The Landscape

of Criminalization

1

GLOBAL ANALYSIS ON

CRIMES THAT

AFFECT THE

ENVIRONMENT

Crimes that Affect

the Environment

2 3 4 51 The Landscape of

Criminalization

2

© United Nations, May 2024

This publication may be reproduced in whole or in

part and in any form for educational or non-prot

purposes without the special permission from the

copyright holder, provided acknowledgement of the

source is made. The United Nations Ofce on Drugs

and Crime (UNODC) would appreciate receiving a

copy of any publication that uses this publication as

a source.

Suggested citation:

UNODC, Global Analysis on Crimes that Affect

the Environment – Part 1: the Landscape of

Criminalization (United Nations publication, 2024).

No use of this publication may be made for resale or

any other commercial purpose whatsoever without

prior permission in writing from UNODC. Applications

for such permission, with a statement of purpose and

intent of the reproduction, should be addressed to

the Research and Trend Analysis Branch of UNODC.

Comments on the report are welcome and can be

sentto:

Research and Trend Analysis Branch

United Nations Ofce on Drugs and Crime

PO Box 500

1400 Vienna

Austria

E-mail: unodcr[email protected]

Website: www.unodc.org/unodc/en/

DISCLAIMER

The designations employed and the presentation

of material in this publication do not imply the

expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of

the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the

legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or

of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its

frontiers or boundaries.

This publication has not been formally edited.

Crimes that Affect

the Environment

2 3 4 51 The Landscape of

Criminalization

3

The Global Analysis on Crimes that Affect the Environment:

Part 1

The Landscape of

Criminalization

May 2024

Crimes that Affect

the Environment

2 3 4 51 The Landscape of

Criminalization

4

Acknowledgements

The Global Analysis on Crimes that Affect the Envi-

ronment – Part 1: the Landscape of Criminalization was

prepared by Research and Trend Analysis Branch, Di-

vision for Policy Analysis and Public Affairs, United

Nations Ofce on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), under

the supervision of Jean-Luc Lemahieu, Director of the

Division, and Angela Me, Chief of the Research and

Trend Analysis Branch

Content overview

Anja Korenblik

Angela Me

Tanya Wyatt

Research, analysis and drafting

Erica Lyman

Tanya Wyatt

Research support

Ramy Abdelhady

Melissa Arango

Anneli Cers

Nick Fromherz

Marco Garcia

Ayman Irfan

Miranda Herried

Alison Hutchinson

Fabian Keske

Felix Knoebel

Antonia Langowski

Ted Leggett

Tanyaradzwa Muzenda

Angela Pascal

Giulia Serio

Mackenzie Springer

Louisa Zinke

Graphic design and production

Kristina Kuttnig

David Gerstl

Katja Zöhrer

Editing

Sarah Crozier

Programme, budget management

and support team

Andrada-Maria Filip

Harvir Kalirai

Iulia Lazar

Luka Zagar

Review and comments

Part 1: the Landscape of Criminalization beneted

from the expertise of and invaluable contributions

from within RAB and from UNODC colleagues in all

divisions.

The Research and Trend Analysis Branch acknowl-

edges the invaluable contributions and advice provid-

ed by members of the Global Analysis on Crimes that

Affect the Environment Technical Working Group:

Buba Bojang

Blaise Kuemlangan

Julia Nakamura

Nigel South

Daan van Uhm

Sallie Yang

The publication was made possible by the generous

nancial contributions of France and Germany.

Crimes that Affect

the Environment

2 3 4 51 The Landscape of

Criminalization

5

Content

Findings . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6

Conclusions and Policy Implications . . . . . . . . 10

Introduction. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .12

Regional agreements . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14

International conventions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14

Methodology . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18

The Analysis . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20

The state of criminalization . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20

Legal vs natural persons . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20

Other sanctions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20

Deforestation and logging . . . . . . . . . . . . . 22

Mining . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .23

Pollution . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 24

Air pollution. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .24

Noise pollution . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 25

Soil pollution . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 26

Water pollution. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 27

Fishing-related offences . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 28

Waste-related offences . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 29

Wildlife-related offences . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 30

Geographic Variations in Criminalization of Crimes

that Affect the Environment . . . . . . . . . . . . 32

Africa . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .33

Americas. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .33

Asia . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 33

Europe . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 33

Oceania . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 33

Conclusions and Policy Implications . . . . . . . 36

Regional Groupings . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 38

Endnotes. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 40

Crimes that Affect

the Environment

2 3 4 51 The Landscape of

Criminalization

6

Findings

Overall criminalization of activities that harm the

environment

•

No single international legal instrument compre-

hensively protects the environment, criminaliz-

es all behaviours that harm the environment, nor

denes crimes that affect the environment. The

legal protection of the environment is a complicat-

ed patchwork of international and regional agree-

ments ratied and transposed to varying degrees

into national legislative frameworks. Such complex

and unharmonized regulations create a landscape

where criminal and/or economic interests can take

advantage of loopholes and gaps in legislation and

its enforcement as well as a landscape conducive to

criminal inltration of legitimate sectors.

•

Today, many countries make use of the law and

criminal penalties to protect the environment,

although with some differences across environ-

mental areas. In most countries in the world, prison

sentences can be imposed for violating laws regu-

lating deforestation and logging, mining, air pollu-

tion, noise pollution, soil pollution, water pollution,

shing, waste, and wildlife. A high rate of criminal-

ization of harmful behaviours exists across these

nine environmental areas. Wildlife and waste are

the areas where most countries have at least one

related criminal offence in their national legisla-

tion. Soil and noise pollution are the areas where

the fewest countries have criminal provisions.

•

The level of protection afforded to the environment

is related to the conditions of each country. For ex-

ample, all the countries of Southern Africa regard of-

fences related to air pollution, deforestation and log-

ging, mining, waste and wildlife as criminal acts. In

contrast, no countries among the small island states

of Micronesia regard violations of deforestation and

logging legislation as a crime, perhaps because

commercial forestry is not an issue in the region.

Activities that harm the environment considered as

serious crime

•

At least 85% of United Nations Member States

criminalize offences against wildlife and at least

45% punish some of these offences with four

years or more in prison, which constitutes a serious

crime under the UN Convention Against Transna-

tional Organized Crime (UNTOC). For example, in

Eastern Africa, 12 out of 18 countries regard wild-

life offences as serious crimes, with the potential

for long prison sentences, while illegal shing is

considered most grave in Oceania, where 43% of

the countries regard it as a serious crime.

•

Waste offences are taken even more seriously,

with almost half of the countries regarding these

offences as serious crimes, including half the

African countries (perhaps due to the Bamako

Convention) and 62% of countries in Western

Europe. Waste offences is also an area where the

liability of legal persons (such as corporations) is

recognized in over three-quarters of countries.

• Africa and the Americas have the highest propor-

tions of countries with criminal offences related

to all nine environmental areas analysed, while

Africa and Asia have the highest average percent-

age of Member States with penalties meeting the

serious crime denition across the nine crimes (30

per cent respectively). Where there are no criminal

offences, countries typically use administrative of-

fences (see Figure 1).

•

The highest average percentage of Member

States with penalties meeting the serious crime

denition are in Africa and Asia, indicating not that

legislation there may be ‘weak’, as is commonly

stated, but that there is a lack of enforcement of

the legislation.

Crimes that Affect

the Environment

2 3 4 51 The Landscape of

Criminalization

7

The role of international conventions

The two environmental areas with the highest levels

of criminalization – waste and wildlife – are, at least

in part, governed by international conventions – the

Basel Convention on the Control of Transboundary

Movements of Hazardous Wastes and their Disposal

and the Convention on International Trade in Endan-

gered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) re-

spectively. Both conventions have been widely ratied

by UN Member States (188 and 183 respectively – see

Figure2). The requirement of the Basel Convention

to criminalize violations of its provisions explains the

high level of the criminalization of waste violations (of

160 Member States that criminalize, 157 are parties

to the Basel Convention). In terms of wildlife, CITES

does not specically require criminalization. The high

level of criminalization of wildlife violations is likely

a combination of decades of campaigning related to

wildlife protection, CITES having existed for 50 years

(nearly twice as long as the Basel Convention), and

CITES’ National Legislation Project that evaluates im-

plementation of the convention.

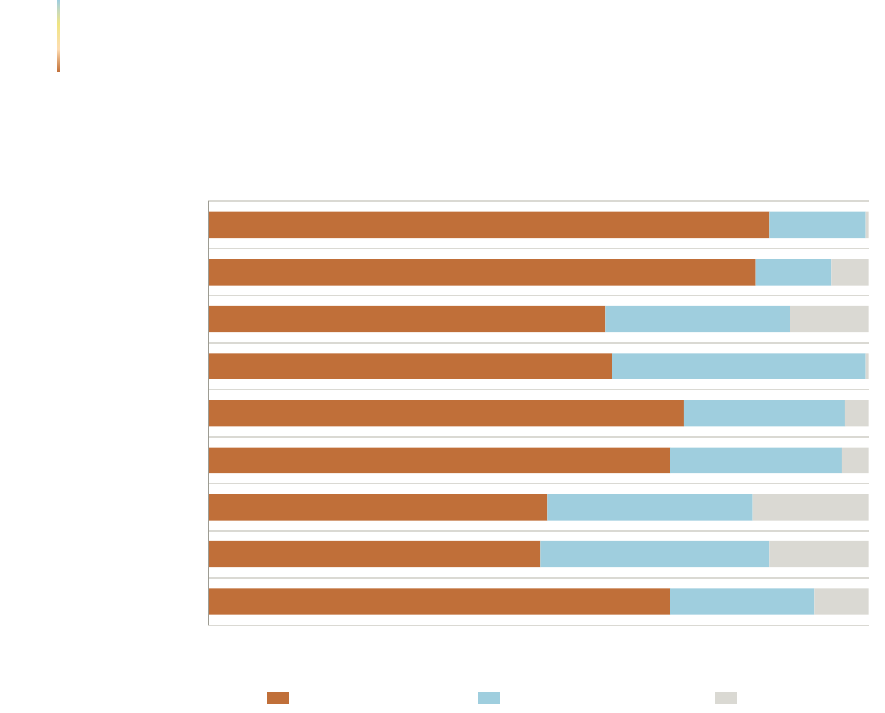

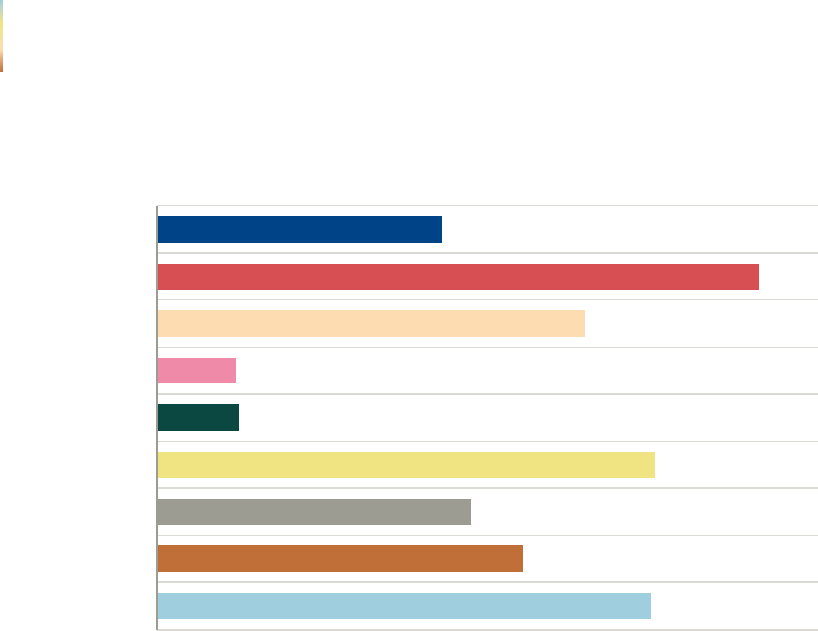

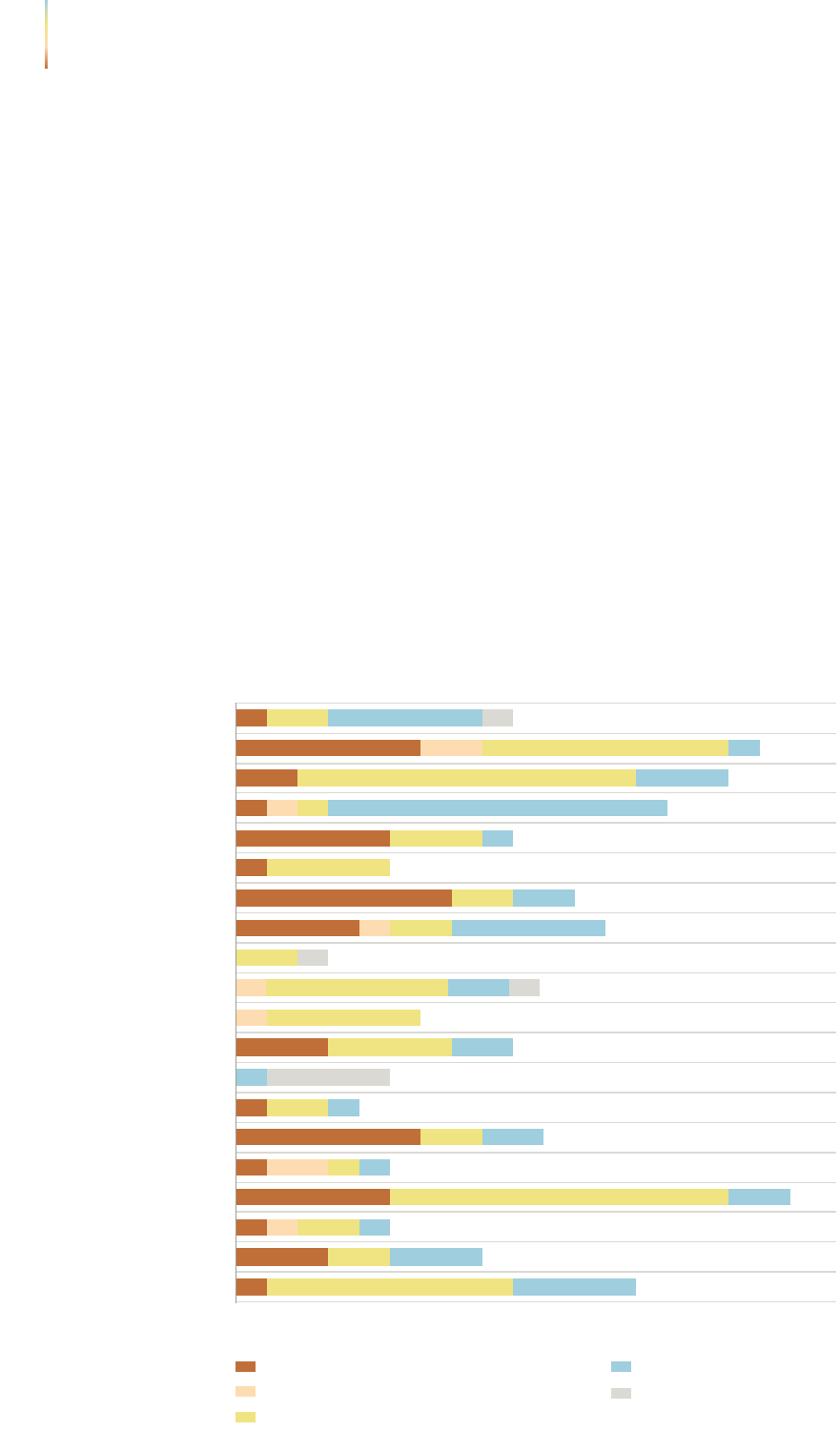

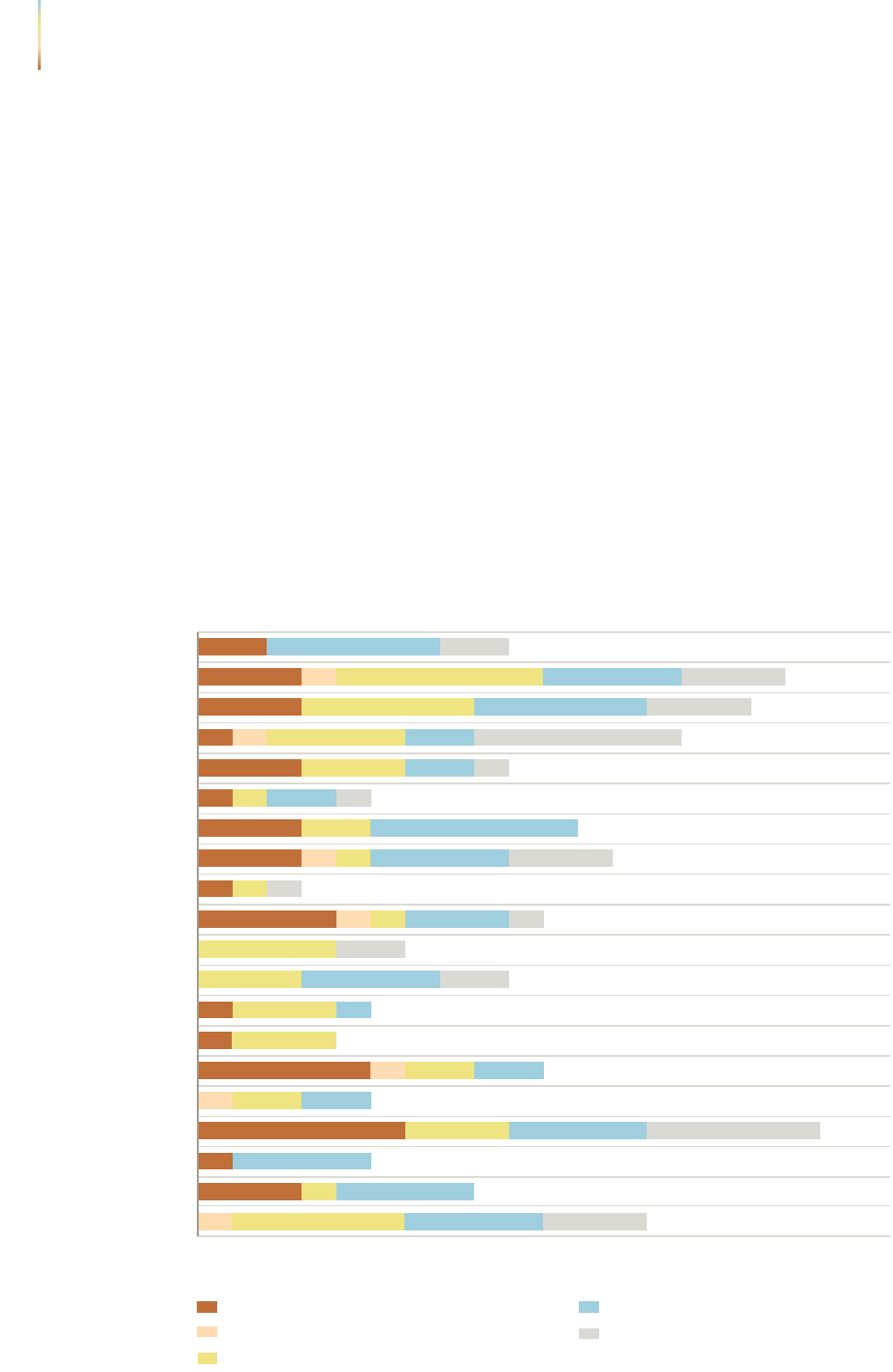

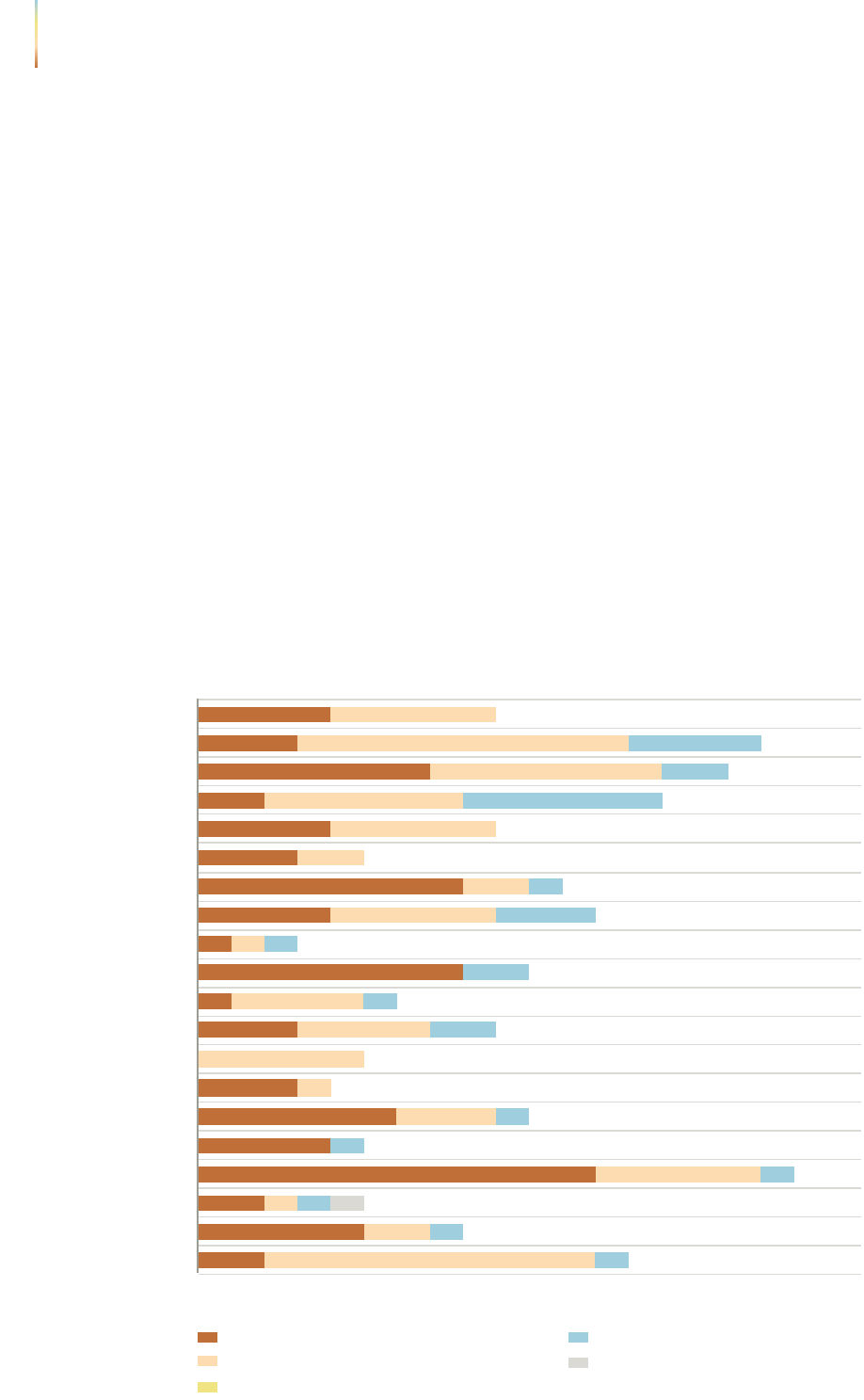

Figure 1 – State of criminalization (Number of UN Member States)

Air pollution

Noise pollution

Soil pollution

Water pollution

Deforestation

and logging

Fishing

Mining

Waste

Wildlife

Environmental area

Number of Member States

135

97

99

135

139

118

116

160

164

42

67

60

50

47

74

54

22

28

16

29

34

8

7

1

23

11

1

Criminal penalties No criminal penalties No data

Crimes that Affect

the Environment

2 3 4 51 The Landscape of

Criminalization

8

Ecocide

•

Some countries dene ecocide as a crime (see

Rights of Nature and Ecocide). The crime of eco-

cide cannot replace the consideration for crim-

inalization of harms that affect the environment,

but instead it may be a helpful complement in the

most egregious or systemic cases.

Known Liability of Legal Persons

• Liability of legal persons is an important aspect to

crimes that affect the environment as often legal

persons such as corporations are the offenders.

Violations of air pollution (120 Member States) and

waste regulations (146 Member States) are the

most likely types of offences for which liability of

legal persons is expressly established in the envi-

ronmental legislation.

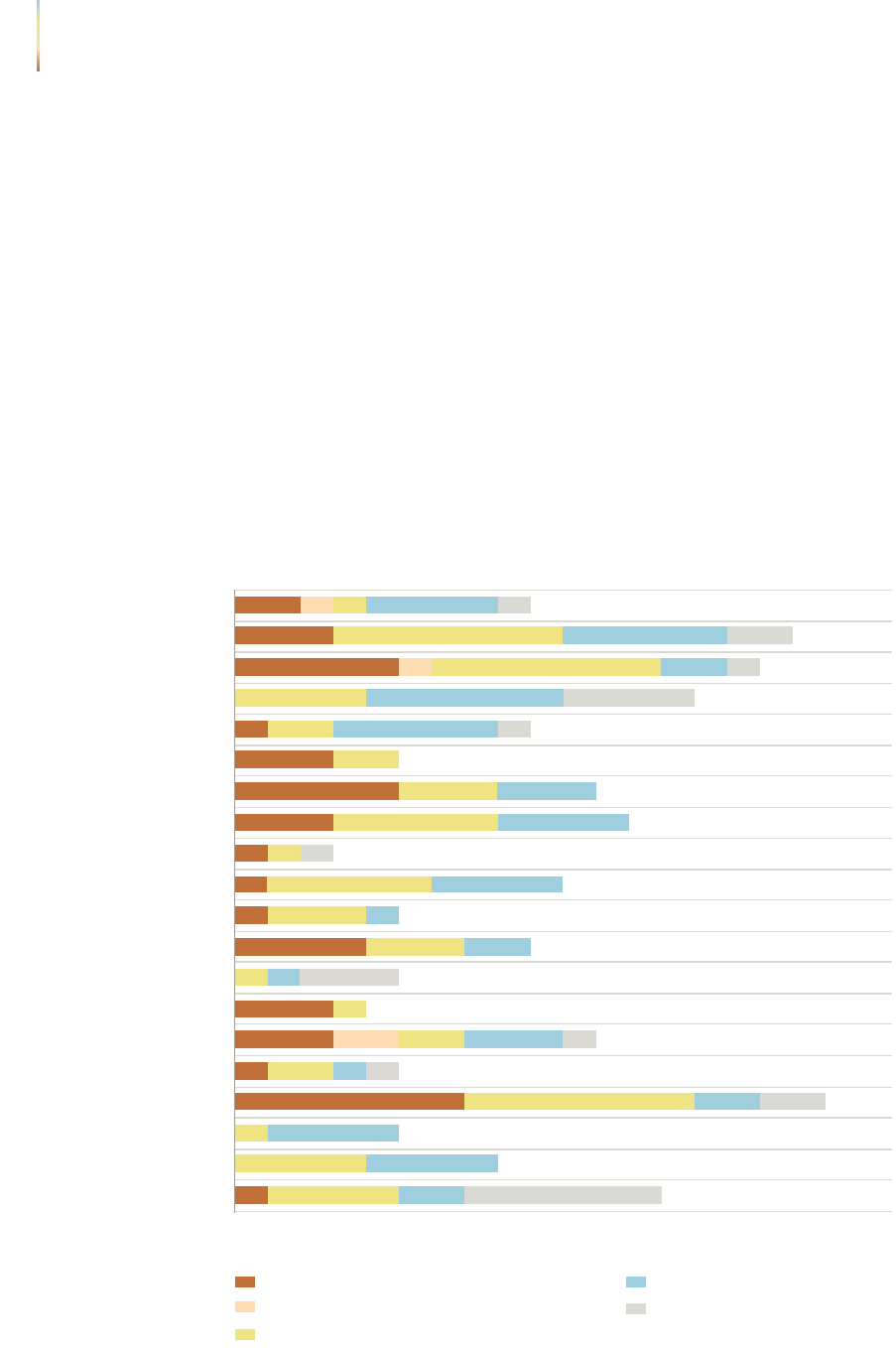

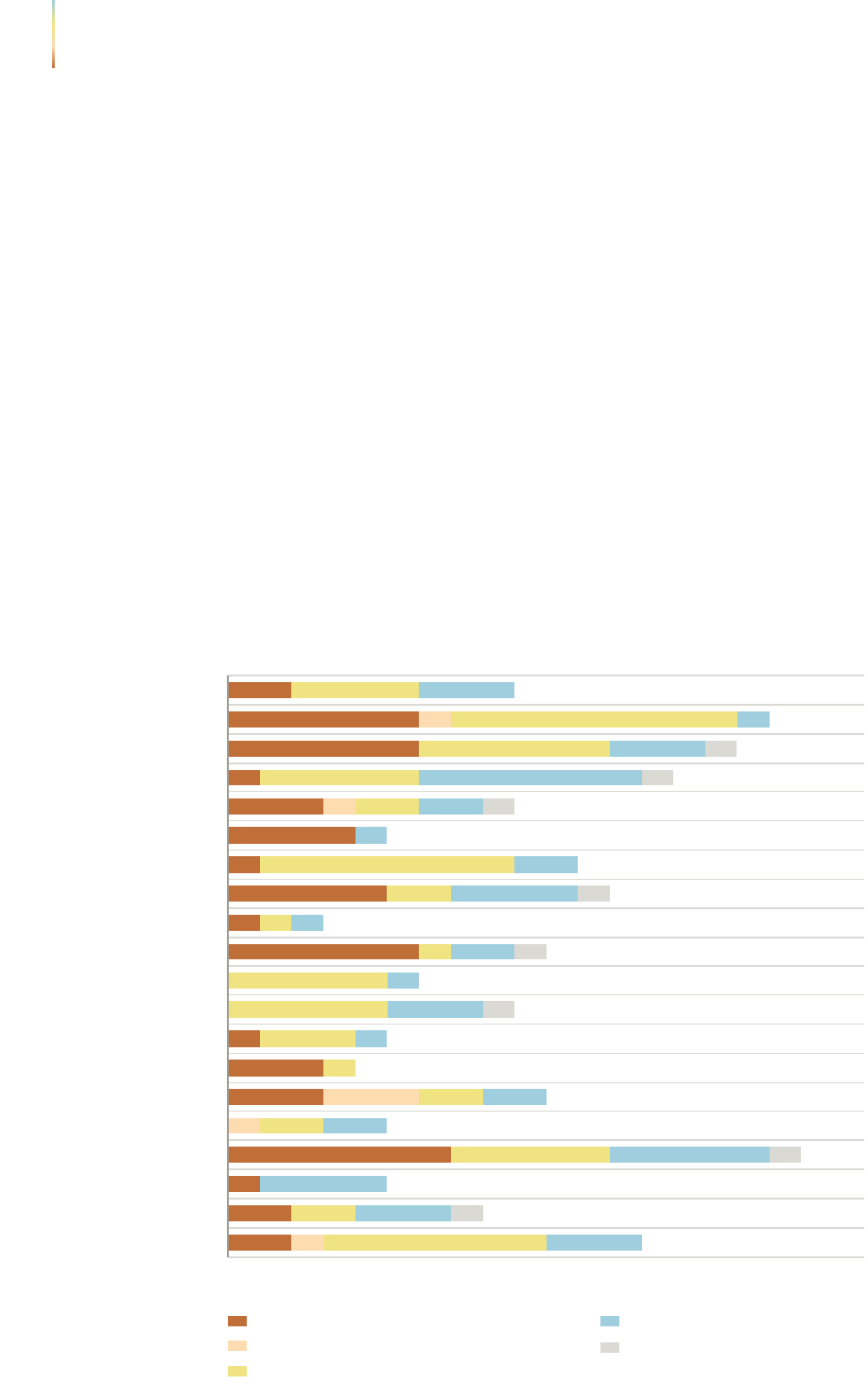

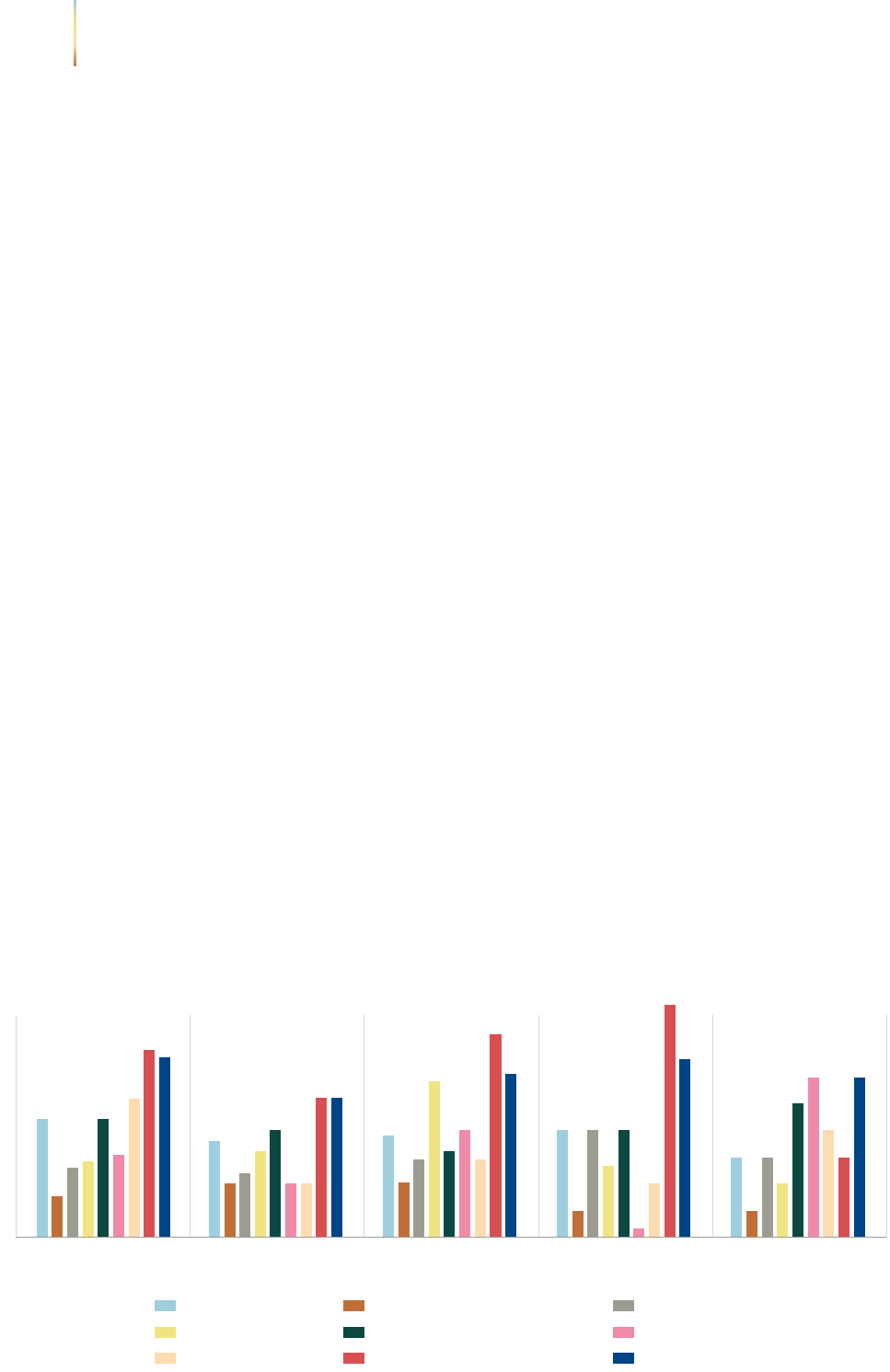

54

22

41

55

49

45

95

86

11

9

7

7

9

4

10

70

66

51

73

81

67

55

78

42

67

60

50

47

54

22

28

16

29

34

8

7

34 10 74 74

1

23

11

1

Criminal penalty is a serious crime

Criminal penalty is unknown

Criminal penalty is not a serious crime

No criminal penalty

No data

Number of Member States

Air pollution

Noise pollution

Soil pollution

Water pollution

Deforestation

and logging

Fishing

Mining

Waste

Wildlife

Environmental area

155

28

157

21

10

Basel

Convention

CITES

Criminalized Not criminalized Unknown

The State of criminalzation of violations of the Basel

Convention and CITES for United Nations Member

States which are parties to these conventions

Figure 3 – Member States with legislation meeting the UNTOC denition of serious crime of

at least four years in prison

Figure 2 – State of criminalization of the parties to

the Basel Convention and CITES by UN Member

States

Crimes that Affect

the Environment

2 3 4 51 The Landscape of

Criminalization

9

Repeat Offences

•

Relatively few Member States appear to address

either recidivism or ongoing violations directly in

their environmental legislation.

Conscationof instrumentalities and proceeds of

crimes

•

Overall, conscation provisions for activities that

harm the environment do not appear common in

environmental legislation; for example, of the leg-

islation reviewed for this analysis only 37 coun-

tries provide for conscation regarding water-

related offences, despite 135 criminalizing water

pollution. Other legislation, including criminal leg-

islation, may cover such situations.

•

Further, conscation provisions more common-

ly appear to apply to equipment or objects (e.g.,

vehicles or wildlife products) related to the crime

rather than prots or proceeds, particularly but

not exclusively with respect to pollution crimes.

Compensation, restoration, and restitution

•

While provisions exist providing for restorative

injunctive relief (compensation for environmen-

tal damage or funds to restore the environment),

these provisions are less common than the crimi-

nalization of offences.

Crimes that Affect

the Environment

2 3 4 51 The Landscape of

Criminalization

10

Conclusions and Policy

Implications

This review of environmental legislation shows that

countries have in place, to varying degrees, legal

frameworks that criminalize activities that harm the

environment. However, some environmental areas

and geographical areas are less covered than others

by criminal provisions, suggesting that some coun-

tries may perceive certain environmental areas less

in need of protection, less exposed to harmful prac-

tices or more difcult for protections to be enforced.

Establishing criminal or administrative offences is the

rst step to enforcing environmental protection, but

their effectiveness depends on a number of factors,

including the capacity of the criminal justice system

to implement them. So, despite the progress made in

environmental protection laws, there are a number of

priorities to consider to strengthen national legislative

frameworks to protect the environment:

•

Criminal penalties for crimes that affect the en-

vironment, regardless of their nature and harm,

remain low in many countries, below the thresh-

old of serious crime. Not all crimes that affect the

environment are of a serious nature and low-lev-

el offences require proportional criminal justice

responses. But for the most harmful offences,

penalties could be increased to meet the UNTOC

denition of serious crime across all nine environ-

mental areas analysed to enable Member States

to utilize the UNTOC provisions for international

cooperation (e.g., extradition, mutual legal assis-

tance). Further examination of criminalization and

penalties within (sub)regions is warranted to iden-

tify harmonization as well as potential loopholes

where countries with the least stringent legisla-

tion and penalties may be targeted by offenders.

1

2

3

•

While international conventions seem to have an

impact on the level of criminalization of wildlife

and waste offences, even more improvements

could be made in the context of the Basel Conven-

tion and CITES. For the Basel Convention, this is

particularly the case in Latin America where 10 UN

Member States do not criminalize waste offences

and for CITES this is the case for Southern Europe

and Western Asia where six and four UN Member

States respectively do not criminalize wildlife of-

fences.

• Very few countries have laws allowing for cons-

cation of the instrumentalities or the proceeds of

environmental offences. These deciencies may

lead to the prosecution of minor offenders, rather

than the large economic interests that often drive

crimes that affect the environment. So, strength-

ening environmental legislation to cover seizure

and conscation of assets related to crimes that

affect the environment is another area that needs

urgent attention.

•

Liability for legal persons is another area for im-

provement. Only 19 countries have known liability

for legal persons regarding shing-related offenc-

es and 20 for deforestation and logging-related

offences, two environmental areas in which cor-

porate malfeasance is common. This may indicate

that economic interests may be blocking efforts to

better protect the environment.

•

Certain geographical areas could be prioritized for

improving legal frameworks to protect the envi-

ronment. For example, Central Asia for pollution

and mining-related offences and Europe for sh-

ing-related offences. Only 20 per cent of Central

Crimes that Affect

the Environment

2 3 4 51 The Landscape of

Criminalization

11

Asian countries have provisions that criminalize

pollution (noise, soil, water) and mining offences,

despite being a region strongly affected by these

crimes. And only 2 per cent of European countries

regard shing-related offences as a serious crime.

•

While the analysis has revealed progress and chal-

lenges on how environmental law deals with the

criminalization of activities that harm the environ-

ment, knowledge gaps remain. Additional analy-

sis is needed on how corruption in these environ-

mental areas is treated and penalized. Despite

the level of criminalization, there is a lack of data

on arrests, prosecution convictions, and custodi-

al sentencing,

4

which calls for capacity-building

in terms of data collection on crimes that affect

the environment as well as on implementation and

enforcement of existing legislation. Also, further

research is needed into the enforcement of these

legislation and the range of criminal penalties

administered, and importantly, what the effects

are of these sanctions. It is critical to understand

which combinations of criminalization and restor-

ative approaches are most effective at preventing

crimes that affect the environment.

Crimes that Affect

the Environment

2 3 4 51 The Landscape of

Criminalization

12

Introduction

The Earth is facing a triple planetary crisis – climate

change, biodiversity loss, and pollution. One aspect of

combating this crisis is protecting the planet through

the criminalization of acts that harm the environment.

Some international organizations and studies have

called for legislative frameworks to be improved and

for crimes that affect the environment to be dened

as serious and/or organized crimes.

5

6

United Nations

General Assembly Resolution A/RES/76/185 also

“calls upon Member States to make crimes that affect

the environment, where appropriate, serious crimes”.

7

Criminalization can be an important symbol that cer-

tain actions are prohibited. Having higher penalties

for crimes can not only dissuade potential and repeat

offenders,

8

9

it can also broaden the range of investi-

gative tools and resources for law enforcement.

10

In

particular, if the offence is punishable by a maximum

deprivation of liberty of at least four years or a more

serious penalty, this enables parties to the UN Conven-

tion against Transnational Organized Crime (UNTOC)

to apply extradition and mutual legal assistance.

11

The extent of criminalization of harmful acts to the

environment is unknown. This rst publication of the

Global Analysis on Crimes that Affect the Environment

helps to ll these gaps in knowledge by answering the

following research questions: To what extent does the

environmental legislation of the 193 Member States

of the United Nations criminalize actions that harm

the environment? How are any such criminal offences

penalized, and does this conform to the denition of

serious crime set out in the UNTOC?

According to a 2022 background note from the Com-

mission on Crime Prevention and Criminal Justice

(CCPCJ), “Data on environmental crimes are collect-

ed only when a clear and separate denition of the

legal offence exists in national criminal law. In many

countries, for instance, actions that have a signicant

negative impact on the environment fall primarily un-

der administrative offences or environmental or health

regulations and are therefore not reected in crime

statistics”.

12

As noted in the above statement, harm to the envi-

ronment is not always considered a criminal offence.

An important, substantive distinction exists between

criminal legislation generally and environmental leg-

islation. Namely, environmental legislation is viewed

as establishing the standards of behaviour and proce-

dure for regulatory agencies and for legal and natural

persons engaging in activities that in some way affect

the environment. Typically, this includes provisions on

how to obtain permits, reporting obligations, prohibi-

tions and restrictions, and other regulatory provisions.

Often, but not always, such legislation will make vio-

lations of the standards an offence. Sometimes these

offences are treated as criminal offences and han-

dled, when they occur, through the criminal justice

system by state or local prosecutors; other times,

the offences may be civil offences, creating causes

of action that may be brought by the government or

by citizens in the public interest. And sometimes of-

fences may be treated administratively – typically, this

means that the regulatory agency imposes a ne or

some other type of penalty that does not involve the

criminal justice system.

In contrast, a penal code or other criminal legislation

or common law establishes those actions that are

treated as criminal offences and that are prosecutable

through the criminal justice system. Criminal legisla-

tion that could be relevant to the environment includes

money laundering legislation, legislation that crimi-

nalizes corruption, and general criminal codes, for ex-

ample. This legislation is not “environmental”, just like

environmental legislation is not “criminal” even though

they intersect. This analysis looks at “environmental”

legislation and asks whether such legislation includes

criminal offences. It is not a comprehensive analysis of

Crimes that Affect

the Environment

2 3 4 51 The Landscape of

Criminalization

13

criminal laws that might include environment-related

offences.

In relation to environmental legislation, a complex

interplay exists between international agreements,

regional environmental agreements, national leg-

islation, and even sub-national legislation (state- or

provincial level legislation in Member States that are

federated). Thus, to understand when an act is a crime

that affects the environment, it is essential to exam-

ine this interplay. Regional and international treaties

are voluntary instruments, but when a party raties

an international agreement, the party is obliged to

implement and enforce the terms of the agreement,

which means, in many cases, ensuring that national

legislation complies with obligations under the agree-

ment.

13

Several regional and numerous international

conventions have provisions relevant to crimes that af-

fect the environment, and some may ask parties to the

agreements to establish as criminal offences certain

acts that harm the environment.

14

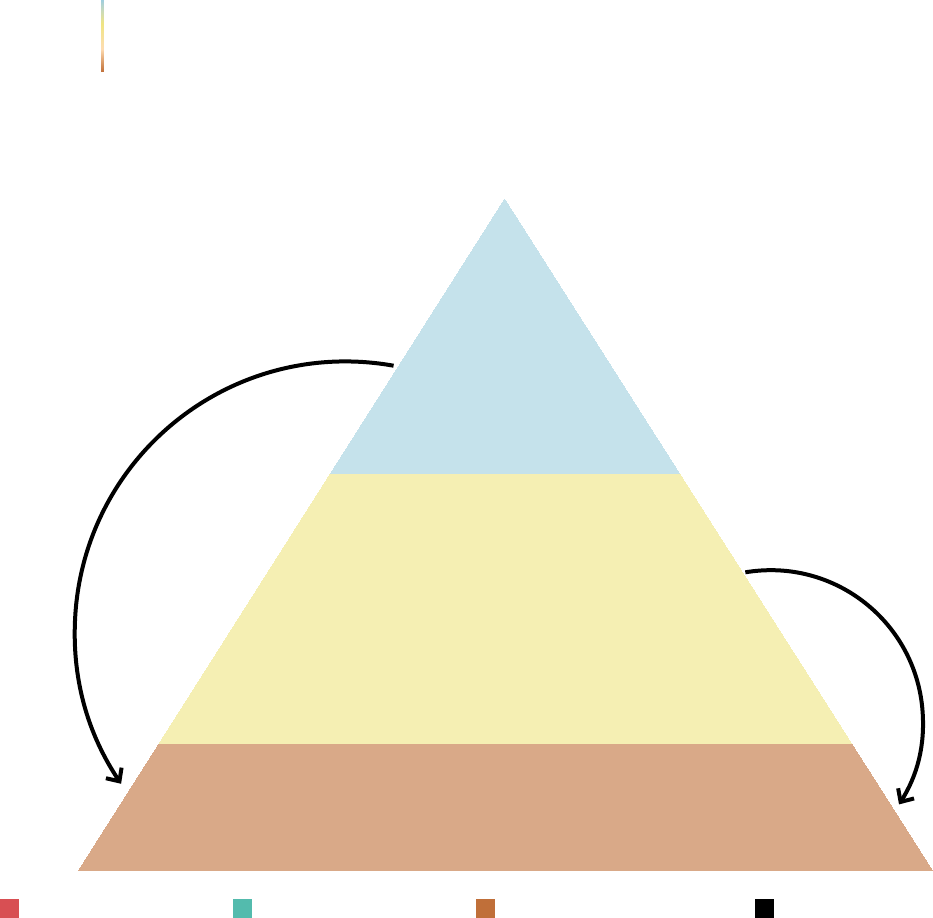

Figure 4 illustrates

the legal instruments at the different levels of gov-

ernance – there are fewer regional agreements, more

international conventions, and thousands of national

laws. Figure 4 also illustrates how national laws can

be linked to the provisions of regional agreements

and international conventions. These are color coded

to show which regional agreements and international

conventions are specic to climate change, biodiver-

sity loss, pollution and waste, and the environment in

general. These codes are somewhat oversimplied as

there is not a clear distinction between these differ-

ent areas and for example many forms of biodiversi-

ty loss and pollution and waste impact upon climate

change and vice versa. Some of the most important

of the regional agreements and international conven-

tions are discussed below before an analysis of the

state of criminalization for offences related to each of

the nine environmental areas analysed (deforestation

and logging, mining, air, noise, soil and water pollution,

shing, waste, and wildlife). An analysis of the geo-

graphic variations of criminalization follows.

Box 1 – RIGHTS OF NATURE AND ECOCIDE

Criminalizing certain acts that harm the environment

is only one approach to protect the environment. Na-

tional legislation may embed other ways to protect

the environment. Just two examples (which may or

may not incorporate some criminal law elements) are

Rights of Nature and ecocide.

Rights of Nature

Rights of Nature is an approach that recognizes that

nature, in whole or in part, has inherent rights to exist,

thrive, and regenerate. Using this approach, some le-

gal systems have enforcement provisions that protect

those rights, such as by allowing cases to be brought

on behalf of an ecosystem, an element of a particu-

lar landscape, a species, or even an individual animal

when there is or is likely to be harm. Under the Rights

of Nature approach, human behaviour may be subject

to regulation to avoid harm to the environment or pro-

vide redress to compensate for such harm. Courts are

typically the arbiters of claims that are put forward on

behalf of nature, and injunctive relief may come in the

form of remanding government decision-making, halt-

ing development projects, pollution control measures,

or other protective or procedural orders.

15

Among the several examples of Rights of Nature court

cases, the Atrato River Decision in Colombia is instruc-

tive as an example of how such cases have the po-

tential to engage Indigenous Peoples and Local Com-

munities (IPLCs), protect the environment through law

and policy, and restore damaged ecosystems. In this

case, an organization brought a case to Colombia’s

Constitutional Court, and the court subsequently held

that the Atrato River had legal personhood deserving

of protection under the law as recognized by the Co-

lombian Constitution. In its ruling, the Court, among

other steps, ordered the development of a joint plan to

halt illegal gold mining, including the seizure of any in-

strumentalities of such mining, the prosecution of any

organizations or persons participating in illegal min-

ing, and a plan to decontaminate the river and restore

the ecosystem.

16

17

The rationale behind the ruling was

“La tierra no le pertenece al hombre sino, por el con-

trario, es el hombre quien pertenece a la tierra” – “The

earth does not belong to man [any person], but rather,

it is man [any person] who belongs to the earth.”

18

Crimes that Affect

the Environment

2 3 4 51 The Landscape of

Criminalization

14

Ecocide

According to an independent, expert panel, ”ecocide”

is the “unlawful or wanton acts committed with know-

ledge that there is a substantial likelihood of severe

and either widespread or long-term damage to the en-

vironment being caused by those acts.”

19

The devel-

opment of this denition exists as part of an ongoing

campaign to have ecocide adopted as an international

crime via the Rome Statute of the International Crim-

inal Court. As it currently stands, “long-term and se-

vere damage to the environment” constitutes a crime

prosecutable at the International Criminal Court via

the Rome Statute only when it occurs during war-

time.

20

According to one source, some nations have

begun to adopt legislative provisions that criminalize

acts that may be categorized as ecocide.

21

While adopting ecocide laws may help to reduce en-

vironmental harm, the denitional thresholds may be

a barrier to prosecution when the crime of ecocide

requires proving wanton or knowing mental states or

the known likelihood of signicant harm to the envi-

ronment.

Regional agreements

Regional agreements, also referred to as treaties, are

relevant to an analysis of criminalization of environ-

mental degradation as they may ask Member States

to have legislation that criminalizes the violations of

certain treaty provisions. Two examples of this are the

Bamako and Waigani Conventions, though there are

many other relevant regional agreements. The Bama-

ko Convention, ofcially known as the Convention on

the Ban of the Import into Africa and the Control of

Transboundary Movement and Management of Haz-

ardous Wastes within Africa, was established in 1991

under the African Union.

The aim of the Convention is

to prohibit the import of all hazardous and radioactive

waste into Africa,

22

and the dumping or incineration

of hazardous waste in oceans and inland waters, while

promoting environmentally sound disposal.

23

Among

other obligations, parties to the convention are asked

to make unauthorized imports illegal and “to introduce

appropriate national legislation for imposing criminal

penalties on all persons who have planned, carried

out, or assisted in such illegal imports”.

24

The Waigani Convention, ofcially known as the Con-

vention to Ban the Importation into Forum Island

Countries of Hazardous and Radioactive Wastes and

to Control the Transboundary Movement and Man-

agement of Hazardous Wastes within the South Pa-

cic Region, was adopted in 1995. Like the Bamako

Convention, it states that prohibited imports shall be

deemed an illegal and criminal act in domestic leg-

islation.

25

This convention entered into force in 2001

and is structured after the Basel Convention, serving

as the South Pacic regional implementation of the

international hazardous waste control system.

26

International conventions

In relation to criminalization, of the numerous interna-

tional conventions that aim at protecting the environ-

ment, only the Basel Convention includes a specic

requirement to criminalize prohibited conduct under

parties’ domestic legislation.

27

28

In all the other con-

ventions, parties may choose to criminalize prohibit-

ed conduct, but no such explicit requirements exist.

For example, the Convention on International Trade of

Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES)

Article VIII explicitly requires parties to prohibit and

penalize violations of trade in specimens in violation

of the Convention, but it does not specically ask Par-

ties to criminalize these violations.

29

This means that

parties can be compliant in implementing the provi-

sions of the convention by employing administrative

penalties to address wildlife offences. Other multilat-

eral environmental agreements contain text to take

‘necessary measures,’ as opposed to requiring crim-

inalization. For instance, Article 15 of the Rotterdam

Convention on the Prior Informed Consent Procedure

for Certain Hazardous Chemicals and Pesticides in In-

ternational Trade provides the following:

“Each Party shall take such measures as may be

necessary to establish and strengthen its national

infrastructures and institutions for the effective

implementation of this Convention. These mea-

sures may include, as required, the adoption or

amendment of national legislative or administra-

tive measures…”.

30

Crimes that Affect

the Environment

2 3 4 51 The Landscape of

Criminalization

15

In addition to the national legislation that countries

have introduced in compliance with international con-

ventions, there are a series of other national laws that

have been introduced. Thus, to understand the state

of criminalization of acts that harm the environment, it

is necessary to look beyond regional agreements and

international conventions and analyse each Member

States’ legislation.

Box 2 – WORKING DEFINITIONS USED FOR THIS

ANALYSIS

To undertake the analysis of all 193 Member States’

legislation for the nine environmental areas, an

agreed-upon set of working denitions was adopted.

These working denitions were taken from United

Nations’ entities with a mandate in the environmen-

tal areas – the UN Environment Programme (UNEP)

for pollution and the Food and Agricultural Organiza-

tion (FAO) for illegal shing. The series of legislative

guides produced by UNODC were also a source for

these working denitions as the legislative guides

are grounded in the relevant international conven-

tions. For cross-cutting analysis of conscation, lia-

bility of legal persons, and serious crime, the UNTOC

supplied the working denitions. For environmental

areas where there was no UNODC legislative guide or

convention that covers all the relevant offences (ille-

gal deforestation and logging, and wildlife crime), the

working denitions were adapted from other similar

crime types where a denition already existed.

Conscation here refers to both the seizure and for-

feiture of the proceeds of crime (though these are

distinct concepts under UNTOC Article 2(f) and (g)).

31

The proceeds of crime are “any property derived from

or obtained, directly or indirectly, through the com-

mission of an offence”.

32

In most cases, conscation

requires a proven connection between the crime and

the property, which can be instrumentalities such as

vehicles, real property (factories and warehouses, for

example), contraband, offending substances like haz-

ardous chemicals or waste, or the proceeds or prots

related to a Crime that Affects the Environment. These

divestitures serve several goals. They may punish

an offender, act as a deterrent, disincentivize recid-

ivism, compensate victims, or support future enforce-

ment-related activities.

Deforestation and logging-related offences or illegal

deforestation and logging – Any person who engages

in forest clearing in violation of a Member State’s

legislative framework. It includes the illegal cutting,

burning, or destroying of forest trees and the illegal

digging or blasting of forests. Illegal logging is the

process of harvesting, processing, or transporting of

wood and derived products in violation of a Member

State’s legislative framework.

Fishing-related offences or illegal shing – This refers

to shing “conducted by national or foreign vessels

in waters under the jurisdiction of a State, without

the permission of that State, or in contravention of

its laws and regulations”, to shing “conducted by

vessels ying the ag of States that are parties to a

relevant regional sheries management organization

but operate in contravention of the conservation and

management measures adopted by that organization

and by which the States are bound, or relevant

provisions of the applicable international law”, as

well as to shing “in violation of national laws or

international obligations, including those undertaken

by cooperating States to a relevant regional sheries

management organization”.

33

Mining-related offences or illegal mining – Any person

who engages in any mining activity of a mineral re-

source (a) without lawful authority where such author-

ity is required by law; (b) without a relevant licence,

permit, certicate, or other legal permission granted

by the competent authorities; (c) by contravening the

conditions of said licence, permit, certicate, etc.; or

(d) in a manner that otherwise contravenes the rele-

vant legislation.

34

Legal person – Includes, but is not limited to, corporate

bodies, companies, rms, associations, societies, part-

nerships, local governments, trade unions, municipali-

ties, and public bodies.

35

Crimes that Affect

the Environment

2 3 4 51 The Landscape of

Criminalization

16

Liability of legal persons – The UNTOC requires States

parties to establish a legal framework addressing the

liability of legal persons for participation in serious

crimes involving an organized criminal group.

36

Part

2 of Article 10 species that liability for legal persons

may be criminal, civil or administrative and that two

or all of these approaches to liability may exist at the

same time. However, Article 10 (3) notes that such

liability must be without prejudice to the criminal

liability of natural persons involved in the offences.

“Civil liability refers to civil penalties imposed by

courts or similar bodies. Administrative liability is

generally associated with liability imposed by a

regulator, but in some legal systems judicial bodies

may also impose administrative penalties. Like civil

liability, administrative liability does not result in a

criminal conviction”.

37

Pollution-related offences – is the “indirect or direct

alteration of the biological, thermal, physical, or

radioactive properties of any medium in such a way

as to create a hazard or potential hazard to human

health or to the health, safety or welfare of any living

species”.

38

Restorative justice – “refers to a process for resolving

crime by focusing on redressing the harm done to

victims, holding offenders accountable for their

actions and, often also, engaging the community in

the resolution of the conict”.

39

Waste-related offences become waste crime when

any person engages in the trade, treatment, or dis-

posal of waste in ways that breach international or

domestic environmental legislation.

40

41

The working

denition here is broader than waste trafcking.

Wildlife-related offences become wildlife crime

when any person engages in exploitation of wildlife

in contravention of a Member State’s legislation. This

includes illegal wildlife trade

42

(“Any person who [in-

tentionally/with the requisite mental state] trafcs in

any specimen: (a) of a species listed in [national lists

and/or CITES]; (b) knowing that the specimen was tak-

en, possessed, distributed, transported, purchased or

sold in contravention of any national laws concerning

the protection or management of wild fauna or ora;

commits an offence”),

43

but also includes licence vio-

lations for hunting or harvesting as well as injurious

behaviours not linked to illegal trade (i.e., badger and

bear baiting).

Crimes that Affect

the Environment

2 3 4 51 The Landscape of

Criminalization

17

Each level of the pyramid provides some examples

of environmental legislation. The majority of environ-

mental legislation is at the national and sub-national

level. There are fewer international treaties and even

fewer regional treaties. The list of treaties is not ex-

haustive. The arrows indicate that some national leg-

islation exists to comply with membership in regional

and international agreements.

Figure 4 – Visual representation of the environmental legislation at different levels

REGIONAL

ENVIRON MENTAL

AGREEMENTS

Bamako Convention

(Africa);

Bern Convention (Europe);

Escazu Agreement

(LatinAmerica);

EU Waste Shipment Regulation (EU);

Waigani Convention (South Pacic)

INTERNATIONAL CONVENTIONS

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate

Change (UNFCCC); United Nations Convention on the

Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), Convention on Biological Diversity

(CBD), Convention on the International Trade in Endangered

Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), Convention on Migratory

Species (CMS); Convention on Long Range Air Pollution (CLRTAP),

Convention on the Prevention of Marine Pollution of Dumping Wastes

and Other Matter (London Convention), International Convention for the

Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL), Minamata Convention on Mercury,

Rotterdam Convention on the Prior Informed Consent Procedure for Certain

Hazardous Chemicals and Pesticides in International Trade, Stockholm Convention on

Persistent Organic Pollutants, Vienna Convention for the Protection of the Ozone Layer

(Montreal Protocol)

NATIONAL AND SUB-NATIONAL LEGISLATION

CLIMATE CHANGE POLLUTION AND WASTE

GENERAL ENVIRONMENT

BIODIVERSITY LOSS

Crimes that Affect

the Environment

2 3 4 51 The Landscape of

Criminalization

18

Methodology

This review presents the analysis of national environ-

mental legislation from all 193 UN Member States.

The review sought to answer: To what extent does the

environmental legislation of the 193 Member States

of the United Nations criminalize actions that harm

the environment? How are any such criminal offences

penalized, and does this conform to the denition of

serious crime set out in the UNTOC? The review ana-

lysed 2,502 pieces of environmental legislation in 193

countries, looking for provisions pertaining to criminal

offences related to deforestation and logging, mining,

air pollution, noise pollution, soil pollution, water pol-

lution, shing, waste, and wildlife, as dened in Box 2.

The breakdown of environmental legislation by crime

type is presented in Table 1, including the number of

countries where no legislation was identied. The legis-

lative review comprised desk-based research, content

analysis of the identied legislation, and inclusion of

Member State responses to a request for them to share

their legislation and related penalties (detailed below).

All relevant legislation that could be identied through

the ECOLEX and FAOLEX legislative databases, and

UNODC’s Sharing Electronic Resources and Laws on

Crime (SHERLOC) knowledge management portal for

each of the Member States was collated into a single

database.

44

Then, a request for information regarding

the accuracy of the legislation, the state of criminal-

ization and whether offences met the UNTOC deni-

tion of “serious crime” was sent to all Member States.

Thirty-two Member States responded to this request

with information, conrming or correcting the legisla-

tion and specifying whether violations of the legisla-

tion were administrative, civil, and or/criminal and what

the exact penalties were. Several Member States also

shared relevant completed court cases. Each piece of

all identied legislation was analysed. Unless submit-

ted by a Member State or referenced in the legislation,

the criminal legislation and penal codes were not re-

viewed; the focus was on the environmental legislation.

Twenty-three Member States responded with criminal

or penal codes to the request for information and thus

these were reviewed as part of the analysis. Open

source (automated) translation tools were used for

translation, when necessary, although not all legisla-

tion gathered could be translated. In these cases, or in

cases where the relevant legislation was not identied,

the data for that Member State in a particular category

was coded as “unknown” and is illustrated as “no data”

(see Figures 6 through 14). If at least one violation of

any of the legislation analysed for a Member State had

a criminal penalty, this was recorded in a master Excel

Spreadsheet as criminalization for that particular en-

vironmental area. Criminalization for each Crime that

Affects the Environment was broken down by “Crim-

inalized, not a serious crime”, “Criminalized, unknown

if a serious crime”, or “Criminalized, a serious crime”

referring to whether or not the penalty meets UNTOC’s

threshold of serious crime (see Figures 6 through 14).

In assessing whether a particular offence was crim-

inalized (the rst research question), a two-pronged

analysis was employed. First, an offence was coded

as criminalized if the Member State identied it as

criminalized or the legislation identied the offence

as one of a criminal nature. Second, if the criminal-

ization status was not explicit, offences were coded

as criminalized when accompanied by the possibility

of a custodial sentence. To answer the second re-

search question, crimes accompanied by a custodial

sentence meet the UNTOC serious crime denitional

threshold if the offence is punishable by a maximum

deprivation of liberty of at least four years or a more

serious penalty. As such, the legislation was analysed

to assess whether a possible custodial sentence for

any aspect of the offence could lead to at least four

years of imprisonment or other deprivation of liberty,

such as hard or forced labour. Typically, the severity

of the penalty depends upon the circumstances of the

offence, and legislation may not dene a particular,

singular penalty but rather a range that may ratchet

Crimes that Affect

the Environment

2 3 4 51 The Landscape of

Criminalization

19

up or down depending on aggravating or mitigating

circumstances. In general, across all Crimes that Af-

fect the Environment, offences causing greater injury

(e.g., large quantities of waste or pollution, trafcking

of endangered species (CITES-listed)), those that are

repeat offences, or offences committed by organized

crime groups are those that meet UNTOC’s denition

of serious crime. Examples of how national statutes

were considered in the classication of serious crime

include the following:

•

The statute states that the offence is subject to

a penalty of “1 to 5 years’ imprisonment.” Four

years is possible, so that was considered a “seri-

ous crime.”

• The statute states that the offence is subject to a

penalty of “1 to 5 years’ imprisonment and/or a ne

up to $50,000 USD.” This also was classied as

a “serious crime”; even though many people con-

victed under this provision may only receive a ne

(or a custodial sentence much shorter than four

years), four years’ imprisonment or more is possi-

ble/legally authorized.

• The statute says the offence is punishable by “up

to four years’ imprisonment.” This was also a “se-

rious crime.” The convention says, “at least four

years,” not “more than four years.”

• The statute says the offence is punishable by “1 to

3 years’ imprisonment.” That was not considered a

“serious crime.”

To identify whether legal persons may be held liable

under a particular law, the law was reviewed for an

explicit provision or the denition of “person” or any

other subject identied in the law. For the other data

categories, such as whether injunctive relief, cons-

cation, nes, or other alternative sanctions might be

available, the environmental legislation was reviewed,

and relevant provisions were identied and the form

of injunctive relief, the parameters of the conscation,

the amount of the nes, and the form of alternative

sanctions were recorded, with the data disaggregat-

ed into each of these categories. Other elements of

the analysis included whether within the environmen-

tal legislation there is the possibility of alternative or

restorative forms of punishments. The forms of alter-

native punishments, such as restoration of the envi-

ronment or compensation for environmental damage

among other possibilities were identied and again

recorded in their own separate column in the master

Excel Spreadsheet. It is important to note that for all

Member States additional legislation that was not

analysed here may contain relevant information. The

breakdown for each of the crimes along the criteria

outlined is provided below.

Table 1 – Breakdown of number of pieces of legislation that were analysed by environmental area across all

193 Member States

Environmental Area Number of Pieces of

Legislation

Number of Member States

where No Legislation was

Identied

Air pollution 258 14

Noise pollution 194 25

Soil pollution 241 29

Water pollution 296 0

Illegal deforestation and logging 294 6

Illegal mining 226 20

Illegal shing 304 1

Waste violations 267 8

Wildlife violations 472 0

Crimes that Affect

the Environment

2 3 4 51 The Landscape of

Criminalization

20

The Analysis

The state of criminalization

Most Member States across the nine environmental

areas considered in this analysis criminalize violations

of their legislation, though there is variation across the

nine environmental areas. Among these, violations of

legislation related to wildlife, waste, deforestation and

logging, along with air and water pollution offences

were most likely to include criminal offences (see Fig-

ure 1 in the Findings). The crimes for which the pen-

alties meet the UNTOC serious crime threshold in the

highest number of Member States are wildlife crime

and waste crime. These were followed closely by air

and water pollution (see Figure 3 in the Findings).

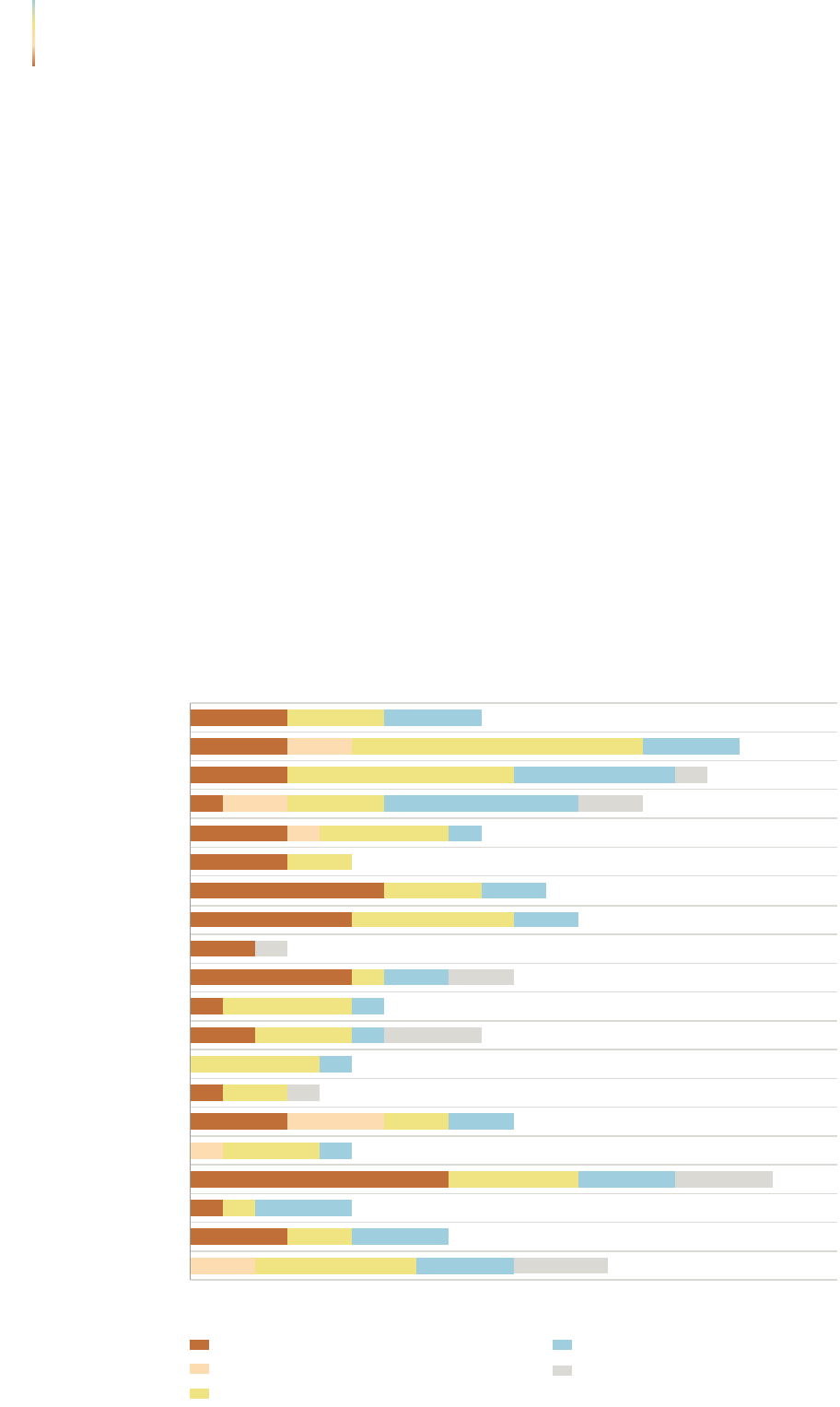

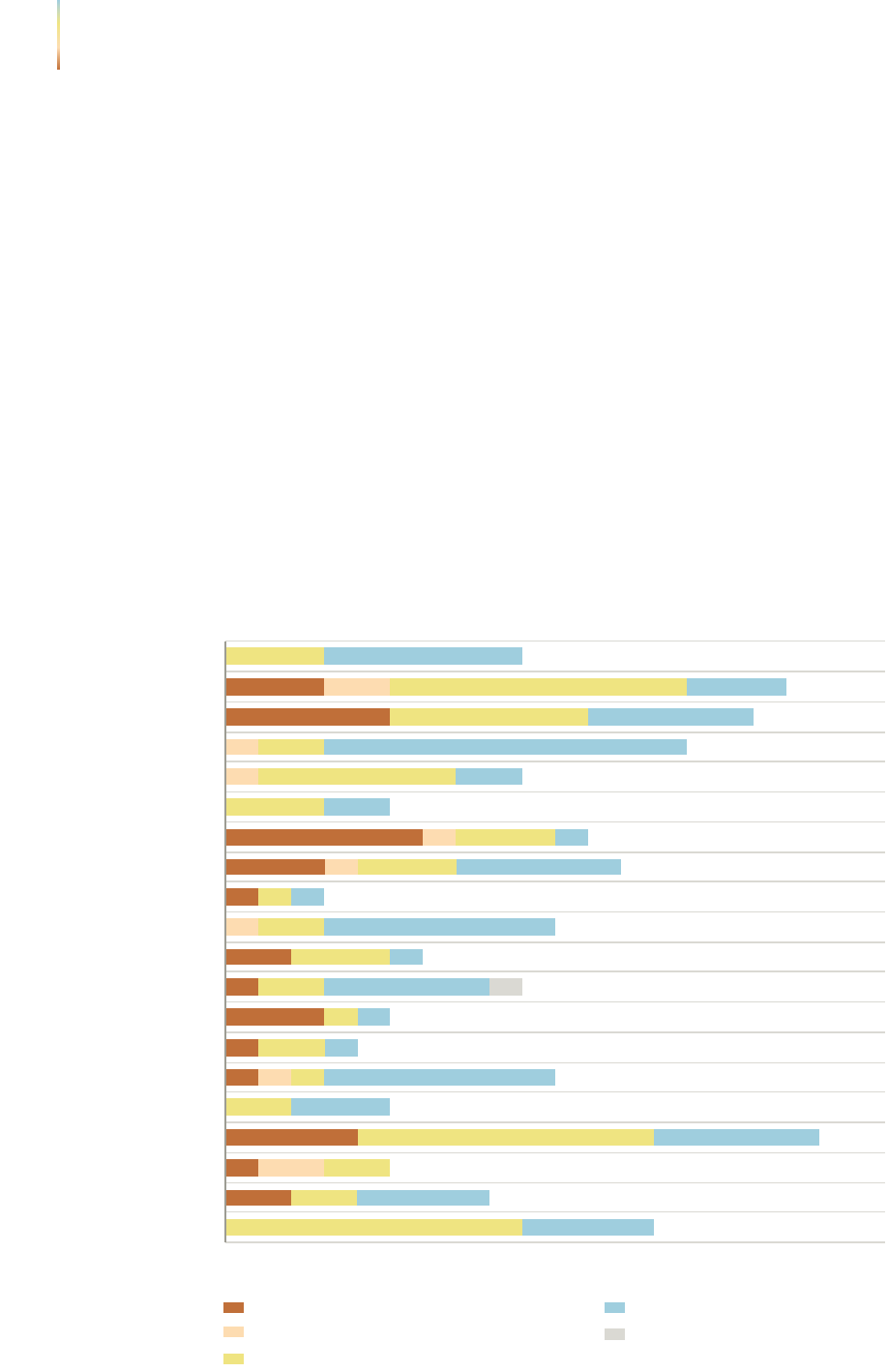

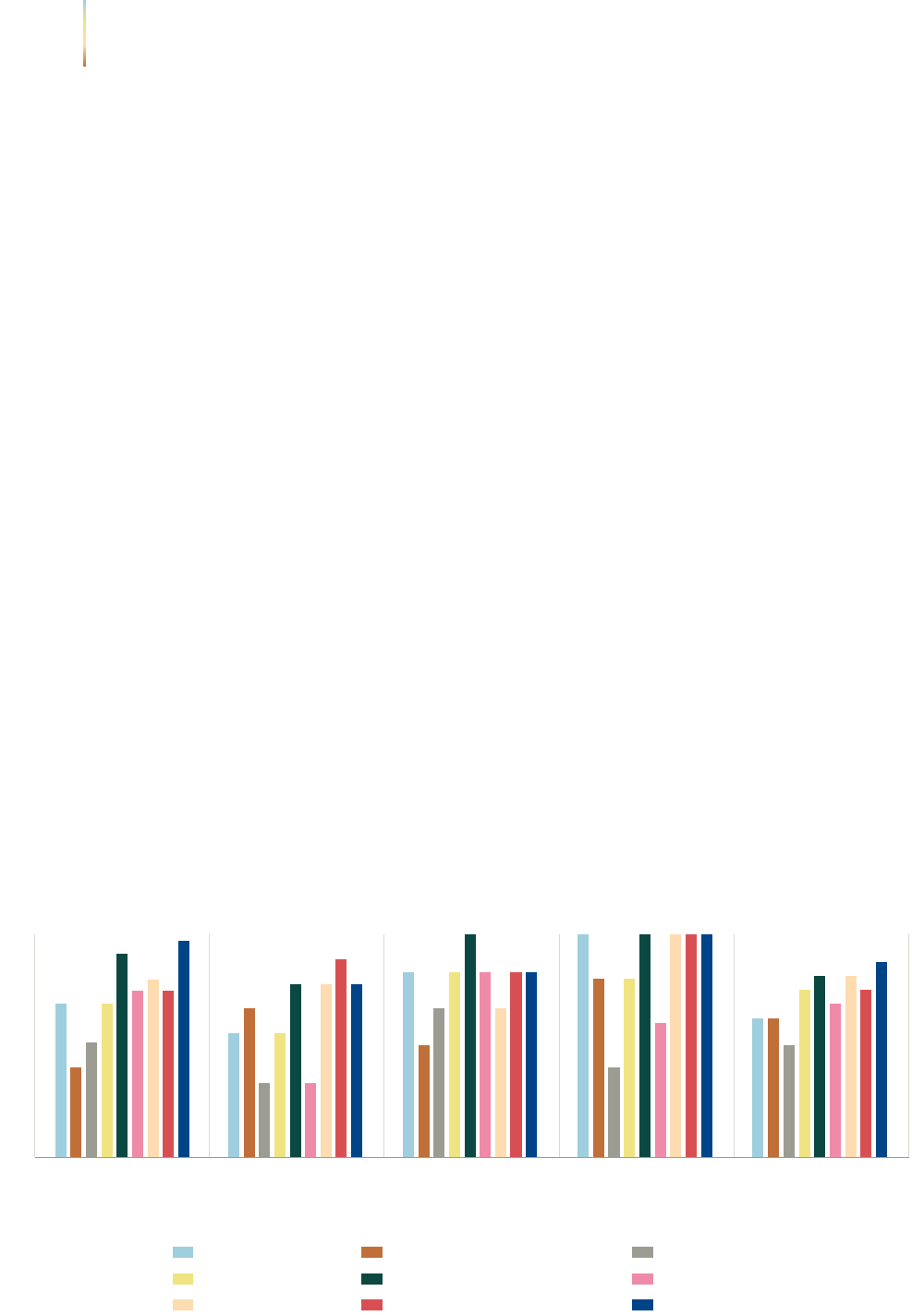

Legal vs natural persons

The environmental legislation was analysed for ex-

plicit reference to liability of legal persons. Violations

of waste legislation and air pollution most frequent-

ly provided the potential to hold legal persons liable

for offences. Noise and water pollution legislation

appears to lag in holding legal persons liable and

generally only appears to hold natural persons liable.

As noted, it is possible that liability of legal persons

is codied in other legislation not analysed here. In-

terestingly, while shing and forestry are very often

an industrial activity undertaken by corporate actors,

the relevant environmental legislation frequently pun-

ishes violations by legal persons less severely than

natural persons, which means the most common and

serious offenders are likely subjected to some of the

lowest levels of punishment.For example, out of the

118 countries with environmental legislation criminal-

izing illegal shing only 19 of these explicitly mention

the liability of legal persons.Figure 5 indicates the

number of Member States which have explicit penal-

ties for legal persons; the remaining Member States

may have provisions for legal persons in other legis-

lation, but for this analysis are considered unknown.

Other sanctions

Legislation that includes conscation provisions var-

ies across countries and environmental areas. Over-

all, conscation provisions do not appear common in

legislation pertaining to the environment; for exam-

ple, of the 193 Member States whose legislation was

reviewed for this analysis only 37 appear to provide

for conscation regarding water-related offences,

despite 135 criminalizing water pollution. Further,

it appears from the legislative review that it is more

common that conscation provisions apply to equip-

ment or objects (e.g., vehicles and wildlife products)

related to the crime rather than prots or proceeds,

particularly but not exclusively with respect to pol-

lution crimes. For environmental areas such as noise

pollution, equipment such as speakers and sirens may

be subject to conscation when the crime is not prot

motivated. In some cases, what may be “specialized”

conscation provisions exist to address the involve-

ment of high-risk substances, such as when ofcers

may seize and take into possession hazardous chem-

icals.

45

While provisions for conscation may not be

widely included in environmental legislation they may

still be included in general criminal or other legisla-

tion, thereby still providing conscation options for

law enforcement and the judiciary.

Whether offences are criminalized or not, civil reme-

dies that require compensation, restoration, or resti-

tution are a means of achieving justice in cases where

the commission of an offence harms people, wildlife,

or the environment. Although not common, examples

do exist where legislation gives the justice system

exibility to implement solutions to recover the costs

Crimes that Affect

the Environment

2 3 4 51 The Landscape of

Criminalization

21

of and restore the damage from environmental harms.

For example, legislation in one Member State provides

that an offender may be required to remove pollution,

install pollution-control equipment, cease release of

any harmful substance, and restore the environment

to its previous condition. Overall, only 35 Member

States require restoration for water pollution; a low-

er rate of restorative remedies than criminalization is

common across all categories under analysis, though

these provisions may exist in other legislative instru-

ments. Compensation may be required to pay back

costs for clean-up and/or to pay any victims suffer-

ing harm from damage to the environment. Such an

approach appears relatively common in the context

of soil pollution, where 24 Member States require

offenders to compensate injured parties. While noise

violations may cause harm that cannot necessarily be

remedied, law enforcement may pursue other types of

remedies, such as closure of facilities or installations,

contract bans or restrictions, or the requirement to

fund environmentally benecial projects.

Alternatives to nes and imprisonment are not as com-

mon as nancial and custodial sentences. As evident

below, the range and diversity of these most common

sanctions are extensive for each of the environmental

areas that were reviewed for this analysis.

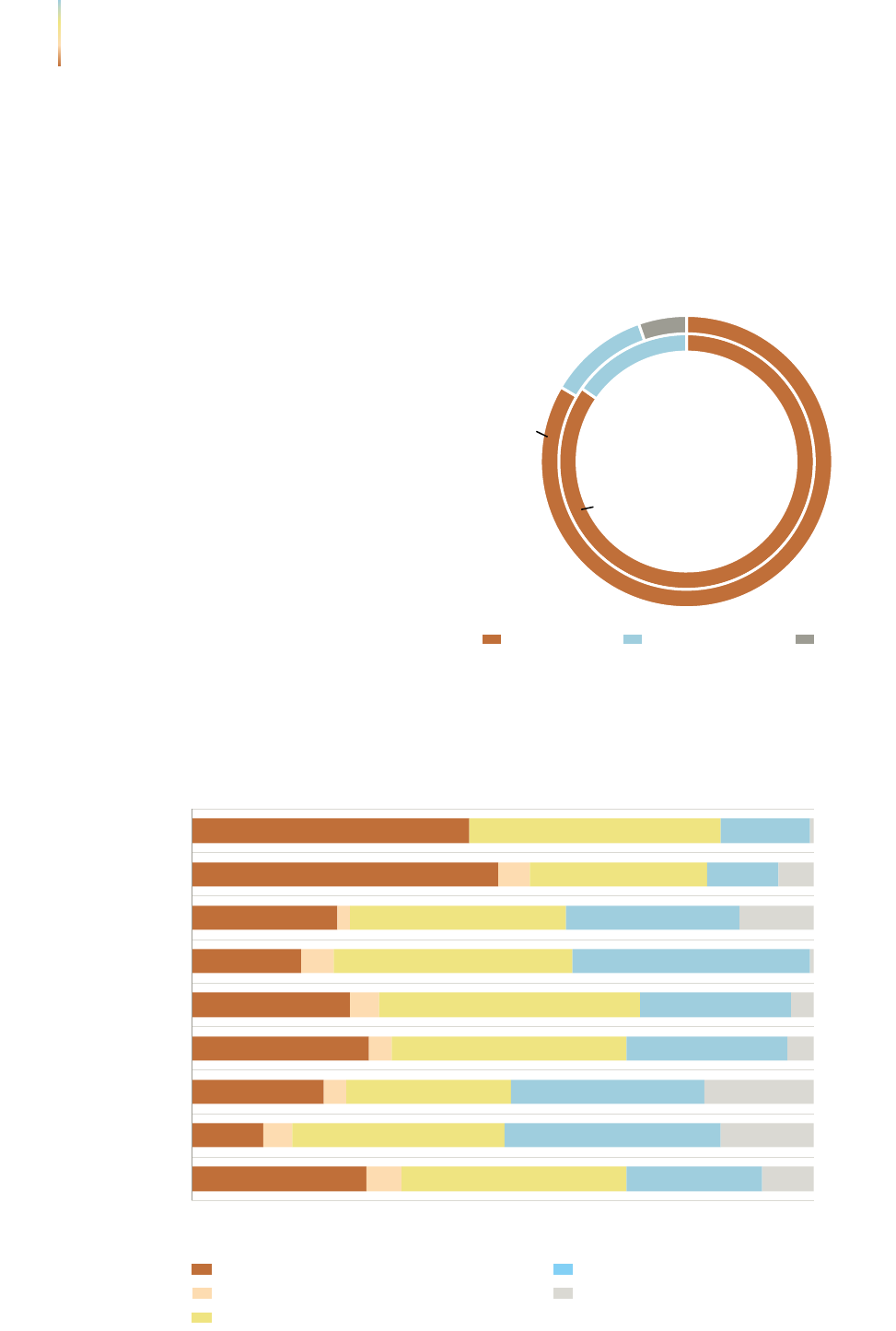

Figure 5 – Known Liability of Legal Persons*

* The liability of legal persons for wildlife crime was taken from the Member State responses to the Information Gathering Tool from CCPCJ

Resolution 31/1 as well as content analysis of Member States’ legislation.

Air pollution

Noise pollution

Soil pollution

Water pollution

Deforestation

and logging

Fishing

Mining

Waste

Wildlife

Environmental area

Number of Member States

0 20 40 60 80 100 120 140 160

146

104

20

19

121

76

89

120

69

Crimes that Affect

the Environment

2 3 4 51 The Landscape of

Criminalization

22

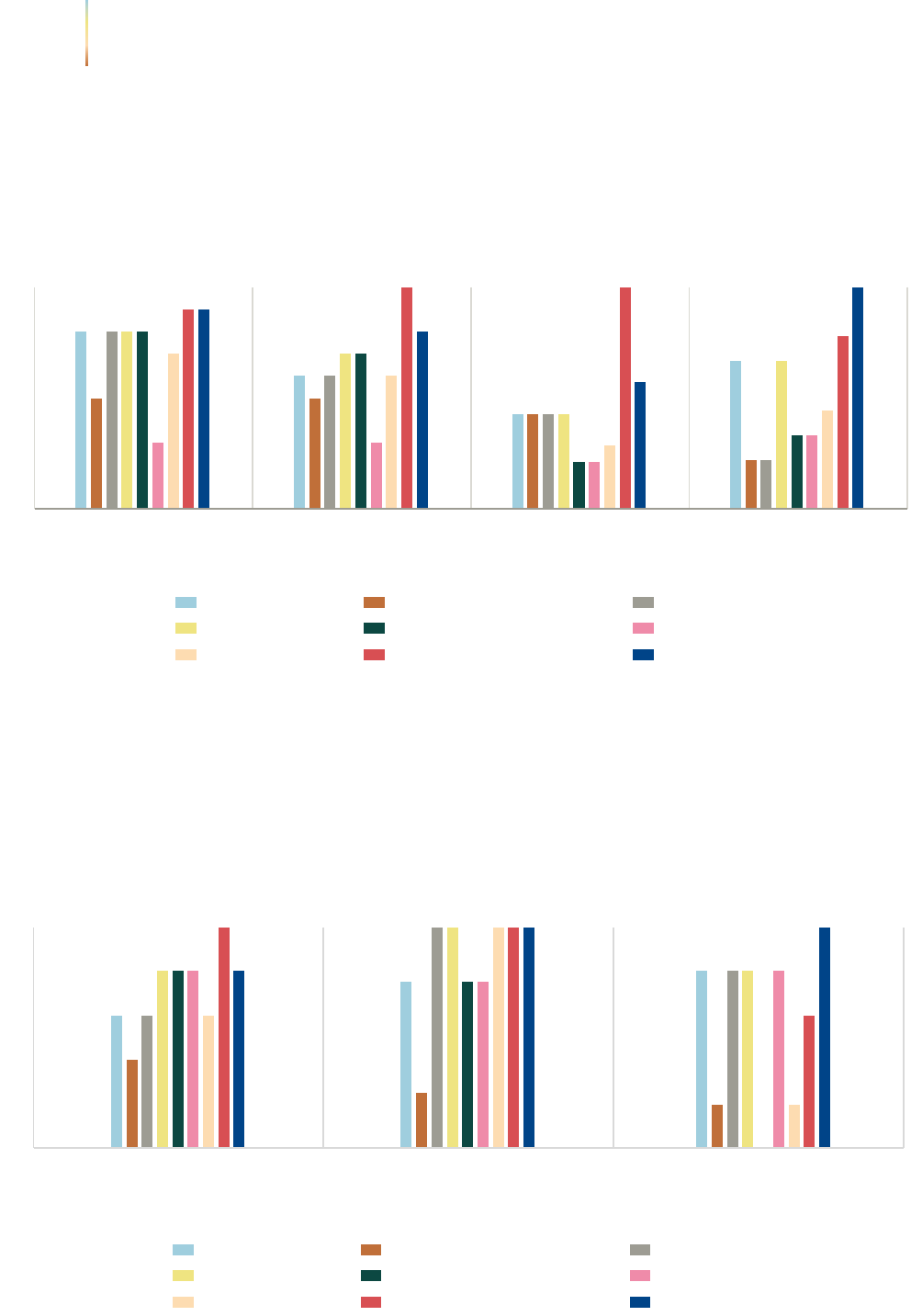

Deforestation and logging

The content analysis of deforestation and logging

legislation focused on the working denition in Box1

(illegal forest clearing through illegal cutting, burning,

and destruction etc.) and not on the illegal trade of

timber. The legislation of 139 Member States was

identied as criminalizing these activities, with 49 of

those having penalties that met the UNTOC denition

of a serious crime. The custodial penalties have a great

deal of variability with some prescribing incarceration

from 15 to 30 days while others prescribe up to 14

years depending on the type and severity of the

offence. Likewise, criminal nes ranged signicantly.

At the low end, nes are less than USD 500; at the

high end, nes could be tens of thousands of USD.

Often nes are calculated by penalty units determined

by the national minimum wage and, for this crime,

occasionally per tree.

Conscation of equipment, forest products, money

and other items was included in environmental legis-

lation and was only evident in 19 Member States. Res-

toration or restitution was more prevalent here per-

haps than in other environmental areas (24 Member

States). Sanctions also included loss of licence and

prohibition from logging for set periods of time. The

lack of criminalization of legal persons (in 20 Member

States) warrants further scrutiny since forestry is a

highly industrialized sector where corporations may

be the main perpetrators.

1826

1521

3112

11111

1

35

41

227

1

1

2

261

5214

51

24

4

1

3

1

4

23

8

211

121

2

22

1

6

1

3

2115

1

Caribbean

Central America

Central Asia

Eastern Africa

Eastern Asia

Eastern Europe

Melanesia

Micronesia

Middle Africa

Northern Africa

Northern Europe

Polynesia

South America

South-Eastern Asia

Southern Africa

Southern Asia

Southern Europe

Western Africa

Western Asia

Western Europe

Number of Member States

Sub- or intermediate region

No data

Not criminalized

Criminalized, not a serious crime

Criminalized, unknown if a serious crime

Criminalized, a serious crime

1

Figure 6 – State of criminalization of deforestation and logging-related offences

Crimes that Affect

the Environment

2 3 4 51 The Landscape of

Criminalization

23

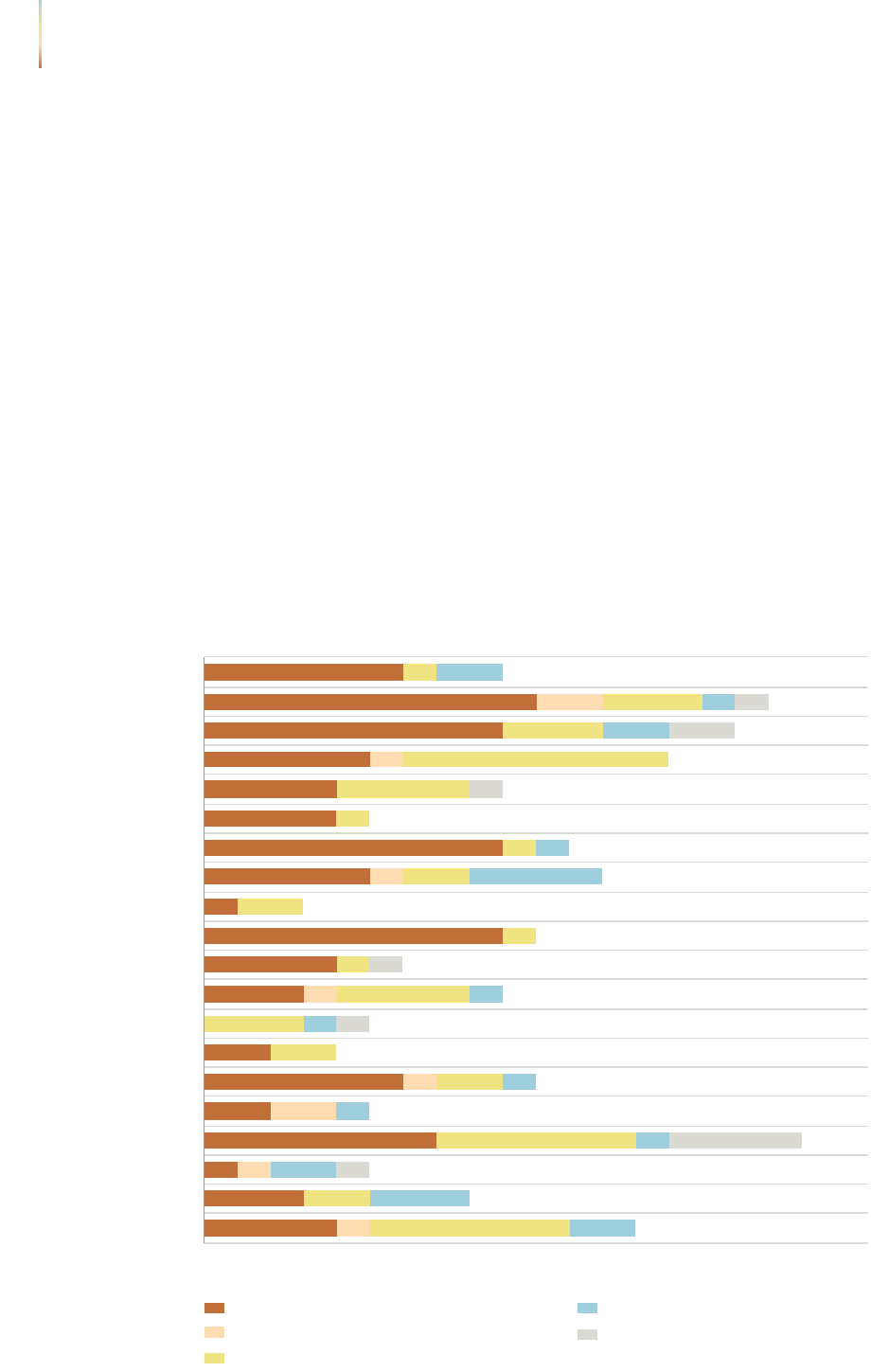

Mining

Violations of mining-related legislation constitute a

criminal offence in the environmental legislation of

116 Member States reviewed for this analysis, with

custodial sentences ranging in length from 15 days

to 20 years. A relatively high proportion of the custo-

dial penalties meet the UNTOC threshold of a serious

crime (45 Member States).

In addition to custodial sentences, Member States

have established a wide range of monetary nes in

relation to illegal mining. A few Member States differ-

entiate between natural and legal persons in the pro-

vision of monetary nes, like in other environmental

areas. More prominently than in the context of other

environmental areas, monetary nes for illegal mining

can double, triple, or even quintuple with repeated of-

fences. One Member State calculates the amount of

ne based upon the assets of the offender.

Caribbean

Number of Member States

Central America

Central Asia

Eastern Africa

Eastern Asia

Eastern Europe

Melanesia

Micronesia

Middle Africa

Northern Africa

Northern Europe

Polynesia

South America

South-Eastern Asia

Southern Africa

Southern Asia

Southern Europe

Western Africa

Western Asia

Western Europe

6

2

1

1

3

1

4

1

2

1

2

4

4

2

1

3

1

2

1

4

4

3

5

6

2

5

4

4

4

1

7

2

2

1

1

3

3

5

1

5

3

2

1

4

7

7

1

2

1

1

1

7

1

3

3

4

1

1

1

3

5

3

1

5

3

2

Sub- or intermediate region

No data

Not criminalized

Criminalized, not a serious crime

Criminalized, unknown if a serious crime

Criminalized, a serious crime

2

Figure 7 – State of criminalization of mining-related offences

Crimes that Affect

the Environment

2 3 4 51 The Landscape of

Criminalization

24

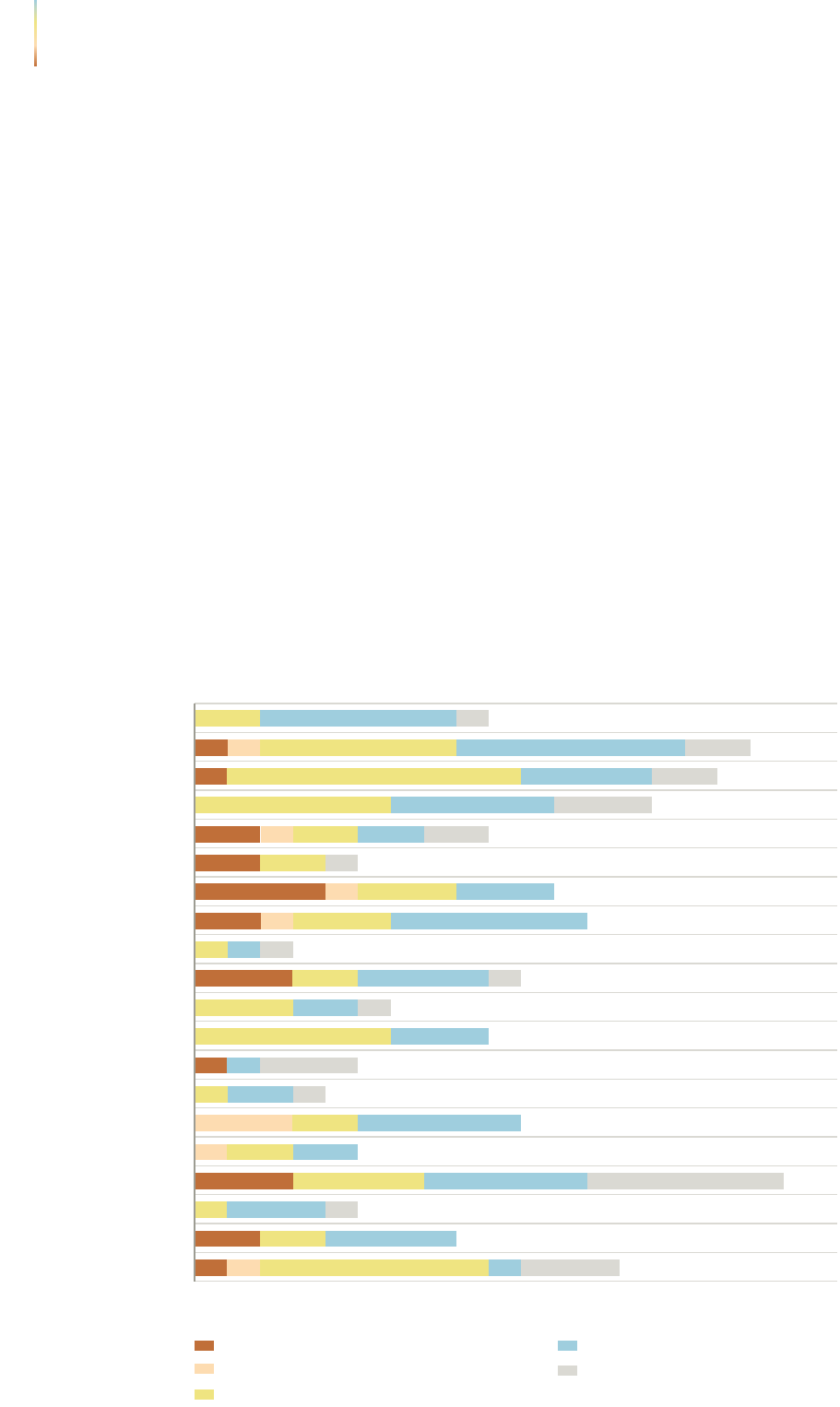

Pollution

Air pollution

The review of air pollution legislation for this analysis

reveals a trend toward criminalization of air pollution

offences but a lag in relevant criminal sanctions con-

stituting “serious crimes” as dened by UNTOC. Of the

193 Member States reviewed for this report, 135 crimi-

nalize air pollution offences. Forty per cent of these do

so in a way that meets the “serious crime” threshold.

The range of penalties among the nearly 70 per cent

of Member States that criminalize air pollution is vast,

from monetary nes to extensive custodial sentences,

including labour or correctional work as a type of cus-

todial penalty. The custodial sentences vary greatly,

from a day’s imprisonment at the very low end, to life

imprisonment at the other extreme. Member States

vary signicantly with respect to the degree of ex-

ibility concerning custodial sentences that can be

given for mitigating and aggravating circumstances

during sentencing.

Just over two-thirds (127 Member States) of the air

pollution legislation provides monetary nes for vio-

lations (some in addition to custodial sentences), but

both the means of calculating monetary sanctions and

the amount of the nes differ dramatically by country.

For example, some Member States penalize ongoing

violations with nes that are incurred at daily rates.

One Memtion to a base ne of up to USD 2,365. An-

other Member State levies up to about USD 729,735

per day for ongoing violations.

Number of Member States

3

3

1

3

2

1

2

1

3

3

3

3

1

2

1

1

1

2

2

2

1

6

5

3

3

5

2

1

4

3

2

2

4

3

4

1

5

3

2

4

3

7

9

3

2

1

3

1

2

2

3

1

8

3

1

2

1

5

2

5

6

3

3

1

3

3

3

Caribbean

Central America

Central Asia

Eastern Africa

Eastern Asia

Eastern Europe

Melanesia

Micronesia

Middle Africa

Northern Africa

Northern Europe

Polynesia

South America

South-Eastern Asia

Southern Africa

Southern Asia

Southern Europe

Western Africa

Western Asia

Western Europe

Sub- or intermediate region

No data

Not criminalized

Criminalized, not a serious crime

Criminalized, unknown if a serious crime

Criminalized, a serious crime

Figure 8 – State of criminalization of air pollution-related offences

Crimes that Affect

the Environment

2 3 4 51 The Landscape of

Criminalization

25

Legislation may also distinguish between natural and

legal persons to identify appropriate nes. For exam-

ple,legislation may assign lower nes for individual

violators as opposed to violations involving corpora-

tions. For example, one Member State imposes a pen-

alty ve times greater in cases involving legal persons

than in cases involving natural persons. Several na-

tions target legal entities by imposing monetary nes

on corporations while either leaving the individual un-

punished or imposing custodial and/or administrative

penalties on individuals involved in the violation.

Noise pollution

Of the 193 Member States reviewed for this analysis,

97 Member States criminalize noise pollution viola-

tions. Of those, just 22 have penalties that meet the

UNTOC serious crime threshold, the lowest number

of the analysis. Generally, prison sentences for noise

pollution offences are less common than in other

environmental areas. Sixty-eight Member States in-

corporate custodial penalties into their legal frame

-

works. The highest custodial penalties range from

6 to 15 years. The highest penalties appear to arise

when noise or vibration is considered a nuisance or

pollutant, as opposed to situations in which regula-

tion and violations derive from noise-specic legis-

lation. For example, one Member State’s legislation

provides that noise pollution may be a serious crime

that affects the environment when committed either

intentionally or negligently. The lower-end of custodi-

al sentences is two to ten days, across all legislation,

and these provisions tend to be found in noise-spe-

cic legislation.

As with regulating other forms of acts that harm the

environment, daily nes are a relatively prominent

Number of Member States

Caribbean

Central America

Central Asia

Eastern Africa

Eastern Asia

Eastern Europe

Melanesia

Micronesia

Middle Africa

Northern Africa

Northern Europe

Polynesia

South America

South-Eastern Asia

Southern Africa

Southern Asia

Southern Europe

Western Africa

Western Asia

Western Europe

3

1

6

1

3

1

1

1

1

2

2

2

1

1

4

3

5

2

5

2

1

3

2

4

1

6

3

2

4

7

6

7

2

1

4

2

2

1

6

3

2

1

3

3

2

2

9

6

2

1

1

3

1

1

1

1

1

2

3

1

3

2

4

2

2

356

1

1

Sub- or intermediate region

No data

Not criminalized

Criminalized, not a serious crime

Criminalized, unknown if a serious crime

Criminalized, a serious crime

Figure 9 – State of criminalization for noise pollution

Crimes that Affect

the Environment

2 3 4 51 The Landscape of

Criminalization

26

form of penalizing noise violations, and these range

greatly. As far as the difference between natural and

legal persons, several Member States impose higher

nes on corporations than individuals, with at least

a few Member States imposing penalties up to ten

times higher on legal persons. A few countries also

impose graduated penalties, levying nes proportion-

ate to the severity of the violation.

Soil pollution

Of the 193 Member States’ legislation reviewed, 99

criminalize soil pollution offences, with 41 of those

having penalties that meet UNTOC’s serious crime

threshold. Custodial sentences for soil pollution vio-

lations range from 6 days to up to 15 years across all

legislation. In 48 Member States, legal persons are

held liable within the environmental legislation ana-

lysed. Accountability measures for natural persons

include an array of custodial sentences, monetary

nes, as well as compensation, rehabilitation, and

restoration. Like in other contexts, some legislation

scales the length and severity of custodial sentences

differently for natural and legal persons, for example

with a 1-10-year penalty range for natural persons and

a 5-10-year penalty range for legal persons. In this re-

view, 76 Member States were identied as imposing

a monetary ne on soil-related offences, six of which

provided for greater nes for legal persons.

Number of Member States

Caribbean

Central America

Central Asia

Eastern Africa

Eastern Asia

Eastern Europe

Melanesia

Micronesia

Middle Africa

Northern Africa

Northern Europe

Polynesia

South America

South-Eastern Asia

Southern Africa

Southern Asia

Southern Europe

Western Africa

Western Asia

Western Europe

3

5

2

2

1

1

3

1

1

6

3

3

2

4

4

4

4

2

2

1

4

3

4

6

2

2

2

5

4

5

5

1

3

2

2

3

3

3

4

1

1

1

2

1

3

4

5

6

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

3

1

6

5

1

1

4

1

3

3

1

3

1

3

3

2

Sub- or intermediate region

No data

Not criminalized

Criminalized, not a serious crime

Criminalized, unknown if a serious crime

Criminalized, a serious crime

Figure 10 – State of criminalization for soil pollution

Crimes that Affect

the Environment

2 3 4 51 The Landscape of

Criminalization

27

Water pollution

At least 135 of 193 Member States criminalize water

pollution,with 117 providing for a custodial sentencing

option. Of those that provide for custodial sentences,

55 meet UNTOC’s serious crime threshold. Custodi-

al penalties range from three days to up to 20 years.

Across all of the types of legislation reviewed, a signif-

icant range exists as to how Member States structure

penalties. In some cases, only a single custodial sen-

tence option exists, such as 5-years’ imprisonment,

rather than a range. At least one Member State im-

poses a higher custodial sentence range specically

for corporate entity leaders.

Monetary penalties are common for water pollution of-

fences; at least 128 of the 135 Member States provide

for the imposition of nes, which can include speci-

cations as to how the nes might be used, such as

for compensation or rehabilitation. In other cases, pay-

ment for compensation or rehabilitation may be a sep-

arate enforcement option. For example, 56 Member

States require water polluters to compensate injured

parties and/or restore the environment, including re-

imbursing the State, for damage caused and the costs

of rehabilitation. The severity of monetary nes rang-

es greatly, and like in other contexts, some countries

increase nes for ongoing or longstanding violations.

Other ranges may be based on the environmental

risk: one Member State’s monetary nes differentiate

between water pollution that poses a specic threat

to human health and that which poses a threat to an

ecosystem.

Caribbean

Central America

Central Asia

Eastern Africa

Eastern Asia

Eastern Europe

Melanesia

Micronesia

Middle Africa

Northern Africa

Northern Europe

Polynesia

South America

South-Eastern Asia

Southern Africa

Southern Asia

Southern Europe

Western Africa

Western Asia

Western Europe

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

3

3

4

5

2

2

1

3

1

2

1

4

2

1

2

7

3

1

3

7

2

5

2

2

1

3

5

5

1

1

2

8

2

5

6

9

4

1

1

3

1

1

2

2

1

7

3

3

1

6

1

5

1

4

3

1

6

6

2

Number of Member States

Sub- or intermediate region

No data

Not criminalized

Criminalized, not a serious crime

Criminalized, unknown if a serious crime

Criminalized, a serious crime

Figure 11 – State of criminalization for water pollution

Crimes that Affect

the Environment

2 3 4 51 The Landscape of

Criminalization

28

Fishing-related offences

Violations of sheries laws are criminalized in 118

of 193 Member States. Fines for illegal shing vary

widely. Such nes are often calculated based on the

national minimum wage or daily units (a set daily rate)

and these vary from two minimum wages to 1,000

daily units. In 108 Member States, there are custodial

sentences ranging from one to seven days all the way

up to 12 to 20 years. Criminalization in most Member

States, however, tends not to meet the UNTOC thresh-

old for serious crime, with only 34 Member States ap-

pearing to have set custodial penalties for four years

or above.

Very little data are available regarding legal persons

in relation to illegal shing. Only 19 Member States in

this analysis clearly delineated criminal penalties for

legal persons; for the remaining 174 countries, this is

unknown. Some Member States clearly included pro-