in Gaborone

Burkina Faso Revolutionary Torch Monument; outdoor theater;

five small water reservoirs

Burma Allegations about DPRK assistance to enable a Burmese nuclear arms program, including

construction of tunnel systems.

Burundi Heavy machine guns

Cambodia Mansudae Overseas Projects Group built the Angkor Panorama Museum in Siem Reap,

Cambodia. The museum cost around 22-24 million USD and the profits from the sale of

tickets, souvenirs and the cafe will be split between the museum operator and Mansudae.

Jie Shun, North Korean vessel, sailed under the Cambodian flag.

China Multiple procurement and transshipments of prohibited materiel, proliferation items, and

commodities facilitated by Chinese companies;

Activities of Namchongang Trading Corporation, Namhung Trading Corporation and

associated front companies and their representatives; procurement of items used for nuclear

programs, including pressure transducers and vacuum equipment from Shanghai Zhen Tai

Instrument Corporation Limited.

Democratic

Republic of

Congo

Military training of and supply of 9-mm firearms for the presidential guard; statue of the

Congo’s first elected president, Patrice Lumumba and former President Laurent-Desirée

Kabila; possible Saeng P’il, (a.k.a. Green Pine Associated Corporation) investment in

Medrara gold mine

Egypt Scud spare parts: connectors, relays, voltage circuit breakers, barometric switch; Attempted

delivery of 30,000 PG-7 Rocket-propelled grenades and components; limonite (iron ore);

DPRK diplomat An Jong Hyok attempt to negotiate on behalf of Saeng Pi’l Trading

Corporation (Green Pine Associated Corporation) the release of the vessel Jie Shun.

14

Eritrea Turret milling machines; Vertical milling machines; Slotting machines; military radio

communications product and related accessories: high-frequency software defined radios;

Crypto-speaker microphones; GPS antennas; high-frequency whip antennas; clone cables;

camouflaged rucksacks and carry-pouch; presence of Green Pine Associated Corporation

and possible involvement of Glocom.

Equatorial

Guinea

Stadium, conference hall

Ethiopia Tiglachin Monument in Addis Ababa.

Gabon Statue of President Omar Bongo

Germany Attempted procurement of a multi-gas monitor (prohibited dual-use item). Abuse of

diplomatic privileges by Ri Yun Thaek (a.k.a. Ri Yun Taek)

Guinea People’s Palace;Kim Il Sung Agricultural Sciences Institute

Indonesia DPRK vessel’s Wise Honest trans-shipment of 25,500 tons of coal, sailing with Automatic

Identification system (AIS) turned off in Indonesian waters, and using a false flag. Recipient

was alleged to be ROK-based company Enermax. However local brokers by the name

Hamid Ali and Eko Setyatmoko had coordinated on behalf of and with Jakarta-based DPRK

diplomats and Jong Song Ho, of Jinmyong Trading Group and Jinmyong Joint Bank of the

Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, who also acted as part of “the establishment of a

Korean Cultural Centre in West Java”.

Iran Alleged activities by Korea Mining Development Trading Corporation (KOMID) and

Green Pine Associated Corporation; possible activities of cash couriers; prohibited travel

by diplomats Kim Yong Chol and Jang Jong Son, KOMID President Kang Myong Chol, and

Green Pine Associated Corporation President Ri Hak Chol who are under travel ban.

Libya 14,5 mm heavy machine gun ammunition, attempts to establish military cooperation with

various Libyan authorities, involving designated entities including Green Pine Association,

Consulting Bureau for Marketing, a company belonging to a Hussein al-Ali;

Madagascar Sports stadium in Antananarivo; Iavoloha Palace, and other government installations.

Malaysia Glocom, DPRK owned distributor of military technology and missile navigation systems

and other arms-related products continuous operations out of Malaysia. Glocom is believed

to operate on behalf of Reconnaissance General Bureau of DPRK.

Assassination of Kim Jong Nam, half brother of Kim Jong Un, by North Korean agents, who

according to the Government of Malaysia used VX nerve agent.

Kay Marine Ltd, a company tied to DPRK, supplied boats to the Malaysian government.

Malaysia Korea Partners (MKP) Holdings established the International Consortium Bank in

Pyongyang, in violation of UN Sanctions in 2017.

Transshipment attempt in June 2009 of a magnetometer to Myanmar through Malaysia that

was interdicted by Japanese authorities.

Ocean Maritime Management operated an agency- office in Kuala Lumpur.

As of 2017, 300 North Korean laborers were working in Malaysia.

Bank of Eastland, a DPRK- controlled bank, was established in Malaysia that among others

also assisted Green Pine Associated.

Mali Bronze of General Abdoulaye Soumare

Mozambique Man-portable surface-air Pechora missile system; Training equipment; P-18 early- warning

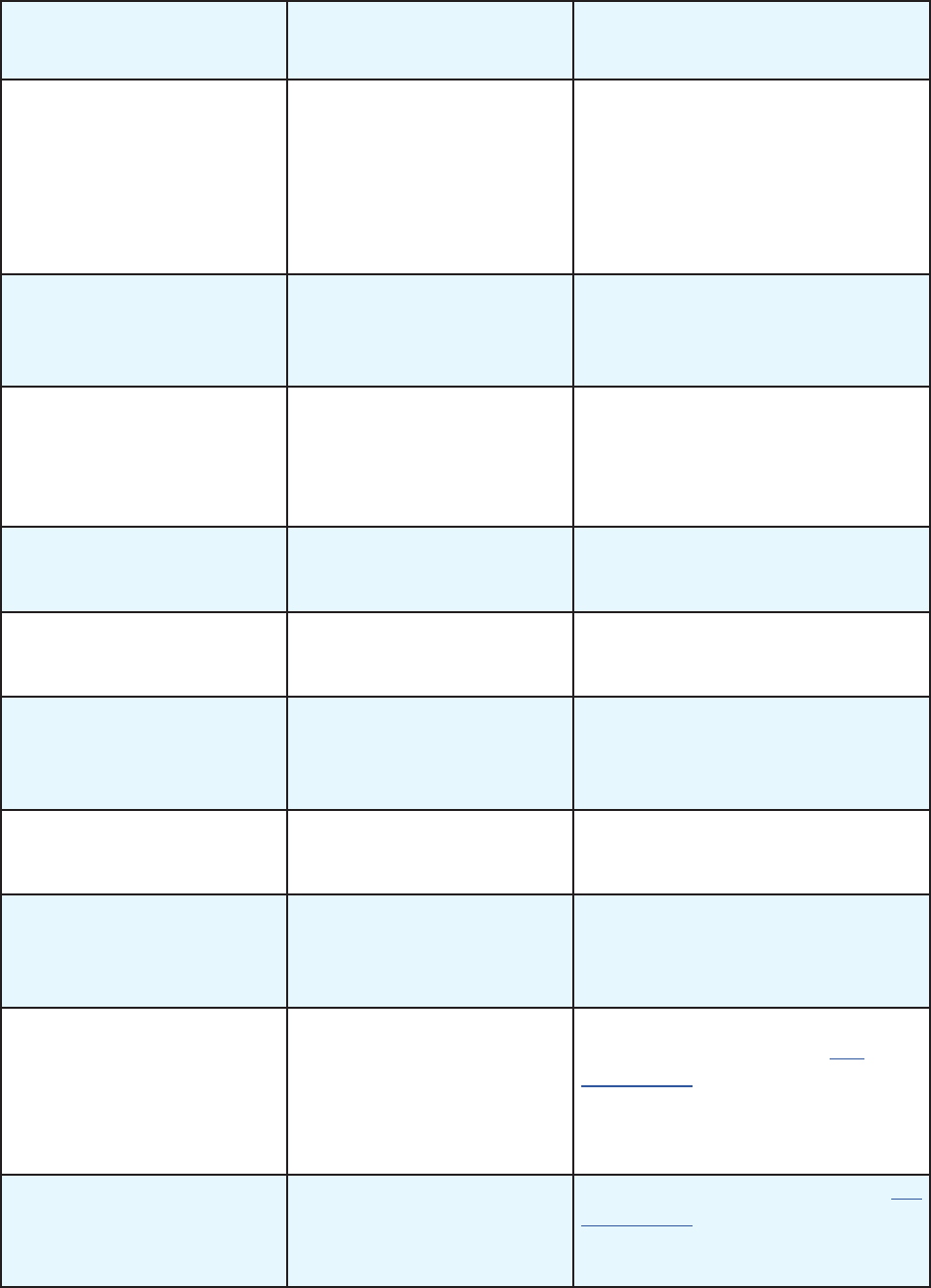

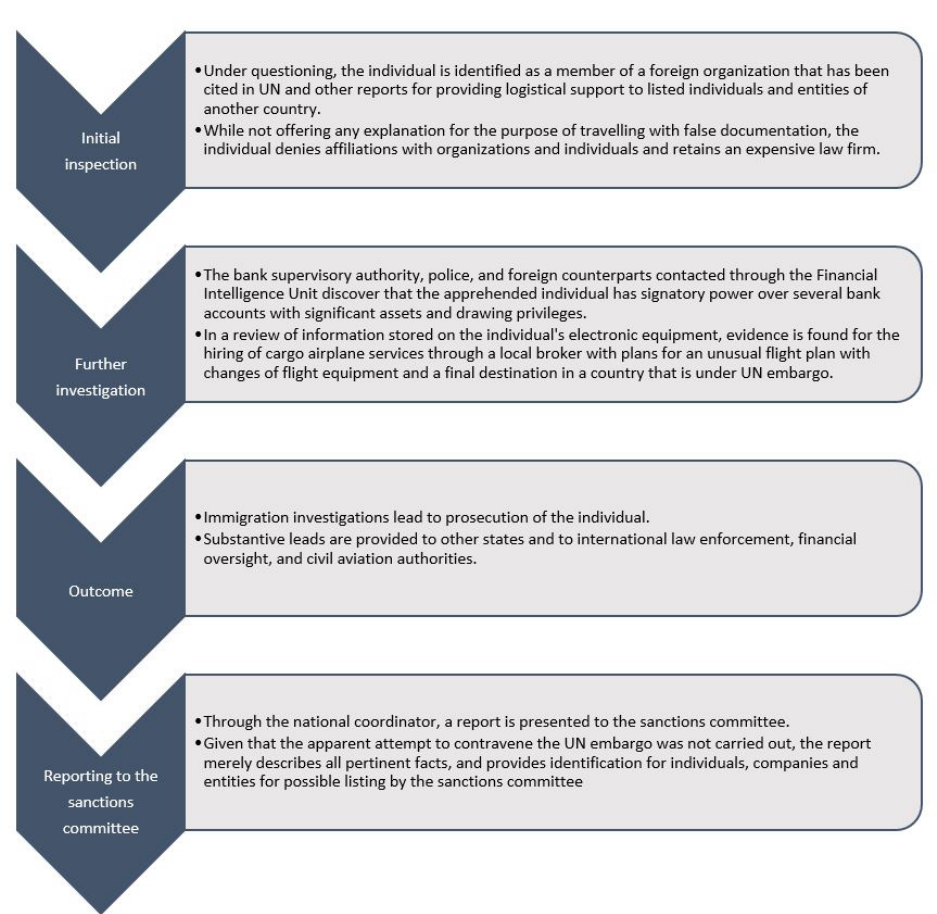

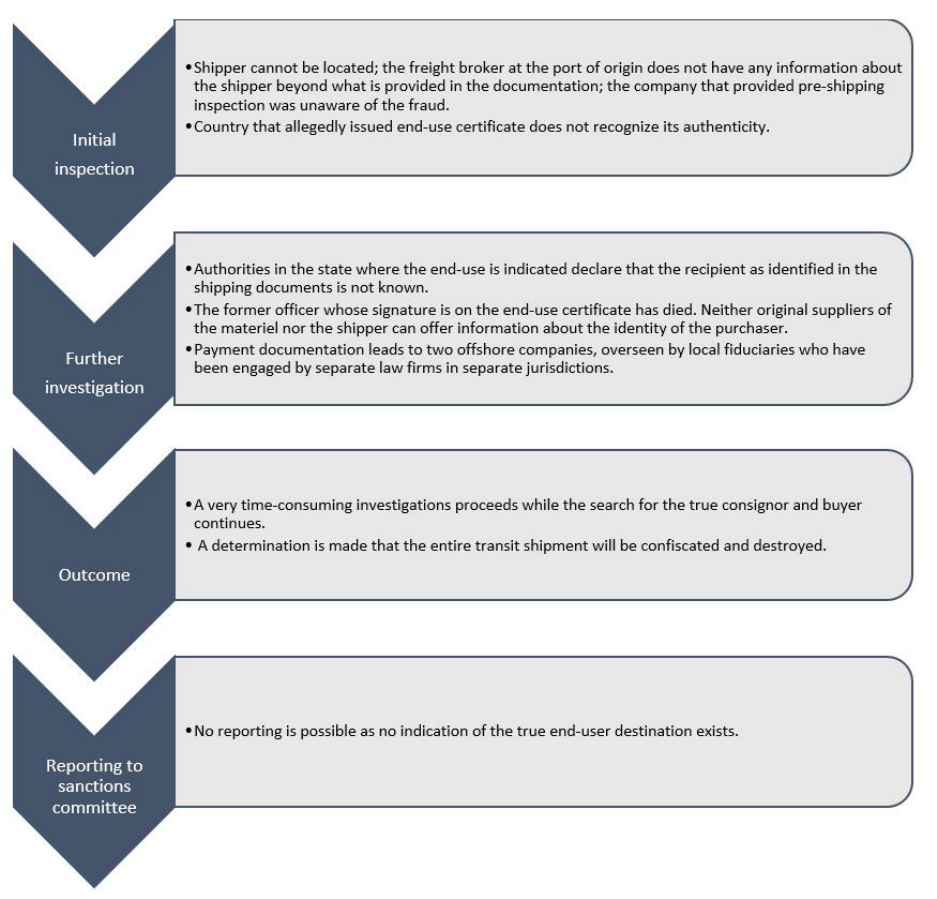

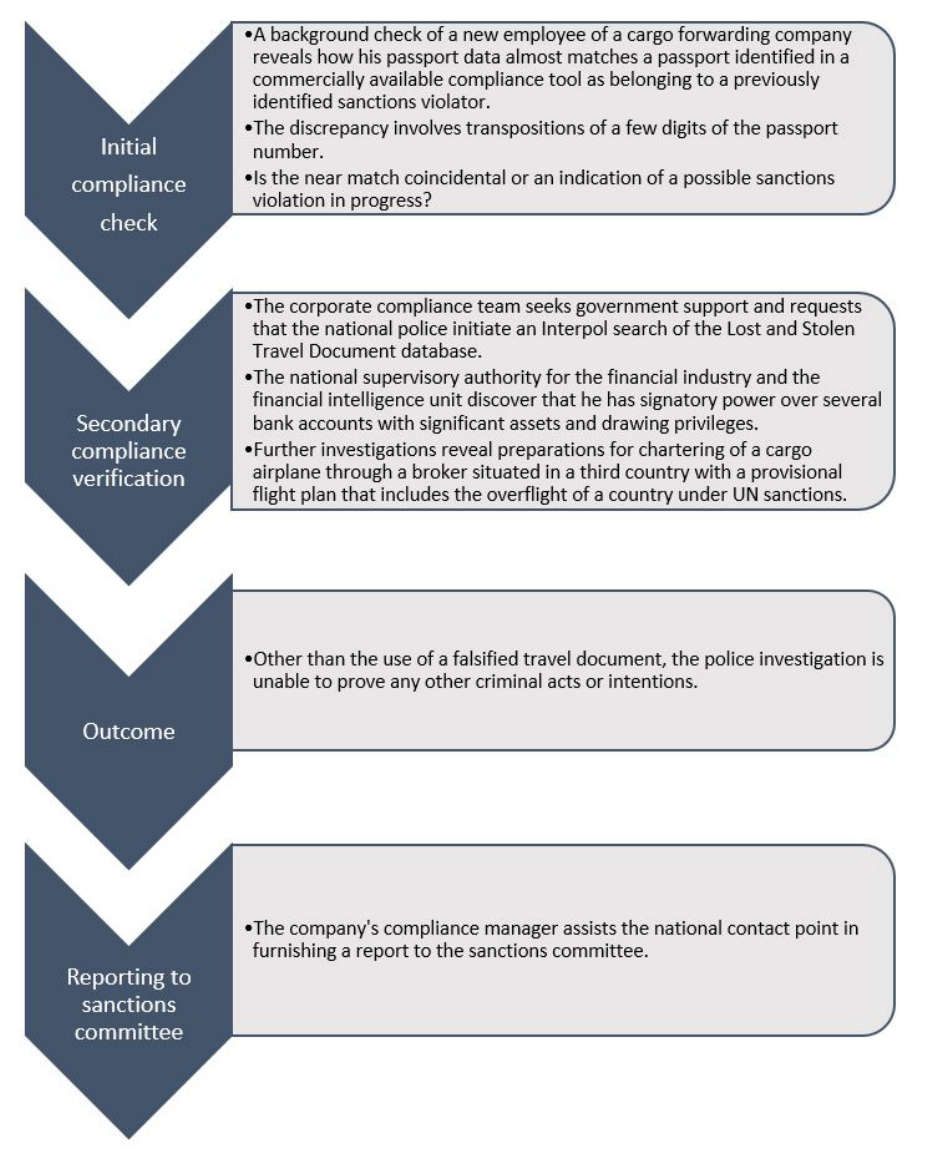

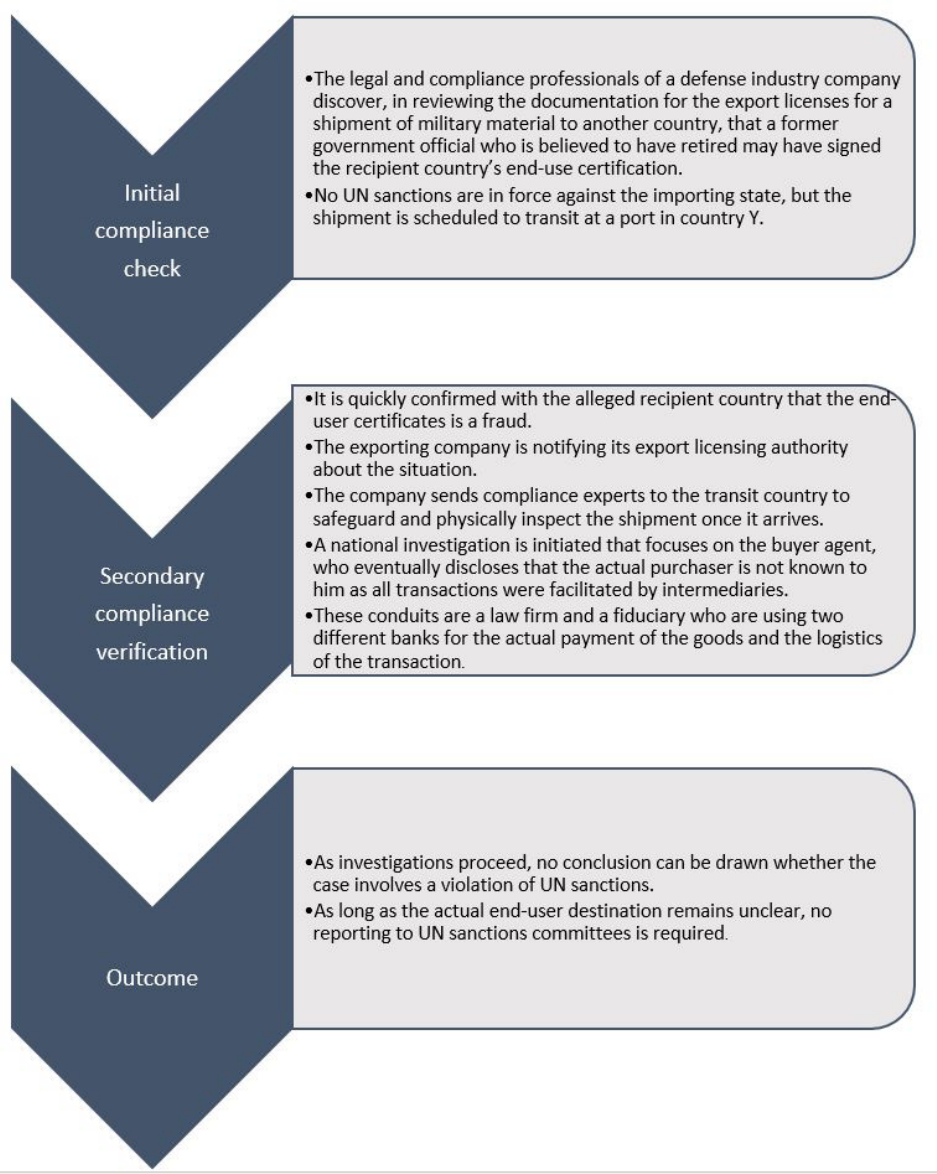

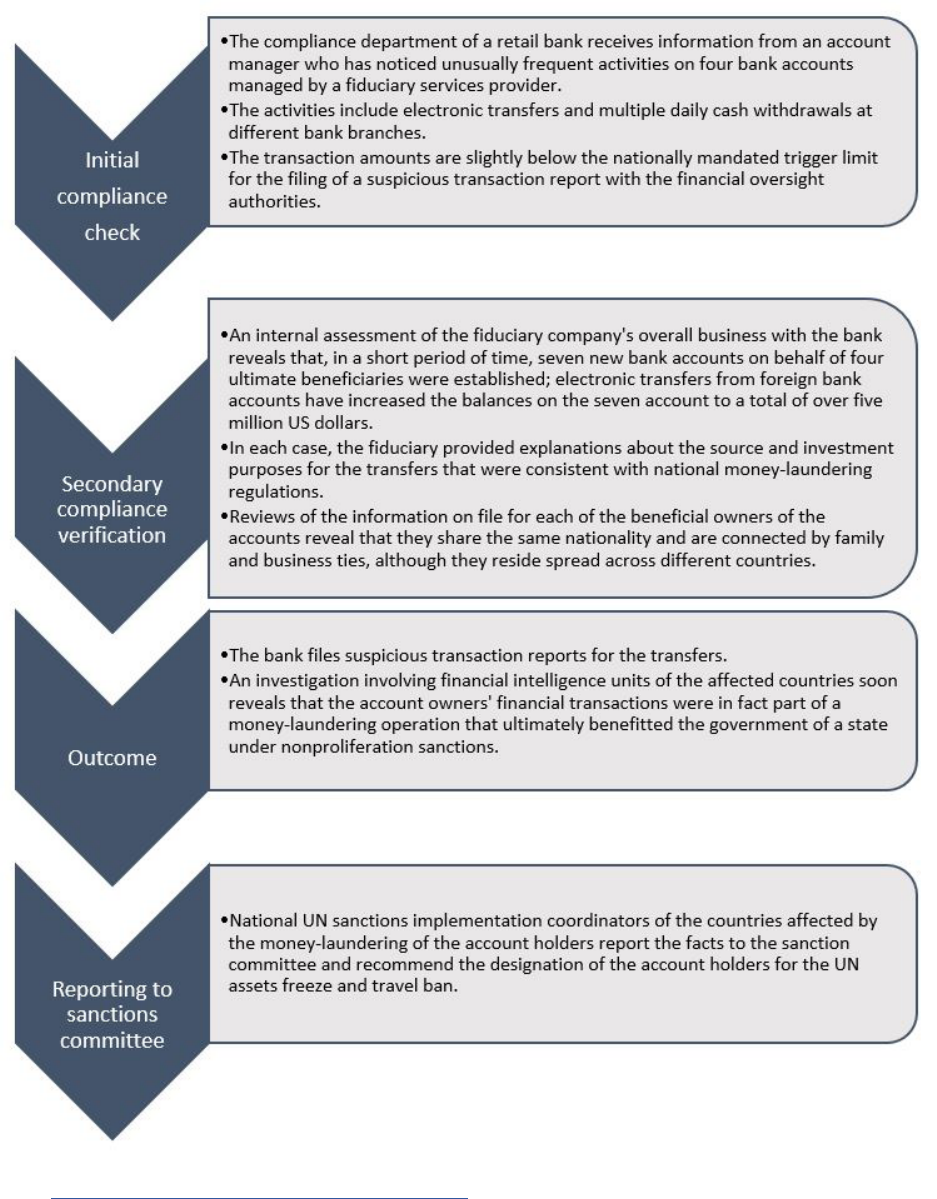

radar components; Empresa Moçambicana e Koreana de Investimento; Statue of the first